I am in love with fairy tales and the mirrors they hold to everyday life. This is not escapism, but a preference to view brutal truths slightly disguised, in a world just the other side of this one.

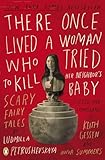

But even if you are married to verite-style fiction, and even if haven’t touched a fairy tale since your parents quit reading to you, you should grab There Once Lived A Woman Who Tried to Kill Her Neighbor’s Baby by Ludmilla Petrushevskaya.

But even if you are married to verite-style fiction, and even if haven’t touched a fairy tale since your parents quit reading to you, you should grab There Once Lived A Woman Who Tried to Kill Her Neighbor’s Baby by Ludmilla Petrushevskaya.

Petrushevskaya is a living, prolific, and now honored Russian writer. Theater provided an audience for her work when she couldn’t get her fiction into print, but by now she has become a champion of Russian letters, winning awards and receiving a nationwide birthday party when she turned seventy.

The early work that threatened Soviet officials was realistic in nature, according to the introduction by her translators, Keith Gessen and Anna Summers, who also write, “Her stories about the lives of Russian women were too dark, too direct, and too forbidding.”

There Once Lived A Woman Who Tried to Kill Her Neighbor’s Baby is subtitled “Scary Fairy Tales,” and some readers may find the stories dark and forbidding, if indirect. The fairy tales don’t bury the raw hardships of daily life that Petrushevskaya observed growing up in Moscow after WWII and throughout her life. Rather, the circumstances facing real people are the situations her characters also face, though slightly skewed. Sons are drafted and parents go to extremes to try to save their boys from service. Families divided by the military struggle to reunite. However, these facts reach the reader in dream-like forms, through post-apocalyptic landscapes that still bear recognizable emblems of Soviet life: close apartments, shared kitchens, and a simple hunger that is both literal and symbolic and drives people desperate for survival.

Petrushevskaya delivers these tales in simple sentences piled one on top of the other like a sturdy wall of concrete blocks. “Early in the war in Moscow there lived a woman named Lida. Her husband was a pilot, and she didn’t love him very much, but they got along well enough,” opens “Incident at Sokolniki.”

“There once lived a woman whose son hanged himself,” begins “The Miracle,” and what follows is not really a miracle, but a seeking of such from a near-dead drunk who trades favors for vodka.

“There once lived a woman who hated her neighbor – a single mother with a small child.” This is the first line of “Revenge,” the story that suggests the book’s title and draws portraits of two lonely women and the way their lives once feathered together, and how their friendship fell apart. The horror of the title, which never actually occurs in any story in the collection, is terrific and contributes suspense to the grim action reported.

If these stories are gray, blocky walls, the images, poetry and metaphor within them are beautiful, fluid cement that binds them. Shadows of ghosts hover around murderers. Characters break from tension and the ground shifts from the land of the living to the land of the dead, or from home to America. People trade money to bring their loved ones back to life. In some of the stories, the bribes work.

When people write about Ludmilla Petrushevskaya, they remark on the hope that clusters around the bleak stories. I am not so certain I read hope in these pages but there is redemption within them, something that keeps the fantastical and mystical events that do not often end happily from seeming ripe with despair. For me, maybe it is just the act of storytelling that is redemptive. Someone lived to tell the tale.