Once you have seen the astonishingly evocative portraits of the neo-Modernist painter Carl Köhler (1919-2006), you will wonder how he died relatively unknown outside of his native Sweden. Such are the vagaries of the art world: Andy Warhol‘s rather uninteresting 200 One Dollar Bills sells for over 40 million dollars, while the remarkable author portraits of Carl Köhler go all but unnoticed.

But this, perhaps, is changing. Thanks to the efforts of his son, Henry, Köhler’s work has made its way outside of Sweden for the first time. If you live in New York, you might have seen “Beyond the Words: The Author Portraits of Carl Köhler” at the Brooklyn Central Library this past winter and spring, or the write-up in The New York Times’ blog Paper Cuts. The show was also briefly at the Martin Luther King Jr. Library, in Washington, D.C., in July and August. Now, this exhibit is on its way to Canada: Its next stop is the Robarts Library at the University of Toronto (January-March 2010). After that, the show’s on to the University of British Columbia’s Irving K. Barber Learning Centre in Vancouver (April-June/July 2010). With any luck, these shows will not be the last.

While Köhler’s figure drawings from his time in Paris in the 1950’s are remarkable, as are his abstract figural paintings, it is what he called his “authorportraits,” his paintings of European and American writers, intellectuals, and popular artists that I am most taken with—as much for their content as for their formal diversity. These portraits comprise an astonishing variety of media and styles, a variety that reflects the variety of Köhler’s subjects, who included James Joyce, Günter Grass, Joyce Carol Oats, Michael Jackson, Simone de Beauvoir, and Fyodor Dostoyevsky, among many others. With the exception of a few Swedish artists, Köhler did not actually meet any of his subjects. His inspiration for his portraits came through each artist’s work. He was an avid reader of wide-ranging tastes and wrote himself, though he never published. Literature—and music and film—were his inspiration, but paint, ink, collage, and blockprint were his media.

While artists like R.B Kitaj and Don Bachardy have also produced significant collections of artist/author portraits, their own artistic styles remained relatively unchanged regardless of their artist subjects. Köhler’s experimentation with many startlingly different techniques and media in his portraiture, and his often exquisite pairings of style and subject, give his work an arresting and distinctive expressiveness. His portraits infuse the physiognomy of each artist’s face with the immaterial, spiritual dimension of his or her work and life. The authorportraits distill the essence of each artist—the mood and aesthetics of each artist’s work—with an uncanny, luminous intensity.

Köhler’s woodblock print of Franz Kafka, for instance, offers a disorienting, sinister labyrinth of lines whose sharp edges seem simultaneously to represent and dismantle the face of the artist. This vision of Kafka’s face is tenuous (a few more lines carved in the woodblock and the face would be unrecognizable) and this sense of human fragility suggested by the print echoes Kafka’s own. In works like The Metamorphosis or “Josephine the Singer (The Mouse Folk)”, Kafka asks us to see how delicate and vulnerable our lives and loves and societies are. This print’s black maze is also a vision of the byzantine, dehumanizing bureaucracy of a novel like The Trial, and a demonstration of metamorphosis: the longer you look at the portrait, the more it seems to represent the carapace of an insect, or a skull, or a snarled, unreadable web—all symbols of the Kafkaesque, with its the atmosphere of impending danger and death, its sense of menacing, disorienting complexity, of something becoming something else.

Köhler painted the American poet and novelist Charles Bukowski— uninhibited, antisocial spokesman for drinking, fighting, and fucking; defender of the inescapable squalor, oppressiveness, and futility of life—in an earthy, visceral red. The paint looks, appropriately, like dried, clotted blood. Bukowski was a poet of bodies and bodily hungers. His writings depict the dirty, lusty, ignoble side of human life and human nature and don’t apologize for their unsavory vision. Köhler’s rough, mottled, blood-colored paint communicates this essence precisely. The wound-like eyes and mouth of Köhler’s Bukowski—rough-gouged scars where the sensory organs ought to be—emphasize again the raw, brutal quality of Bukowski’s poetic vision, while the whole composition’s symmetry and balanced color palate suggest the lyricism of which Bukowski was also capable.

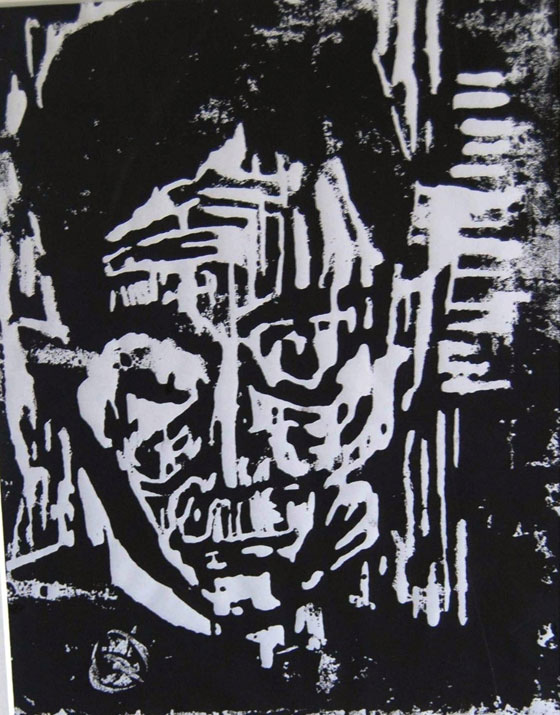

Henry Miller, the controversial and much demonized author of Tropic of Cancer, Tropic of Capricorn, and Black Spring, Köhler depicts “as Demon.” Using again the black and white block-print style of his Kafka, Köhler reassembles Miller’s rather benign facial features into a snarled, sinewy, black fist. Miller’s work is raw, uncomfortable stuff. I struggled with the apathy, squalor, and obscenity of Tropic of Cancer, and even the admiring can be a little circumspect about his work: George Orwell, ultimately Miller’s champion, described him as, “a completely negative, unconstructive, amoral writer, a mere Jonah, a passive acceptor of evil, a sort of Whitman among the corpses.” Köhler’s distortion of Miller’s face befits his work’s darkness, its difficulty, its simultaneously arresting and repellent frankness.

In contrast to Andy Warhol’s iconic images of Monroe, whose garish colors and tiled formats offer the actress as a celebrity brand, as something both less and more than human, Köhler’s portrait, with its delicate, wash-out palate and deconstructed, barely recognizable features, draws attention to the artifice and constructedness of Monroe’s celebrity. Köhler’s portrait is the inverse, the negative, of Warhol’s: it captures the troubled, shy, stuttering Monroe—the fragile private self that her celebrity obscured.

In this photo-collage, Michael Jackson‘s face looks as if it is made of porcelain, as if it is a doll’s face—but a doll’s face that has been vandalized or inexpertly drawn. The lips, eyebrows, and nostrils are, deliberately, not quite right. Köhler’s altered photo and the collage technique emphasize Jackson’s physical freakishness, which became the outward sign of his freakish personal life. The toy-like quality of the face also connotes Jackson’s obsession with childhood, while the doll face’s troublingly irregular features—somewhat suggestive of Heath Ledger‘s Joker make-up—recall his brutal childhood and his questionable interest in children.

The portrait and it’s title borrow something from surrealist painting (Think of Magritte‘s The Treachery of Images, sometimes known as Ceci n’est pas une pipe./This is not a pipe.) Köhler’s technique here forces the viewer into a kind of blindness, an approximation of Joyce’s failing sight.

Köhler’s portrait of Fyodor Doestoyevsky gives the author’s profile an otherworldly incandescence and suggests itself as perhaps inflected by the redemption plot of Crime and Punishment.

There are more images of Köhler’s work at the official website.

All images © Carl Köhler.