Mentioned in:

Most Anticipated: The Great Spring 2024 Preview

April

April 2

Women! In! Peril! by Jessie Ren Marshall [F]

For starters, excellent title. This debut short story collection from playwright Marshall spans sex bots and space colonists, wives and divorcées, prodding at the many meanings of womanhood. Short story master Deesha Philyaw, also taken by the book's title, calls this one "incisive! Provocative! And utterly satisfying!" —Sophia M. Stewart

The Audacity by Ryan Chapman [F]

This sophomore effort, after the darkly sublime absurdity of Riots I have Known, trades in the prison industrial complex for the Silicon Valley scam. Chapman has a sharp eye and a sharper wit, and a book billed as a "bracing satire about the implosion of a Theranos-like company, a collapsing marriage, and a billionaires’ 'philanthropy summit'" promises some good, hard laughs—however bitter they may be—at the expense of the über-rich. —John H. Maher

The Obscene Bird of Night by José Donoso, tr. Leonard Mades [F]

I first learned about this book from an essay in this publication by Zachary Issenberg, who alternatively calls it Donoso's "masterpiece," "a perfect novel," and "the crowning achievement of the gothic horror genre." He recommends going into the book without knowing too much, but describes it as "a story assembled from the gossip of society’s highs and lows, which revolves and blurs into a series of interlinked nightmares in which people lose their memory, their sex, or even their literal organs." —SMS

Globetrotting ed. Duncan Minshull [NF]

I'm a big walker, so I won't be able to resist this assemblage of 50 writers—including Edith Wharton, Katharine Mansfield, Helen Garner, and D.H. Lawrence—recounting their various journeys by foot, edited by Minshull, the noted walker-writer-anthologist behind The Vintage Book of Walking (2000) and Where My Feet Fall (2022). —SMS

All Things Are Too Small by Becca Rothfeld [NF]

Hieronymus Bosch, eat your heart out! The debut book from Rothfeld, nonfiction book critic at the Washington Post, celebrates our appetite for excess in all its material, erotic, and gluttonous glory. Covering such disparate subjects from decluttering to David Cronenberg, Rothfeld looks at the dire cultural—and personal—consequences that come with adopting a minimalist sensibility and denying ourselves pleasure. —Daniella Fishman

A Good Happy Girl by Marissa Higgins [F]

Higgins, a regular contributor here at The Millions, debuts with a novel of a young woman who is drawn into an intense and all-consuming emotional and sexual relationship with a married lesbian couple. Halle Butler heaps on the praise for this one: “Sometimes I could not believe how easily this book moved from gross-out sadism into genuine sympathy. Totally surprising, totally compelling. I loved it.” —SMS

City Limits by Megan Kimble [NF]

As a Los Angeleno who is steadily working my way through The Power Broker, this in-depth investigation into the nation's freeways really calls to me. (Did you know Robert Moses couldn't drive?) Kimble channels Caro by locating the human drama behind freeways and failures of urban planning. —SMS

We Loved It All by Lydia Millet [NF]

Planet Earth is a pretty awesome place to be a human, with its beaches and mountains, sunsets and birdsong, creatures great and small. Millet, a creative director at the Center for Biological Diversity in Tucson, infuses her novels with climate grief and cautions against extinction, and in this nonfiction meditation, she makes a case for a more harmonious coexistence between our species and everybody else in the natural world. If a nostalgic note of “Auld Lang Syne” trembles in Millet’s title, her personal anecdotes and public examples call for meaningful environmental action from local to global levels. —Nathalie op de Beeck

Like Love by Maggie Nelson [NF]

The new book from Nelson, one of the most towering public intellectuals alive today, collects 20 years of her work—including essays, profiles, and reviews—that cover disparate subjects, from Prince and Kara Walker to motherhood and queerness. For my fellow Bluets heads, this will be essential reading. —SMS

Traces of Enayat by Iman Mersal, tr. Robin Moger [NF]

Mersal, one of the preeminent poets of the Arabic-speaking world, recovers the life, work, and legacy of the late Egyptian writer Enayat al-Zayyat in this biographical detective story. Mapping the psyche of al-Zayyat, who died by suicide in 1963, alongside her own, Mersal blends literary mystery and memoir to produce a wholly original portrait of two women writers. —SMS

The Letters of Emily Dickinson ed. Cristanne Miller and Domhnall Mitchell [NF]

The letters of Emily Dickinson, one of the greatest and most beguiling of American poets, are collected here for the first time in nearly 60 years. Her correspondence not only gives access to her inner life and social world, but reveal her to be quite the prose stylist. "In these letters," says Jericho Brown, "we see the life of a genius unfold." Essential reading for any Dickinson fan. —SMS

April 9

Short War by Lily Meyer [F]

The debut novel from Meyer, a critic and translator, reckons with the United States' political intervention in South America through the stories of two generations: a young couple who meet in 1970s Santiago, and their American-born child spending a semester Buenos Aires. Meyer is a sharp writer and thinker, and a great translator from the Spanish; I'm looking forward to her fiction debut. —SMS

There's Going to Be Trouble by Jen Silverman [F]

Silverman's third novel spins a tale of an American woman named Minnow who is drawn into a love affair with a radical French activist—a romance that, unbeknown to her, mirrors a relationship her own draft-dodging father had against the backdrop of the student movements of the 1960s. Teasing out the intersections of passion and politics, There's Going to Be Trouble is "juicy and spirited" and "crackling with excitement," per Jami Attenberg. —SMS

Table for One by Yun Ko-eun, tr. Lizzie Buehler [F]

I thoroughly enjoyed Yun Ko-eun's 2020 eco-thriller The Disaster Tourist, also translated by Buehler, so I'm excited for her new story collection, which promises her characteristic blend of mundanity and surrealism, all in the name of probing—and poking fun—at the isolation and inanity of modern urban life. —SMS

Playboy by Constance Debré, tr. Holly James [NF]

The prequel to the much-lauded Love Me Tender, and the first volume in Debré's autobiographical trilogy, Playboy's incisive vignettes explore the author's decision to abandon her marriage and career and pursue the precarious life of a writer, which she once told Chris Kraus was "a bit like Saint Augustine and his conversion." Virginie Despentes is a fan, so I'll be checking this out. —SMS

Native Nations by Kathleen DuVal [NF]

DuVal's sweeping history of Indigenous North America spans a millennium, beginning with the ancient cities that once covered the continent and ending with Native Americans' continued fight for sovereignty. A study of power, violence, and self-governance, Native Nations is an exciting contribution to a new canon of North American history from an Indigenous perspective, perfect for fans of Ned Blackhawk's The Rediscovery of America. —SMS

Personal Score by Ellen van Neerven [NF]

I’ve always been interested in books that drill down on a specific topic in such a way that we also learn something unexpected about the world around us. Australian writer Van Neerven's sports memoir is so much more than that, as they explore the relationship between sports and race, gender, and sexuality—as well as the paradox of playing a colonialist sport on Indigenous lands. Two Dollar Radio, which is renowned for its edgy list, is publishing this book, so I know it’s going to blow my mind. —Claire Kirch

April 16

The Notebooks of Sonny Rollins by Sonny Rollins [NF]

The musings, recollections, and drawings of jazz legend Sonny Rollins are collected in this compilation of his precious notebooks, which he began keeping in 1959, the start of what would become known as his “Bridge Years,” during which he would practice at all hours on the Williamsburg Bridge. Rollins chronicles everything from his daily routine to reflections on music theory and the philosophical underpinnings of his artistry. An indispensable look into the mind and interior life of one of the most celebrated jazz musicians of all time. —DF

Henry Henry by Allen Bratton [F]

Bratton’s ambitious debut reboots Shakespeare’s Henriad, landing Hal Lancaster, who’s in line to be the 17th Duke of Lancaster, in the alcohol-fueled queer party scene of 2014 London. Hal’s identity as a gay man complicates his aristocratic lineage, and his dalliances with over-the-hill actor Jack Falstaff and promising romance with one Harry Percy, who shares a name with history’s Hotspur, will have English majors keeping score. Don’t expect a rom-com, though. Hal’s fraught relationship with his sexually abusive father, and the fates of two previous gay men from the House of Lancaster, lend gravity to this Bard-inspired take. —NodB

Bitter Water Opera by Nicolette Polek [F]

Graywolf always publishes books that make me gasp in awe and this debut novel, by the author of the entrancing 2020 story collection Imaginary Museums, sounds like it’s going to keep me awake at night as well. It’s a tale about a young woman who’s lost her way and writes a letter to a long-dead ballet dancer—who then visits her, and sets off a string of strange occurrences. —CK

Norma by Sarah Mintz [F]

Mintz's debut novel follows the titular widow as she enjoys her newfound freedom by diving headfirst into her surrounds, both IRL and online. Justin Taylor says, "Three days ago I didn’t know Sarah Mintz existed; now I want to know where the hell she’s been all my reading life. (Canada, apparently.)" —SMS

What Kingdom by Fine Gråbøl, tr. Martin Aitken [F]

A woman in a psychiatric ward dreams of "furniture flickering to life," a "chair that greets you," a "bookshelf that can be thrown on like an apron." This sounds like the moving answer to the otherwise puzzling question, "What if the Kantian concept of ding an sich were a novel?" —JHM

Weird Black Girls by Elwin Cotman [F]

Cotman, the author of three prior collections of speculative short stories, mines the anxieties of Black life across these seven tales, each of them packed with pop culture references and supernatural conceits. Kelly Link calls Cotman's writing "a tonic to ward off drabness and despair." —SMS

Presence by Tracy Cochran [NF]

Last year marked my first earnest attempt at learning to live more mindfully in my day-to-day, so I was thrilled when this book serendipitously found its way into my hands. Cochran, a New York-based meditation teacher and Tibetan Buddhist practitioner of 50 years, delivers 20 psycho-biographical chapters on recognizing the importance of the present, no matter how mundane, frustrating, or fortuitous—because ultimately, she says, the present is all we have. —DF

Committed by Suzanne Scanlon [NF]

Scanlon's memoir uses her own experience of mental illness to explore the enduring trope of the "madwoman," mining the work of Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Virginia Woolf, Sylvia Plath, Audre Lorde, and others for insights into the long literary tradition of women in psychological distress. The blurbers for this one immediately caught my eye, among them Natasha Trethewey, Amina Cain, and Clancy Martin, who compares Scanlon's work here to that of Marguerite Duras. —SMS

Unrooted by Erin Zimmerman [NF]

This science memoir explores Zimmerman's journey to botany, a now endangered field. Interwoven with Zimmerman's experiences as a student and a mother is an impassioned argument for botany's continued relevance and importance against the backdrop of climate change—a perfect read for gardeners, plant lovers, or anyone with an affinity for the natural world. —SMS

April 23

Reboot by Justin Taylor [F]

Extremely online novels, as a rule, have become tiresome. But Taylor has long had a keen eye for subcultural quirks, so it's no surprise that PW's Alan Scherstuhl says that "reading it actually feels like tapping into the internet’s best celeb gossip, fiercest fandom outrages, and wildest conspiratorial rabbit holes." If that's not a recommendation for the Book Twitter–brained reader in you, what is? —JHM

Divided Island by Daniela Tarazona, tr. Lizzie Davis and Kevin Gerry Dunn [F]

A story of multiple personalities and grief in fragments would be an easy sell even without this nod from Álvaro Enrigue: "I don't think that there is now, in Mexico, a literary mind more original than Daniela Tarazona's." More original than Mario Bellatin, or Cristina Rivera Garza? This we've gotta see. —JHM

Prairie, Dresses, Art, Other by Danielle Dutton [NF]

Coffee House Press has for years relished its reputation for publishing “experimental” literature, and this collection of short stories and essays about literature and art and the strangeness of our world is right up there with the rest of Coffee House’s edgiest releases. Don’t be fooled by the simple cover art—Dutton’s work is always formally inventive, refreshingly ambitious, and totally brilliant. —CK

I Just Keep Talking by Nell Irvin Painter [NF]

I first encountered Nell Irvin Painter in graduate school, as I hung out with some Americanists who were her students. Painter was always a dazzling, larger-than-life figure, who just exuded power and brilliance. I am so excited to read this collection of her essays on history, literature, and politics, and how they all intersect. The fact that this collection contains Painter’s artwork is a big bonus. —CK

April 30

Real Americans by Rachel Khong [F]

The latest novel from Khong, the author of Goodbye, Vitamin, explores class dynamics and the illusory American Dream across generations. It starts out with a love affair between an impoverished Chinese American woman from an immigrant family and an East Coast elite from a wealthy family, before moving us along 21 years: 15-year-old Nick knows that his single mother is hiding something that has to do with his biological father and thus, his identity. C Pam Zhang deems this "a book of rare charm," and Andrew Sean Greer calls it "gorgeous, heartfelt, soaring, philosophical and deft." —CK

The Swans of Harlem by Karen Valby [NF]

Huge thanks to Bebe Neuwirth for putting this book on my radar (she calls it "fantastic") with additional gratitude to Margo Jefferson for sealing the deal (she calls it "riveting"). Valby's group biography of five Black ballerinas who forever transformed the art form at the height of the Civil Rights movement uncovers the rich and hidden history of Black ballet, spotlighting the trailblazers who paved the way for the Misty Copelands of the world. —SMS

Appreciation Post by Tara Ward [NF]

Art historian Ward writes toward an art history of Instagram in Appreciation Post, which posits that the app has profoundly shifted our long-established ways of interacting with images. Packed with cultural critique and close reading, the book synthesizes art history, gender studies, and media studies to illuminate the outsize role that images play in all of our lives. —SMS

May

May 7

Bad Seed by Gabriel Carle, tr. Heather Houde [F]

Carle’s English-language debut contains echoes of Denis Johnson’s Jesus’s Son and Mariana Enriquez’s gritty short fiction. This story collection haunting but cheeky, grim but hopeful: a student with HIV tries to avoid temptation while working at a bathhouse; an inebriated friend group witnesses San Juan go up in literal flames; a sexually unfulfilled teen drowns out their impulses by binging TV shows. Puerto Rican writer Luis Negrón calls this “an extraordinary literary debut.” —Liv Albright

The Lady Waiting by Magdalena Zyzak [F]

Zyzak’s sophomore novel is a nail-biting delight. When Viva, a young Polish émigré, has a chance encounter with an enigmatic gallerist named Bobby, Viva’s life takes a cinematic turn. Turns out, Bobby and her husband have a hidden agenda—they plan to steal a Vermeer, with Viva as their accomplice. Further complicating things is the inevitable love triangle that develops among them. Victor LaValle calls this “a superb accomplishment," and Percival Everett says, "This novel pops—cosmopolitan, sexy, and funny." —LA

América del Norte by Nicolás Medina Mora [F]

Pitched as a novel that "blends the Latin American traditions of Roberto Bolaño and Fernanda Melchor with the autofiction of U.S. writers like Ben Lerner and Teju Cole," Mora's debut follows a young member of the Mexican elite as he wrestles with questions of race, politics, geography, and immigration. n+1 co-editor Marco Roth calls Mora "the voice of the NAFTA generation, and much more." —SMS

How It Works Out by Myriam Lacroix [F]

LaCroix's debut novel is the latest in a strong early slate of novels for the Overlook Press in 2024, and follows a lesbian couple as their relationship falls to pieces across a number of possible realities. The increasingly fascinating and troubling potentialities—B-list feminist celebrity, toxic employer-employee tryst, adopting a street urchin, cannibalism as relationship cure—form a compelling image of a complex relationship in multiversal hypotheticals. —JHM

Cinema Love by Jiaming Tang [F]

Ting's debut novel, which spans two continents and three timelines, follows two gay men in rural China—and, later, New York City's Chinatown—who frequent the Workers' Cinema, a movie theater where queer men cruise for love. Robert Jones, Jr. praises this one as "the unforgettable work of a patient master," and Jessamine Chan calls it "not just an extraordinary debut, but a future classic." —SMS

First Love by Lilly Dancyger [NF]

Dancyger's essay collection explores the platonic romances that bloom between female friends, giving those bonds the love-story treatment they deserve. Centering each essay around a formative female friendship, and drawing on everything from Anaïs Nin and Sylvia Plath to the "sad girls" of Tumblr, Dancyger probes the myriad meanings and iterations of friendship, love, and womanhood. —SMS

See Loss See Also Love by Yukiko Tominaga [F]

In this impassioned debut, we follow Kyoko, freshly widowed and left to raise her son alone. Through four vignettes, Kyoko must decide how to raise her multiracial son, whether to remarry or stay husbandless, and how to deal with life in the face of loss. Weike Wang describes this one as “imbued with a wealth of wisdom, exploring the languages of love and family.” —DF

The Novices of Lerna by Ángel Bonomini, tr. Jordan Landsman [F]

The Novices of Lerna is Landsman's translation debut, and what a way to start out: with a work by an Argentine writer in the tradition of Jorge Luis Borges and Adolfo Bioy Casares whose work has never been translated into English. Judging by the opening of this short story, also translated by Landsman, Bonomini's novel of a mysterious fellowship at a Swiss university populated by doppelgängers of the protagonist is unlikely to disappoint. —JHM

Black Meme by Legacy Russell [NF]

Russell, best known for her hit manifesto Glitch Feminism, maps Black visual culture in her latest. Black Meme traces the history of Black imagery from 1900 to the present, from the photograph of Emmett Till published in JET magazine to the footage of Rodney King's beating at the hands of the LAPD, which Russell calls the first viral video. Per Margo Jefferson, "You will be galvanized by Legacy Russell’s analytic brilliance and visceral eloquence." —SMS

The Eighth Moon by Jennifer Kabat [NF]

Kabat's debut memoir unearths the history of the small Catskills town to which she relocated in 2005. The site of a 19th-century rural populist uprising, and now home to a colorful cast of characters, the Appalachian community becomes a lens through which Kabat explores political, economic, and ecological issues, mining the archives and the work of such writers as Adrienne Rich and Elizabeth Hardwick along the way. —SMS

Stories from the Center of the World ed. Jordan Elgrably [F]

Many in America hold onto broad, centuries-old misunderstandings of Arab and Muslim life and politics that continue to harm, through both policy and rhetoric, a perpetually embattled and endangered region. With luck, these 25 tales by writers of Middle Eastern and North African origin might open hearts and minds alike. —JHM

An Encyclopedia of Gardening for Colored Children by Jamaica Kincaid and Kara Walker [NF]

Two of the most brilliant minds on the planet—writer Jamaica Kincaid and visual artist Kara Walker—have teamed up! On a book! About plants! A dream come true. Details on this slim volume are scant—see for yourself—but I'm counting down the minutes till I can read it all the same. —SMS

Physics of Sorrow by Georgi Gospodinov, tr. Angela Rodel [F]

I'll be honest: I would pick up this book—by the International Booker Prize–winning author of Time Shelter—for the title alone. But also, the book is billed as a deeply personal meditation on both Communist Bulgaria and Greek myth, so—yep, still picking this one up. —JHM

May 14

This Strange Eventful History by Claire Messud [F]

I read an ARC of this enthralling fictionalization of Messud’s family history—people wandering the world during much of the 20th century, moving from Algeria to France to North America— and it is quite the story, with a postscript that will smack you on the side of the head and make you re-think everything you just read. I can't recommend this enough. —CK

Woodworm by Layla Martinez, tr. Sophie Hughes and Annie McDermott [F]

Martinez’s debut novel takes cabin fever to the max in this story of a grandmother, granddaughter, and their haunted house, set against the backdrop of the Spanish Civil War. As the story unfolds, so do the house’s secrets, the two women must learn to collaborate with the malevolent spirits living among them. Mariana Enriquez says that this "tense, chilling novel tells a story of specters, class war, violence, and loneliness, as naturally as if the witches had dictated this lucid, terrible nightmare to Martínez themselves.” —LA

Self Esteem and the End of the World by Luke Healy [NF]

Ah, writers writing about writing. A tale as old as time, and often timeworn to boot. But graphic novelists graphically noveling about graphic novels? (Verbing weirds language.) It still feels fresh to me! Enter Healy's tale of "two decades of tragicomic self-discovery" following a protagonist "two years post publication of his latest book" and "grappling with his identity as the world crumbles." —JHM

All Fours by Miranda July [F]

In excruciating, hilarious detail, All Fours voices the ethically dubious thoughts and deeds of an unnamed 45-year-old artist who’s worried about aging and her capacity for desire. After setting off on a two-week round-trip drive from Los Angeles to New York City, the narrator impulsively checks into a motel 30 miles from her home and only pretends to be traveling. Her flagrant lies, unapologetic indolence, and semi-consummated seduction of a rent-a-car employee set the stage for a liberatory inquisition of heteronorms and queerness. July taps into the perimenopause zeitgeist that animates Jen Beagin’s Big Swiss and Melissa Broder’s Death Valley. —NodB

Love Junkie by Robert Plunket [F]

When a picture-perfect suburban housewife's life is turned upside down, a chance brush with New York City's gay scene launches her into gainful, albeit unconventional, employment. Set at the dawn of the AIDs epidemic, Mimi Smithers, described as a "modern-day Madame Bovary," goes from planning parties in Westchester to selling used underwear with a Manhattan porn star. As beloved as it is controversial, Plunket's 1992 cult novel will get a much-deserved second life thanks to this reissue by New Directions. (Maybe this will finally galvanize Madonna, who once optioned the film rights, to finally make that movie.) —DF

Tomorrowing by Terry Bisson [F]

The newest volume in Duke University’s Practices series collects for the first time the late Terry Bisson’s Locus column "This Month in History," which ran for two decades. In it, the iconic "They’re Made Out of Meat" author weaves an alt-history of a world almost parallel to ours, featuring AI presidents, moon mountain hikes, a 196-year-old Walt Disney’s resurrection, and a space pooch on Mars. This one promises to be a pure spectacle of speculative fiction. —DF

Chop Fry Watch Learn by Michelle T. King [NF]

A large portion of the American populace still confuses Chinese American food with Chinese food. What a delight, then, to discover this culinary history of the worldwide dissemination of that great cuisine—which moonlights as a biography of Chinese cookbook and TV cooking program pioneer Fu Pei-mei. —JHM

On the Couch ed. Andrew Blauner [NF]

André Aciman, Susie Boyt, Siri Hustvedt, Rivka Galchen, and Colm Tóibín are among the 25 literary luminaries to contribute essays on Freud and his complicated legacy to this lively volume, edited by writer, editor, and literary agent Blauner. Taking tacts both personal and psychoanalytical, these essays paint a fresh, full picture of Freud's life, work, and indelible cultural impact. —SMS

Another Word for Love by Carvell Wallace [NF]

Wallace is one of the best journalists (and tweeters) working today, so I'm really looking forward to his debut memoir, which chronicles growing up Black and queer in America, and navigating the world through adulthood. One of the best writers working today, Kiese Laymon, calls Another Word for Love as “One of the most soulfully crafted memoirs I’ve ever read. I couldn’t figure out how Carvell Wallace blurred time, region, care, and sexuality into something so different from anything I’ve read before." —SMS

The Devil's Best Trick by Randall Sullivan [NF]

A cultural history interspersed with memoir and reportage, Sullivan's latest explores our ever-changing understandings of evil and the devil, from Egyptian gods and the Book of Job to the Salem witch trials and Black Mass ceremonies. Mining the work of everyone from Zoraster, Plato, and John Milton to Edgar Allen Poe, Aleister Crowley, and Charles Baudelaire, this sweeping book chronicles evil and the devil in their many forms. --SMS

The Book Against Death by Elias Canetti, tr. Peter Filkins [NF]

In this newly-translated collection, Nobel laureate Canetti, who once called himself death's "mortal enemy," muses on all that death inevitably touches—from the smallest ant to the Greek gods—and condemns death as a byproduct of war and despots' willingness to use death as a pathway to power. By means of this book's very publication, Canetti somewhat succeeds in staving off death himself, ensuring that his words live on forever. —DF

Rise of a Killah by Ghostface Killah [NF]

"Why is the sky blue? Why is water wet? Why did Judas rat to the Romans while Jesus slept?" Ghostface Killah has always asked the big questions. Here's another one: Who needs to read a blurb on a literary site to convince them to read Ghost's memoir? —JHM

May 21

Exhibit by R.O. Kwon [F]

It's been six years since Kwon's debut, The Incendiaries, hit shelves, and based on that book's flinty prose alone, her latest would be worth a read. But it's also a tale of awakening—of its protagonist's latent queerness, and of the "unquiet spirit of an ancestor," that the author herself calls so "shot through with physical longing, queer lust, and kink" that she hopes her parents will never read it. Tantalizing enough for you? —JHM

Cecilia by K-Ming Chang [F]

Chang, the author of Bestiary, Gods of Want, and Organ Meats, returns with this provocative and oft-surreal novella. While the story is about two childhood friends who became estranged after a bizarre sexual encounter but re-connect a decade later, it’s also an exploration of how the human body and its excretions can be both pleasurable and disgusting. —CK

The Great State of West Florida by Kent Wascom [F]

The Great State of West Florida is Wascom's latest gothicomic novel set on Florida's apocalyptic coast. A gritty, ominous book filled with doomed Floridians, the passages fly by with sentences that delight in propulsive excess. In the vein of Thomas McGuane's early novels or Brian De Palma's heyday, this stylized, savory, and witty novel wields pulp with care until it blooms into a new strain of American gothic. —Zachary Issenberg

Cartoons by Kit Schluter [F]

Bursting with Kafkaesque absurdism and a hearty dab of abstraction, Schluter’s Cartoons is an animated vignette of life's minutae. From the ravings of an existential microwave to a pencil that is afraid of paper, Schluter’s episodic outré oozes with animism and uncanniness. A grand addition to City Light’s repertoire, it will serve as a zany reminder of the lengths to which great fiction can stretch. —DF

May 28

Lost Writings by Mina Loy, ed. Karla Kelsey [F]

In the early 20th century, avant-garde author, visual artist, and gallerist Mina Loy (1882–1966) led an astonishing creative life amid European and American modernist circles; she satirized Futurists, participated in Surrealist performance art, and created paintings and assemblages in addition to writing about her experiences in male-dominated fields of artistic practice. Diligent feminist scholars and art historians have long insisted on her cultural significance, yet the first Loy retrospective wasn’t until 2023. Now Karla Kelsey, a poet and essayist, unveils two never-before-published, autobiographical midcentury manuscripts by Loy, The Child and the Parent and Islands in the Air, written from the 1930s to the 1950s. It's never a bad time to be re-rediscovered. —NodB

I'm a Fool to Want You by Camila Sosa Villada, tr. Kit Maude [F]

Villada, whose debut novel Bad Girls, also translated by Maude, captured the travesti experience in Argentina, returns with a short story collection that runs the genre gamut from gritty realism and social satire to science fiction and fantasy. The throughline is Villada's boundless imagination, whether she's conjuring the chaos of the Mexican Inquisition or a trans sex worker befriending a down-and-out Billie Holiday. Angie Cruz calls this "one of my favorite short-story collections of all time." —SMS

The Editor by Sara B. Franklin [NF]

Franklin's tenderly written and meticulously researched biography of Judith Jones—the legendary Knopf editor who worked with such authors as John Updike, Sylvia Plath, Elizabeth Bowen, Anne Tyler, and, perhaps most consequentially, Julia Child—was largely inspired by Franklin's own friendship with Jones in the final years of her life, and draws on a rich trove of interviews and archives. The Editor retrieves Jones from the margins of publishing history and affirms her essential role in shaping the postwar cultural landscape, from fiction to cooking and beyond. —SMS

The Book-Makers by Adam Smyth [NF]

A history of the book told through 18 microbiographies of particularly noteworthy historical personages who made them? If that's not enough to convince you, consider this: the small press is represented here by Nancy Cunard, the punchy and enormously influential founder of Hours Press who romanced both Aldous Huxley and Ezra Pound, knew Hemingway and Joyce and Langston Hughes and William Carlos Williams, and has her own MI5 file. Also, the subject of the binding chapter is named "William Wildgoose." —JHM

June

June 4

The Future Was Color by Patrick Nathan [F]

A gay Hungarian immigrant writing crappy monster movies in the McCarthy-era Hollywood studio system gets swept up by a famous actress and brought to her estate in Malibu to write what he really cares about—and realizes he can never escape his traumatic past. Sunset Boulevard is shaking. —JHM

A Cage Went in Search of a Bird [F]

This collection brings together a who's who of literary writers—10 of them, to be precise— to write Kafka fanfiction, from Joshua Cohen to Yiyun Li. Then it throws in weirdo screenwriting dynamo Charlie Kaufman, for good measure. A boon for Kafkaheads everywhere. —JHM

We Refuse by Kellie Carter Jackson [NF]

Jackson, a historian and professor at Wellesley College, explores the past and present of Black resistance to white supremacy, from work stoppages to armed revolt. Paying special attention to acts of resistance by Black women, Jackson attempts to correct the historical record while plotting a path forward. Jelani Cobb describes this "insurgent history" as "unsparing, erudite, and incisive." —SMS

Holding It Together by Jessica Calarco [NF]

Sociologist Calarco's latest considers how, in lieu of social safety nets, the U.S. has long relied on women's labor, particularly as caregivers, to hold society together. Calarco argues that while other affluent nations cover the costs of care work and direct significant resources toward welfare programs, American women continue to bear the brunt of the unpaid domestic labor that keeps the nation afloat. Anne Helen Petersen calls this "a punch in the gut and a call to action." —SMS

Miss May Does Not Exist by Carrie Courogen [NF]

A biography of Elaine May—what more is there to say? I cannot wait to read this chronicle of May's life, work, and genius by one of my favorite writers and tweeters. Claire Dederer calls this "the biography Elaine May deserves"—which is to say, as brilliant as she was. —SMS

Fire Exit by Morgan Talty [F]

Talty, whose gritty story collection Night of the Living Rez was garlanded with awards, weighs the concept of blood quantum—a measure that federally recognized tribes often use to determine Indigenous membership—in his debut novel. Although Talty is a citizen of the Penobscot Indian Nation, his narrator is on the outside looking in, a working-class white man named Charles who grew up on Maine’s Penobscot Reservation with a Native stepfather and friends. Now Charles, across the river from the reservation and separated from his biological daughter, who lives there, ponders his exclusion in a novel that stokes controversy around the terms of belonging. —NodB

June 11

The Material by Camille Bordas [F]

My high school English teacher, a somewhat dowdy but slyly comical religious brother, had a saying about teaching high school students: "They don't remember the material, but they remember the shtick." Leave it to a well-named novel about stand-up comedy (by the French author of How to Behave in a Crowd) to make you remember both. --SMS

Ask Me Again by Clare Sestanovich [F]

Sestanovich follows up her debut story collection, Objects of Desire, with a novel exploring a complicated friendship over the years. While Eva and Jamie are seemingly opposites—she's a reserved South Brooklynite, while he's a brash Upper Manhattanite—they bond over their innate curiosity. Their paths ultimately diverge when Eva settles into a conventional career as Jamie channels his rebelliousness into politics. Ask Me Again speaks to anyone who has ever wondered whether going against the grain is in itself a matter of privilege. Jenny Offill calls this "a beautifully observed and deeply philosophical novel, which surprises and delights at every turn." —LA

Disordered Attention by Claire Bishop [NF]

Across four essays, art historian and critic Bishop diagnoses how digital technology and the attention economy have changed the way we look at art and performance today, identifying trends across the last three decades. A perfect read for fans of Anna Kornbluh's Immediacy, or the Style of Too Late Capitalism (also from Verso).

War by Louis-Ferdinand Céline, tr. Charlotte Mandell [F]

For years, literary scholars mourned the lost manuscripts of Céline, the acclaimed and reviled French author whose work was stolen from his Paris apartment after he fled to Germany in 1944, fearing punishment for his collaboration with the Nazis. But, with the recent discovery of those fabled manuscripts, War is now seeing the light of day thanks to New Directions (for anglophone readers, at least—the French have enjoyed this one since 2022 courtesy of Gallimard). Adam Gopnik writes of War, "A more intense realization of the horrors of the Great War has never been written." —DF

The Uptown Local by Cory Leadbeater [NF]

In his debut memoir, Leadbeater revisits the decade he spent working as Joan Didion's personal assistant. While he enjoyed the benefits of working with Didion—her friendship and mentorship, the more glamorous appointments on her social calendar—he was also struggling with depression, addiction, and profound loss. Leadbeater chronicles it all in what Chloé Cooper Jones calls "a beautiful catalog of twin yearnings: to be seen and to disappear; to belong everywhere and nowhere; to go forth and to return home, and—above all else—to love and to be loved." —SMS

Out of the Sierra by Victoria Blanco [NF]

Blanco weaves storytelling with old-fashioned investigative journalism to spotlight the endurance of Mexico's Rarámuri people, one of the largest Indigenous tribes in North America, in the face of environmental disasters, poverty, and the attempts to erase their language and culture. This is an important book for our times, dealing with pressing issues such as colonialism, migration, climate change, and the broken justice system. —CK

Any Person Is the Only Self by Elisa Gabbert [NF]

Gabbert is one of my favorite living writers, whether she's deconstructing a poem or tweeting about Seinfeld. Her essays are what I love most, and her newest collection—following 2020's The Unreality of Memory—sees Gabbert in rare form: witty and insightful, clear-eyed and candid. I adored these essays, and I hope (the inevitable success of) this book might augur something an essay-collection renaissance. (Seriously! Publishers! Where are the essay collections!) —SMS

Tehrangeles by Porochista Khakpour [F]

Khakpour's wit has always been keen, and it's hard to imagine a writer better positioned to take the concept of Shahs of Sunset and make it literary. "Like Little Women on an ayahuasca trip," says Kevin Kwan, "Tehrangeles is delightfully twisted and heartfelt." —JHM

Traveling: On the Path of Joni Mitchell by Ann Powers [NF]

The moment I saw this book's title—which comes from the opening (and, as it happens, my favorite) track on Mitchell's 1971 masterpiece Blue—I knew it would be one of my favorite reads of the year. Powers, one of the very best music critics we've got, masterfully guides readers through Mitchell's life and work at a fascinating slant, her approach both sweeping and intimate as she occupies the dual roles of biographer and fan. —SMS

All Desire Is a Desire for Being by René Girard, ed. Cynthia L. Haven [NF]

I'll be honest—the title alone stirs something primal in me. In honor of Girard's centennial, Penguin Classics is releasing a smartly curated collection of his most poignant—and timely—essays, touching on everything from violence to religion to the nature of desire. Comprising essays selected by the scholar and literary critic Cynthia L. Haven, who is also the author of the first-ever biographical study of Girard, Evolution of Desire, this book is "essential reading for Girard devotees and a perfect entrée for newcomers," per Maria Stepanova. —DF

June 18

Craft by Ananda Lima [F]

Can you imagine a situation in which interconnected stories about a writer who sleeps with the devil at a Halloween party and can't shake him over the following decades wouldn't compel? Also, in one of the stories, New York City’s Penn Station is an analogue for hell, which is both funny and accurate. —JHM

Parade by Rachel Cusk [F]

Rachel Cusk has a new novel, her first in three years—the anticipation is self-explanatory. —SMS

Little Rot by Akwaeke Emezi [F]

Multimedia polymath and gender-norm disrupter Emezi, who just dropped an Afropop EP under the name Akwaeke, examines taboo and trauma in their creative work. This literary thriller opens with an upscale sex party and escalating violence, and although pre-pub descriptions leave much to the imagination (promising “the elite underbelly of a Nigerian city” and “a tangled web of sex and lies and corruption”), Emezi can be counted upon for an ambience of dread and a feverish momentum. —NodB

When the Clock Broke by John Ganz [NF]

I was having a conversation with multiple brilliant, thoughtful friends the other day, and none of them remembered the year during which the Battle of Waterloo took place. Which is to say that, as a rule, we should all learn our history better. So it behooves us now to listen to John Ganz when he tells us that all the wackadoodle fascist right-wing nonsense we can't seem to shake from our political system has been kicking around since at least the early 1990s. —JHM

Night Flyer by Tiya Miles [NF]

Miles is one of our greatest living historians and a beautiful writer to boot, as evidenced by her National Book Award–winning book All That She Carried. Her latest is a reckoning with the life and legend of Harriet Tubman, which Miles herself describes as an "impressionistic biography." As in all her work, Miles fleshes out the complexity, humanity, and social and emotional world of her subject. Tubman biographer Catherine Clinton says Miles "continues to captivate readers with her luminous prose, her riveting attention to detail, and her continuing genius to bring the past to life." —SMS

God Bless You, Otis Spunkmeyer by Joseph Earl Thomas [F]

Thomas's debut novel comes just two years after a powerful memoir of growing up Black, gay, nerdy, and in poverty in 1990s Philadelphia. Here, he returns to themes and settings that in that book, Sink, proved devastating, and throws post-service military trauma into the mix. —JHM

June 25

The Garden Against Time by Olivia Laing [NF]

I've been a fan of Laing's since The Lonely City, a formative read for a much-younger me (and I'd suspect for many Millions readers), so I'm looking forward to her latest, an inquiry into paradise refracted through the experience of restoring an 18th-century garden at her home the English countryside. As always, her life becomes a springboard for exploring big, thorny ideas (no pun intended)—in this case, the possibilities of gardens and what it means to make paradise on earth. —SMS

Cue the Sun! by Emily Nussbaum [NF]

Emily Nussbaum is pretty much the reason I started writing. Her 2019 collection of television criticism, I Like to Watch, was something of a Bible for college-aged me (and, in fact, was the first book I ever reviewed), and I've been anxiously awaiting her next book ever since. It's finally arrived, in the form of an utterly devourable cultural history of reality TV. Samantha Irby says, "Only Emily Nussbaum could get me to read, and love, a book about reality TV rather than just watching it," and David Grann remarks, "It’s rare for a book to feel alive, but this one does." —SMS

Woman of Interest by Tracy O'Neill [NF]

O’Neill's first work of nonfiction—an intimate memoir written with the narrative propulsion of a detective novel—finds her on the hunt for her biological mother, who she worries might be dying somewhere in South Korea. As she uncovers the truth about her enigmatic mother with the help of a private investigator, her journey increasingly becomes one of self-discovery. Chloé Cooper Jones writes that Woman of Interest “solidifies her status as one of our greatest living prose stylists.” —LA

Dancing on My Own by Simon Wu [NF]

New Yorkers reading this list may have witnessed Wu's artful curation at the Brooklyn Museum, or the Whitney, or the Museum of Modern Art. It makes one wonder how much he curated the order of these excellent, wide-ranging essays, which meld art criticism, personal narrative, and travel writing—and count Cathy Park Hong and Claudia Rankine as fans. —JHM

[millions_email]

October Preview: The Millions Most Anticipated (This Month)

We wouldn’t dream of abandoning our vast semi–annual Most Anticipated Book Previews, but we thought a monthly reminder would be helpful (and give us a chance to note titles we missed the first time around). Here’s what we’re looking out for this month. Find more October titles at our Great Second-Half Preview, and let us know what you’re looking forward to in the comments!

OCTOBER

Killing Commendatore by Haruki Murakami (translated by Philip Gabriel and Ted Goossen): Like many before me, I once fell into Murakami’s fictional world only to emerge six months later wondering what on earth happened. So any anticipation for his new books is tempered by caution. His new novel is about a freshly divorced painter who moves to the mountains, where he finds an eerie and powerful painting called “Killing Commendatore.” Mysteries proliferate, and you will keep reading—not because you are expecting resolution but because it’s Murakami, and you’re under his spell. (Hannah)

All You Can Ever Know by Nicole Chung: This book—the first by the former editor of the much-missed site The Toast—is garnering high praise from lots of great people, among them Alexander Chee, who wrote, “I've been waiting for this writer, and this book—and everything else she'll write.” Born prematurely to Korean parents who had immigrated to America, the author was adopted by a white couple who raised her in rural Oregon, where she encountered bigotry her family couldn’t see. Chung grew curious about her past, which led her to seek out the truth of her origins and identity. (Thom)

Heavy by Kiese Laymon: Finally! This memoir has been mentioned as “forthcoming” at the end of every Kiese Laymon interview or magazine article for a few years, and I’ve been excited about it the entire time. Laymon has written one novel and one essay collection about America and race. This memoir focuses on Laymon’s own body—in the personal sense of how he treats it and lives in it, and in the larger sense of the heavy burden of a black body in America. (Janet)

Good and Mad: The Revolutionary Power of Women's Anger by Rebecca Traister: What it says in the title, by one of the foremost contemporary chroniclers of the role(s) of women in American society. It feels as though the timing of this release could not be better (that is to say, worse). Read an interview with Traister here. (Lydia)

Unsheltered by Barbara Kingsolver: The beloved novelist’s latest tells the story of Willa Knox, whose middle-class life has crumbled: The magazine she built her career around has folded, and the college where her husband had tenure has shut down. All she has is a very old house in need of serious repair. Out of desperation, she begins looking into her house’s history, hoping that she might be able to get some funding from the historical society. Through her research, she finds a kindred spirit in Thatcher Greenwood, who occupied the premises in 1871 and was an advocate of the work of Charles Darwin. Though they are separated by more than a century, Knox and Greenwood both know what it’s like to live through cultural upheaval. (Hannah)

Friday Black by Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah: In his debut short story collection, that garnered him the National Book Foundation's "5 under 35" honor, Adjei-Brenyah writes about the injustice black people face every day in America. Tackling issues like criminal justice, consumerism, and racism, these timely stories are searching for humanity in a brutal world. The collection is both heartbreaking and hopeful, and George Saunders called it “an excitement and a wonder: strange, crazed, urgent and funny.” (Carolyn)

Things to Make and Break by May-Lan Tan: This debut collection of short fiction is the most recent collaboration between Coffee House Press and Emily Books. The 11 short stories argue that relationships between two people often contain a third presence, whether that means another person or a past or future self. Tan’s sensibility has been compared to that of Joy Williams, David Lynch, and Carmen Maria Machado. (Hannah)

Gone So Long by Andre Dubus III: Whether in his fiction (House of Sand and Fog) or his nonfiction (Townie), Dubus tells blistering stories about broken lives. In his new novel, Daniel Ahern “hasn’t seen his daughter in forty years, and there is so much to tell her, but why would she listen?” Susan, his daughter, has good reason to hate Daniel—his horrific act of violence ruined their family and poisoned her life. Dubus has the preternatural power to make every storyline feel mythic, and Gone So Long rides an inevitable charge of guilt, fear, and stubborn hope. “Even after we’re gone, what we’ve left behind lives on in some way,” Dubus writes—including who we’ve left behind. (Nick R.)

Little by Edward Carey: Set in a Revolutionary Paris, a tiny, strange-looking girl named Marie is born—and then orphaned. Carey blurs the lines between fact and fiction, and art and reality, in his fictionalized tale of the little girl who grew up to become Madame Tussaud. In a starred review, Publishers Weekly writes the novel's "sumptuous turns of phrase, fashions a fantastical world that churns with vitality." (Carolyn)

White Dancing Elephants by Chaya Bhuvaneswar: Drawing comparisons to Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Margaret Atwood, and Sandra Cisneros, Bhuvaneswar’s debut collection pulls together stories of diverse women of color as they face violence, whether it be sexual, racial, or self-inflicted. The Buddha also makes an appearance, as do Hindu myths, incurable diseases, and an android. No wonder Jeff VanderMeer calls White Dancing Elephants “often provocative” as well as bold, honest, and fresh. (Kaulie)

Impossible Owls by Brian Phillips: You know meritocratic capitalism is a lie because everyone who wrote during Holly Anderson’s tenure as editor of MTV News is not presently wealthy beyond imagination, but that’s beside the point. Better yet, let’s pour one out for Grantland. Better still, let’s focus on one truth. Brian Phillips’s essays are out of this world: big-hearted, exhaustive, unrelentingly curious, and goddamned fun. It’s about time he graced us with this collection. (Nick M.)

Scribe by Alyson Hagy: In a world devastated by a civil war and fevers, an unnamed protagonist uses her gift of writing to protect herself and her family's old Appalachian farmhouse. When Hendricks, a mysterious man with a dark past, asks for a letter, the pair set off an unforeseen chain of events. Steeped in folklore and the supernatural, Kirkus's starred review called it "a deft novel about the consequences and resilience of storytelling." (Carolyn)

The Witch Elm by Tana French: For six novels now, French has taken readers inside the squabbling, backstabbing world of the (fictional) Dublin Murder Squad, with each successive book following a different detective working frantically to close a case. Now, in a twist, French has—temporarily, we hope—set aside the Murder Squad for a stand-alone book that follows the victim of a crime, a tall, handsome, faintly clueless public relations man named Toby who is nearly beaten to death when he surprises two burglars in his home. Early reviews online attest that French’s trademark immersive prose and incisive understanding of human psychology remain intact, but readers do seem to miss the Murder Squad. (Michael)

Hungry Ghost Theater by Sarah Stone: Siblings Robert and Julia Zamarin want to reveal the dangers of the world with their small political theater company while their neuroscientist sister Eva attempts to find the biological roots of empathy. While contending with fraught family dynamics, the novel touches on themes like art, free will, addiction, desire, and loss. Joan Silber writes she "found this an unforgettable book, astute, vivid, and stubbornly ambitious in its scope." (Carolyn)

Love is Blind by William Boyd: In Boyd's 15th novel, Brodie Moncur—a piano tuner with perfect pitch—flees his oppressive family in Scotland and travels across Europe. In the shadow of a (seemingly) doomed affair, the novel ruminates on the devastating power of passion, secrets, and deception. (Carolyn)

Famous Adopted People by Alice Stephens: Stephens' debut novel follows Lisa, a 27-year-old adoptee, as she travels to South Korea to find her birth mother. Equally tense, tragic, and comedic, Publishers Weekly describes the novel as a "fun-house depiction of the absurdities and horrors of the surveillance state." (Carolyn)

Girls Write Now by Girls Write Now: Containing more than one hundred essays from young women in the Girls Write Now program, a writing and mentorship program in New York City. The anthology contains stories rife with angst, uncertainty, grief, hope, honesty, and joy, and advice on writing and life from powerhouses like Roxane Gay, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, and Zadie Smith. Kirkus calls the anthology "an inspiring example of honest writing." (Carolyn)

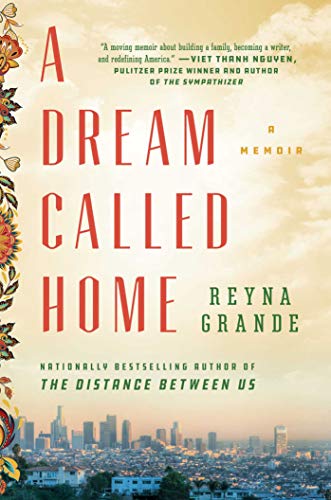

A Dream Called Home by Reyna Grande: A former undocumented Mexican immigrant, Grande's memoir explores to her journey from poverty to successful author—and the first of her family to graduate from college. Candid and heartfelt in exploring the difficulties of immigration and assimilation, Publishers Weekly's starred review called the book an "uplifting story of fortitude and resilience." (Carolyn)

Well-Read Black Girl ed. Glory Edim: Glory Edim founded Well-Read Black Girl, a Brooklyn-based book club and an online space that highlights black literature and sisterhood, and last year she produced the inaugural Well-Read Black Girl Festival. Most recently, Edim curated the Well-Read Black Girl anthology, and contributors include Morgan Jerkins, Tayari Jones, Lynn Nottage, Gabourey Sidibe, Rebecca Walker, Jesmyn Ward, Jacqueline Woodson, and Barbara Smith. The collection of essays celebrates the power of representation, visibility, and storytelling. (Zoë)

What If This Were Enough? by Heather Havrilesky: Havrilesky's, the acclaimed memoirist and columnist for The Cut's "Ask Polly" advice column, newest collection addresses our culture's obsession with self-improvement. Publishers Weekly's starred review writes "it’s a message she relates with insight, wit, and terrific prose." Tackling subjects like materialism, romance, and social media, she asks readers—who are constantly inundated with messages about productivity and betterment—to ask less of themselves, to realize that they (and their lives) are enough. (Carolyn)

[millions_ad]

Most Anticipated: The Great Second-Half 2018 Book Preview

Putting together our semi-annual Previews is a blessing and a curse. A blessing to be able to look six months into the future and see the avalanche of vital creative work coming our way; a curse because no one list can hope to be comprehensive, and no one person can hope to read all these damn books. We tried valiantly to keep it under 100, and this year, we just...couldn't. But it's a privilege to fail with such a good list: We've got new novels by Kate Atkinson, Dale Peck, Pat Barker, Haruki Murakami, Bernice McFadden, and Barbara Kingsolver. We've got a stunning array of debut novels, including one by our very own editor, Lydia Kiesling—not to mention R.O. Kwon, Ingrid Rojas Contreras, Crystal Hana Kim, Lucy Tan, Vanessa Hua, Wayétu Moore, and Olivia Laing. We've got long-awaited memoirs by Kiese Laymon and Nicole Chung. Works of nonfiction by Michiko Kakutani and Jonathan Franzen. The year has been bad, but the books will be good. (And if you don't see a title here, look out for our monthly Previews.)

As always, you can help ensure that these previews, and all our great books coverage, continue for years to come by lending your support to the site as a member. (As a thank you for their generosity, our members now get a monthly email newsletter brimming with book recommendations from our illustrious staffers.) The Millions has been running for nearly 15 years on a wing and a prayer, and we’re incredibly grateful for the love of our recurring readers and current members who help us sustain the work that we do.

JULY

The Incendiaries by R.O. Kwon: In her debut novel, Kwon investigates faith and identity as well as love and loss. Celeste Ng writes, “The Incendiaries probes the seductive and dangerous places to which we drift when loss unmoors us. In dazzlingly acrobatic prose, R.O. Kwon explores the lines between faith and fanaticism, passion and violence, the rational and the unknowable.” The Incendiaries is an American Booksellers Association Indies Introduce pick, and The New York Times recently profiled Kwon as a summer writer to watch. (Zoë)

My Year of Rest and Relaxation by Ottessa Moshfegh: Booker finalist Ottessa Moshfegh’s latest book is (as fans of hers can probably guess) both funny and deeply tender, a testament to the author’s keen eye for the sad and the weird. In it, a young woman starts a regiment of “narcotic hibernation,” prescribed to her by a psychiatrist as demented as psychiatrists come. Eventually, her drug use leads to a spate of bad side effects, which kick off a spiral of increasingly dysfunctional behavior. (Thom)

Fruit of the Drunken Tree by Ingrid Rojas Contreras: Against the backdrop of political disarray and vicious violence driven by Pablo Escobar’s drug empire, sisters Chula and Cassandra live safely in a gated Bogotá community. But when a woman from the city’s working-class slums named Petrona becomes their live-in maid, the city’s chaos penetrates the family’s comfort. Soon, Chula and Petrona’s lives are hopelessly entangled amidst devastating violence. Bay Area author Ingrid Rojas Contreras brings us this excellent and timely debut novel about the particular pressures that war exerts on the women caught up in its wake. (Ismail)

A Carnival of Losses by Donald Hall: Hall, a former United States poet laureate, earnestly began writing prose while teaching at the University of Michigan during the 1950s. Failed stories and novels during his teenage years had soured him on the genre, but then he longed to write “reminiscent, descriptive” nonfiction “by trying and failing and trying again.” Hall’s been prolific ever since, and Carnival of Losses will publish a month after his passing. Gems here include an elegy written nearly 22 years after the death of his wife, the poet Jane Kenyon. “In the months and years after her death, Jane’s voice and mine rose as one, spiraling together the images and diphthongs of the dead who were once the living, our necropoetics of grief and love in the singular absence of flesh.” For a skilled essayist, the past is always present. This book is a fitting final gift. (Nick R.)

What We Were Promised by Lucy Tan: Set in China’s metropolis Shanghai, the story is about a new rich Chinese family returning to their native land after fulfilling the American Dream. Their previous city and country have transformed as much as themselves, as have their counterparts in China. For those who want to take a look at the many contrasts and complexities in contemporary China, Tan’s work provides a valuable perspective. (Jianan)

An Ocean of Minutes by Thea Lim: In Lim’s debut novel, the world has been devastated by a flu pandemic and time travel is possible. Frank and Polly, a young couple, are learning to live in their new world—until Frank gets sick. In order to save his life, Polly travels to the future for TimeRaiser—a company set on rebuilding the world—with a plan to meet Frank there. When something in their plan goes wrong, the two try to find each other across decades. From a starred Publishers Weekly review: “Lim’s enthralling novel succeeds on every level: as a love story, an imaginative thriller, and a dystopian narrative.” (Carolyn)

How to Love a Jamaican by Alexia Arthurs: Last year, Alexia Arthurs won the Plimpton Prize for her story “Bad Behavior,” which appeared in The Paris Review’s summer issue in 2016. How to Love a Jamaican, her first book, includes that story along with several others, two of which were published originally in Vice and Granta. Readers looking for a recommendation can take one from Zadie Smith, who praised the collection as “sharp and kind, bitter and sweet.” (Thom)

Give Me Your Hand by Megan Abbott: Megan Abbott is blowing up. EW just asked if she was Hollywood’s next big novelist, due to the number of adaptations of her work currently in production, but she’s been steadily writing award-winning books for a decade. Her genre might be described as the female friendship thriller, and her latest is about two high school friends who later become rivals in the scientific academic community. Rivalries never end well in Abbott’s world. (Janet)

The Seas by Samantha Hunt: Sailors, seas, love, hauntings—in The Seas, soon to be reissued by Tin House, Samantha Hunt's fiction sees the world through a scrim of wonder and curiosity, whether it's investigating mothering (as in “A Love Story”), reimagining the late days of doddering Nikolai Tesla at the New Yorker Hotel (“The Invention of Everything Else”), or in an ill-fated love story between a young girl and a 30-something Iraq War Veteran. Dave Eggers has called The Seas "One of the most distinctive and unforgettable voices I've read in years. The book will linger…in your head for a good long time.” (Anne)

The Occasional Virgin by Hanan al-Shaykh: Novelist and playwright Hanan al-Shaykh's latest novel concerns two 30-something friends, Huda and Yvonne, who grew up together in Lebanon (the former Muslim, the latter Christian) and who now, according to the jacket copy, "find themselves torn between the traditional worlds they were born into and the successful professional identities they’ve created." Alberto Manguel calls it "A modern Jane Austen comedy, wise, witty and unexpectedly profound." I'm seduced by the title alone. (Edan)

The Marvellous Equations of the Dread by Marcia Douglas: In this massively creative work of musical magical realism, Bob Marley has been reincarnated as Fall-down and haunts a clocktower built on the site of a hanging tree in Kingston. Recognized only by a former lover, he visits with King Edward VII, Marcus Garvey, and Haile Selassie. Time isn’t quite what it usually is, either—years fly by every time Fall-down returns to his tower, and his story follows 300 years of violence and myth. But the true innovation here is in the musicality of the prose: Subtitled “A Novel in Bass Riddim,” Marvellous Equations of the Dread draws from—and continues—a long Caribbean musical tradition. (Kaulie)

The Death of Truth by Michiko Kakutani: Kakutani is best-known as the long-reigning—and frequently eviscerating—chief book critic at The New York Times, a job she left last year in order to write this book. In The Death of Truth, she considers our troubling era of alternative facts and traces the trends that have brought us to this horrific moment where the very concept of “objective reality” provokes a certain nostalgia. “Trump did not spring out of nowhere,” she told Vanity Fair in a recent interview, “and I was struck by how prescient writers like Alexis de Tocqueville and George Orwell and Hannah Arendt were about how those in power get to define what the truth is.” (Emily)

Immigrant, Montana by Amitava Kumar: Kumar, author of multiple works of fiction, nonfiction, and poetry, returns with a novel about Kailash, a young immigrant from India, coming of age and searching for love in the United States. Publishers Weekly notes (in a starred review) that “this coming-of-age-in-the-city story is bolstered by the author’s captivating prose, which keeps it consistently surprising and hilarious.” (Emily)

Brother by David Chariandy: A tightly constructed and powerful novel that tells the story of two brothers in a housing complex in a Toronto suburb during the simmering summer of 1991. Michael and Francis balance hope against the danger of having it as they struggle against prejudice and low expectations. This is set against the tense events of a fateful night. When the novel came out in Canada last year, it won the Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize and was declared one of the best of the year by many. Marlon James calls Brother "a brilliant, powerful elegy from a living brother to a lost one.” (Claire)

A Terrible Country by Keith Gessen: Familial devotion, academic glory, and the need for some space to think have combined to send Andrei back to Moscow some 20 years after his family had emigrated to America. The trip should stir up some academic fodder for his ailing career, and besides, his aging baba Seva could really use the help. For her part, baba Seva never wavers in her assessment of Andrei’s attempt to make a go of it in 200-aughtish Russia: “This is a terrible country,” she tells him. Repeatedly. Perhaps he should have listened. This faux memoir is journalist and historian Keith Gessen’s second novel and an essential addition to the “Before You Go to Russia, Read…” list. (Il’ja)

The Lost Country by William Gay: After Little Sister Death, Gay’s 2015 novel that slipped just over the border from Southern gothic into horror, longtime fans of his dark realism (where the real is ever imbued with the fantastic) will be grateful to indie publisher Dzanc Books for one more posthumous novel from the author. Protagonist Billy Edgewater returns to eastern Tennessee after two years in the Navy to see his dying father. Per Kirkus, the picaresque journey takes us through “italicized flashbacks, stream-of-consciousness interludes, infidelities, prison breaks, murderous revenge, biblical language, and a deep kinship between the land and its inhabitants,” and of course, there’s also a one-armed con man named Roosterfish, who brings humor into Gay’s bleak (drunken, violent) and yet still mystical world of mid-1950s rural Tennessee. (Sonya)

Comemadre by Roque Larraquy (translated by Heather Cleary): A fin de siècle Beunos Aires doctor probes a little too closely when examining the threshold between life and death. A 21st-century artist discovers the ultimate in transcendence and turns himself into an objet d'art. In this dark, dense, surprisingly short debut novel by the Argentinian author, we’re confronted with enough grotesqueries to fill a couple Terry Gilliam films and, more importantly, with the idea that the only real monsters are those that are formed out of our own ambition. (Il’ja)

Now My Heart Is Full by Laura June: "It was my mother I thought of as I looked down at my new daughter," writes Laura June in her debut memoir about how motherhood has forced her to face, reconcile, and even reassess her relationship with her late mother, who was an alcoholic. Roxane Gay calls it “warm and moving,” and Alana Massey writes, “Laura June triumphs by resisting the inertia of inherited suffering and surrendering to the possibility of a boundless, unbreakable love.” Fans of Laura June's parenting essays on The Cut will definitely want to check this one out. (Edan)

OK, Mr. Field by Katherine Kilalea: In this debut novel, a concert pianist (the eponymous Mr. Field) spends his payout from a train accident on a replica of Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye. And then his wife vanishes. In a starred review, Publishers Weekly called the book “a striking, singular debut” and “a disorienting and enthralling descent into one man’s peculiar malaise.” You can whet your appetite with this excerpt in The Paris Review. Kilalea, who is from South Africa and now lives in London, is also the author of the poetry collection One Eye’d Leigh. (Edan)

Nevada Days by Bernardo Atxaga (translated by Margaret Jull Costa): Though it’s difficult to write a truly new European travelogue, the Basque writer Bernardo Atxaga seems to have found a way. After spurning Harvard—who tried to recruit him to be an author in residence—Atxaga took an offer to spend nine months at the Center for Basque Studies at the University of Nevada, Reno, which led to this book about his tenure in the Silver State during the run-up to Obama's election. Though it’s largely a fictionalized account, the book contains passages and stories the author overheard. (Thom)

Interior by Thomas Clerc (translated by Jeffrey Zuckerman): Give it to Thomas Clerc: The French writer isn’t misleading his readers with the title of this book. At heart, Interior is a tour of the author’s apartment, animated with a comic level of detail and consideration. Every object and appliance gets a history, and the author gives opinions on things like bathroom reading material. Like Samuel Beckett’s fiction, Interior comes alive through its narrator, whose quirkiness helps shepherd the reader through a landscape of tedium. (Thom)

Eden by Andrea Kleine: Hope and her sister, Eden, were abducted as children, lured into a van by a man they thought was their father’s friend; 20 years later, Hope’s life as a New York playwright is crumbling when she hears their abductor is up for parole. Eden’s story could keep him locked away, but nobody knows where she is, so Hope takes off to look for her, charting a cross-country path in a run-down RV. The author of Calf, Kleine is no stranger to violence, and Eden is a hard, sometimes frightening look at the way trauma follows us. (Kaulie)

Unclean Jobs for Women and Girls by Alissa Nutting: The latest collection from one of America’s most audaciously interesting writers follows her last two novels, in which she inverted the Lolita story and satirized Silicon Valley, respectively. Somewhere in between, she also wrote about her love of hot dogs. Oh, and this collection’s title is clearly a nod to Lucia Berlin. Let’s be real for a minute: If you need more than that to buy this book, you’re not my friend, you’ve got bad taste, and you should keep scrolling. (Nick M.)

Suicide Club by Rachel Heng: What if we could live forever? Or: When is life no longer, you know, life? Heng’s debut novel, set in a futuristic New York where the healthy have a shot at immortality, probes those questions artfully but directly. Lea Kirino trades organs on the New York Stock Exchange and might never die, but when she runs into her long-disappeared father and meets the other members of his Suicide Club, she begins to wonder what life will cost her. Part critique of the American cult of wellness, part glittering future with a nightmare undercurrent, Suicide Club is nothing if not deeply imaginative and timely. (Kaulie)

The Samurai by Shusaku Endo (translated by Van C. Gessel): In early 17th-century Japan, four low-ranking samurai and a Jesuit priest set off for la Nueva España (Mexico) on a trade mission. What could go wrong? The question of whether there can ever be substantive interplay between the core traditions of the West and the Far East—or whether the dynamic is somehow doomed, organically, to the superficial—is a recurring motif in Endo’s work much as it was in his life. Endo’s Catholic faith lent a peculiar depth to his writing that’s neither parochial nor proselytizing but typically, as in this New Directions reprint, thick with adventure. (Il’ja)

If You See Me, Don’t Say Hi by Neel Patel: The characters in these 11 stories, nearly all of whom are first-generation Indian immigrants, are gay and straight, highly successful and totally lost, meekly traditional and boldly transgressive, but as they navigate a familiar contemporary landscape of suburban malls and social media stalking, they come off as deeply—and compellingly—American. (Michael)

Homeplace by John Lingan: Maybe it’s true that a dive bar shouldn’t have a website, but probably that notion gets thrown out the window when the bar's longtime owner gave Patsy Cline her first break. In the same way, throw out your notions of what a hyper-localized examination of a small-town bar can be. In Lingan’s hands, the Troubadour explodes like a shattered glass, shards shot beyond Virginia, revealing something about ourselves—all of us—if we can catch the right glints in the pieces. (Nick M.)

Early Work by Andrew Martin: In this debut, a writer named Peter Cunningham slowly becomes aware that he’s not the novelist he wants to be. He walks his dog, writes every day, and teaches at a woman’s prison, but he still feels directionless, especially in comparison to his medical student girlfriend. When he meets a woman who’s separated from her fiance, he starts to learn that inspiration is always complex. (Thom)

AUGUST

A River of Stars by Vanessa Hua: A factory worker named Scarlett Chen is having an affair with Yeung—her boss—when her life is suddenly turned upside down. After she becomes pregnant with Yeung’s son, Scarlett is sent to a secret maternity home in Los Angeles so that the child will be born with the privileges of American citizenship. Distressed at her isolation, Scarlett flees to San Francisco’s Chinatown with a teenage stowaway named Daisy. Together, they disappear into a community of immigrants that remains hidden to most Americans. While they strive for their version of the American dream, Yeung will do anything to secure his son’s future. In a time when immigration policy has returned to the center of our national politics, Bay Area author Vanessa Hua delivers a book that explores the motivations, fears, and aspirations that drive people to migrate. (Ismail)

Flights by Olga Tokarczuk (translated by Jennifer Croft): The 116 vignettes that make up this collection have been called digressive, discursive, and speculative. My adjectives: disarming and wonderfully encouraging. Whether telling the story of the trip that brought Chopin’s heart back to Warsaw or of a euthanasia pact between two sweethearts, Croft’s translation from Polish is light as a feather yet captures well the economy and depth of Tokarczuk’s deceptively simple style. A welcome reminder of how love drives out fear and also a worthy Man Booker International winner for 2018. (Il’ja)

If You Leave Me by Crystal Hana Kim: Kim, a Columbia MFA graduate and contributing editor of Apogee Journal, is drawing rave advance praise for her debut novel. If You Leave Me is a family saga and romance set during the Korean War and its aftermath. Though a historical drama, its concerns—including mental illness and refugee life—could not be more timely. (Adam)

Praise Song for the Butterflies by Bernice McFadden: On the heels of her American Book Award- and NAACP Image Award-winning novel The Book of Harlan, McFadden’s 10th novel, Praise Song for the Butterflies, gives us the story of Abeo, a privileged 9-year-old girl in West Africa who is sacrificed by her family into a brutal life of ritual servitude to atone for the father’s sins. Fifteen years later, Abeo is freed and must learn how to heal and live again. A difficult story that, according to Kirkus, McFadden takes on with “riveting prose” that “keeps the reader turning pages.” (Sonya)

The Third Hotel by Laura Van Den Berg: When Clare arrives in Havana, she is surprised to find her husband, Richard, standing in a white linen suit outside a museum (surprised, because she thought Richard was dead). The search for answers sends Clare on a surreal journey; the distinctions between reality and fantasy blur. Her role in Richard's death and reappearance comes to light in the streets of Havana, her memories of her marriage, and her childhood in Florida. Lauren Groff praises the novel as “artfully fractured, slim and singular.” (Claire)

Severance by Ling Ma: In this funny, frightening, and touching debut, office drone Candace is one of only a few New Yorkers to survive a plague that’s leveled the city. She joins a group, led by IT guru Bob, in search of the Facility, where they can start society anew. Ling Ma manages the impressive trick of delivering a bildungsroman, a survival tale, and satire of late capitalist millennial angst in one book, and Severance announces its author as a supremely talented writer to watch. (Adam)

Night Soil by Dale Peck: Author and critic Dale Peck has made a career out of telling stories about growing up queer; with Night Soil, he might have finally hit upon his most interesting and well-executed iteration of that story since his 1993 debut. The novel follows Judas Stammers, an eloquently foul-mouthed and compulsively horny heir to a Southern mining fortune, and his mother Dixie, a reclusive artist famous for making technically perfect pots. Living in the shadow of the Academy that their ancestor Marcus Stammers founded in order to educate—and exploit—his former slaves, Judas and Dixie must confront the history of their family’s complicity in slavery and environmental degradation. This is a hilarious, thought-provoking, and lush novel about art’s entanglement with America’s original sin. (Ismail)

Summer by Karl Ove Knausgaard: After the success of his six-part autofiction project My Struggle, Norwegian author Karl Knausgaard embarked on a new project: a quartet of memoiristic reflections on the seasons. Knausgaard wraps up the quartet with Summer, an intensely observed meditation on the Swedish countryside that the author has made a home in with his family. (Ismail)

Ohio by Stephen Markley: Ohio is an ambitious novel composed of the stories of four residents of New Canaan, Ohio, narratively unified by the death of their mutual friend in Iraq. Markley writes movingly about his characters, about the wastelands of the industrial Midwest, about small towns with economic and cultural vacuums filled by opioids, Donald Trump, and anti-immigrant hatred. This is the kind of book people rarely attempt to write any more, a Big American Novel that seeks to tell us where we live now. (Adam)

French Exit by Patrick deWitt: In this new novel by Patrick deWitt, bestselling author of The Sisters Brothers and Undermajordomo Minor, a widow and her son try to escape their problems (scandal, financial ruin, etc.) by fleeing to Paris. Kirkus Reviews calls it “a bright, original yarn with a surprising twist,” and Maria Semple says it's her favorite deWitt novel yet, its dialogue "dizzyingly good." According to Andrew Sean Greer the novel is "brilliant, addictive, funny and wise." (Edan)

Notes from the Fog by Ben Marcus: If you’ve read Marcus before, you know what you’re in for: a set of bizarre stories that are simultaneously terrifying and hysterical, fantastical and discomfortingly realistic. For example, in “The Grow-Light Blues,” which appeared in The New Yorker a few years back, a corporate employee tests a new nutrition supplement—the light from his computer screen. The results are not pleasant. With plots that seem like those of Black Mirror, Marcus presents dystopian futures that are all the more frightening because they seem possible. (Ismail)