Mentioned in:

The Great Fall 2024 Book Preview

With the arrival of autumn comes a deluge of great books. Here you'll find a sampling of new and forthcoming titles that caught our eye here at The Millions, and that we think might catch yours, too. Some we’ve already perused in galley form; others we’re eager to devour based on their authors, plots, or subject matters. We hope your next fall read is among them.

—Sophia Stewart, editor

October

Season of the Swamp by Yuri Herrera, tr. Lisa Dillman [F]

What it is: An epic, speculative account of the 18 months that Benito Juárez spent in New Orleans in 1853-54, years before he became the first and only Indigenous president of Mexico.

Who it's for: Fans of speculative history; readers who appreciate the magic that swirls around any novel set in New Orleans. —Claire Kirch

The Black Utopians by Aaron Robertson [NF]

What it is: An exploration of Black Americans' pursuit and visions of utopia—both ideological and physical—that spans the Reconstruction era to the present day and combines history, memoir, and reportage.

Who it's for: Fans of Saidiya Hartman's Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments and Kristen R. Ghodsee's Everyday Utopia. —Sophia M. Stewart

The Third Realm by Karl Ove Knausgaard, tr. Martin Aitken [F]

What it is: The third installment in Knausgaard's Morning Star series, centered on the appearance of a mysterious new star in the skies above Norway.

Who it's for: Real Knausgaard heads only—The Wolves of Eternity and Morning Star are required reading for this one. —SMS

Brown Women Have Everything by Sayantani Dasgupta [NF]

What it is: Essays on the contradictions and complexities of life as an Indian woman in America, probing everything from hair to family to the joys of travel.

Who it's for: Readers of Durga Chew-Bose, Erika L. Sánchez, and Tajja Isen. —SMS

The Plot Against Native America by Bill Vaughn [F]

What it is: The first narrative history of Native American boarding schools— which aimed "civilize" Indigenous children by violently severing them from their culture— and their enduring, horrifying legacy.

Who it's for: Readers of Ned Blackhawk and Kathleen DuVal. —SMS

The Mighty Red by Louise Erdrich [F]

What it is: Erdrich's latest novel set in North Dakota's Red River Valley is a tale of the intertwined lives of ordinary people striving to survive and even thrive in their rural community, despite environmental upheavals, the 2008 financial crisis, and other obstacles.

Who it's for: Readers of cli-fi; fans of Linda LeGarde Grover and William Faulkner. —CK

The Position of Spoons by Deborah Levy [NF]

What it is: The second book from Levy in as many years, diverging from a recent streak of surrealist fiction with a collection of essays marked by exceptional observance and style.

Who it's for: Close lookers and the perennially curious. —John H. Maher

The Bog Wife by Kay Chronister [F]

What it's about: The Haddesley family has lived on the same West Virginia bog for centuries, making a supernatural bargain with the land—a generational blood sacrifice—in order to do so—until an uncovered secret changes everything.

Who it's for: Readers of Karen Russell and Jeff VanderMeer; anyone who has ever used the phrase "girl moss." —SMS

The Great When by Alan Moore [F]

What it's about: When an 18-year old book reseller comes across a copy of a book that shouldn’t exist, it threatens to upend not just an already post-war-torn London, but reality as we know it.

Who it's for: Anyone looking for a Sherlock Holmes-style mystery dipped in thaumaturgical psychedelia. —Daniella Fishman

The Message by Ta-Nehisi Coates [NF]

What it's about: One of our sharpest critical thinkers on social justice returns to nonfiction, nearly a decade after Between the World and Me, visiting Dakar, to contemplate enslavement and the Middle Passage; Columbia, S.C., as a backdrop for his thoughts on Jim Crow and book bans; and the Israeli-occupied West Bank, where he sees contemporary segregation in the treatment of Palestinians.

Who it’s for: Fans of James Baldwin, George Orwell, and Angela Y. Davis; readers of Nikole Hannah-Jones’s The 1619 Project and Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste, to name just a few engagements with national and racial identity. —Nathalie op de Beeck

Abortion by Jessica Valenti [NF]

What it is: Columnist and memoirist Valenti, who tracks pro-choice advocacy and attacks on the right to choose in her Substack, channels feminist rage into a guide for freedom of choice advocacy.

Who it’s for: Readers of Robin Marty’s The New Handbook for a Post-Roe America, #ShoutYourAbortion proponents, and followers of Jennifer Baumgartner’s [I Had an Abortion] project. —NodB

Gifted by Suzuki Suzumi, tr. Allison Markin Powell [F]

What it's about: A young sex worker in Tokyo's red-light district muses on her life and recounts her abusive mother's final days, in what is Suzuki's first novel to be translated into English.

Who it's for: Readers of Susan Boyt and Mieko Kanai; fans of moody, introspective fiction; anyone with a fraught relationship to their mother. —SMS

Childish Literature by Alejandro Zambra, tr. Megan McDowell [F]

What it is: A wide-ranging collection of stories, essays, and poems that explore childhood, fatherhood, and family.

Who it's for: Fans of dad lit (see: Lucas Mann's Attachments, Keith Gessen's Raising Raffi, Karl Ove Knausgaard's seasons quartet, et al). —SMS

Books Are Made Out of Books ed. Michael Lynn Crews [NF]

What it is: A mining of the archives of the late Cormac McCarthy with a focus on the famously tight-lipped author's literary influences.

Who it's for: Anyone whose commonplace book contains the words "arquebus," "cordillera," or "vinegaroon." —JHM

Slaveroad by John Edgar Wideman [F]

What it is: A blend of memoir, fiction, and history that charts the "slaveroad" that runs through American history, spanning the Atlantic slave trade to the criminal justice system, from the celebrated author of Brothers and Keepers.

Who it's for: Fans of Clint Smith and Ta-Nehisi Coates. —SMS

Linguaphile by Julie Sedivy [NF]

What it's about: Linguist Sedivy reflects on a life spent loving language—its beauty, its mystery, and the essential role it plays in human existence.

Who it's for: Amateur (or professional) linguists; fans of the podcast A Way with Words (me). —SMS

An Image of My Name Enters America by Lucy Ives [NF]

What it is: A collection of interrelated essays that connect moments from Ives's life to larger questions of history, identity, and national fantasy,

Who it's for: Fans of Ives, one of our weirdest and most wondrous living writers—duh; anyone with a passing interest in My Little Pony, Cold War–era musicals, or The Three Body Problem, all of which are mined here for great effect. —SMS

Women's Hotel by Daniel Lavery [F]

What it is: A novel set in 1960s New York City, about the adventures of the residents of a hotel providing housing for young women that is very much evocative of the real-life legendary Barbizon Hotel.

Who it's for: Readers of Mary McCarthy's The Group and Rona Jaffe's The Best of Everything. —CK

The World in Books by Kenneth C. Davis [NF]

What it is: A guide to 52 of the most influential works of nonfiction ever published, spanning works from Plato to Ida B. Wells, bell hooks to Barbara Ehrenreich, and Sun Tzu to Joan Didion.

Who it's for: Lovers of nonfiction looking to cover their canonical bases. —SMS

Blue Light Hours by Bruna Dantas Lobato [F]

What it's about: Through the emanating blue-glow of their computer screens, a mother and daughter, four-thousand miles apart, find solace and loneliness in their nightly Skype chats in this heartstring-pulling debut.

Who it's for: Someone who needs to be reminded to CALL YOUR MOTHER! —DF

Riding Like the Wind by Iris Jamahl Dunkle [NF]

What it is: The biography of Sanora Babb, a contemporary of John Steinbeck's whose field notes and interviews with Dust Bowl migrants Steinbeck relied upon to write The Grapes of Wrath.

Who it's for: Steinbeck fans and haters alike; readers of Kristin Hannah's The Four Winds and the New York Times Overlooked column; anyone interested in learning more about the Dust Bowl migrants who fled to California hoping for a better life. —CK

Innie Shadows by Olivia M. Coetzee [F]

What it is: a work of crime fiction set on the outskirts of Cape Town, where a community marred by violence seeks justice and connection; also the first novel to be translated from Kaaps, a dialect of Afrikaans that was until recently only a spoken language.

Who it's for: fans of sprawling, socioeconomically-attuned crime dramas a la The Wire. —SMS

Dorothy Parker in Hollywood by Gail Crowther [NF]

What it is: A history of the famous wit—and famous New Yorker—in her L.A. era, post–Algonquin Round Table and mid–Red Scare.

Who it's for: Owners of a stack of hopelessly dog-eared Joan Didion paperbacks. —JHM

The Myth of American Idealism by Noam Chomsky and Nathan J. Robinson [NF]

What it is: A potent critique of the ideology behind America's foreign interventions and its status as a global power, and an treatise on how the nation's hubristic pursuit of "spreading democracy" threatens not only the delicate balance of global peace, but the already-declining health of our planet.

Who it's for: Chomskyites; policy wonks and casual critics of American recklessness alike. —DF

Mysticism by Simon Critchley [NF]

What it is: A study of mysticism—defined as an experience, rather than religious practice—by the great British philosopher Critchley, who mines music, poetry, and literature along the way.

Who it's for: Readers of John Gray, Jorge Luis Borges, and Simone Weil. —SMS

Q&A by Adrian Tomine [NF]

What it is: The Japanese American creator of the Optic Nerve comic book series for D&Q, and of many a New Yorker cover, shares his personal history and his creative process in this illustrated unburdening.

Who it’s for: Readers of Tomine’s melancholic, sometimes cringey, and occasionally brutal collections of comics short stories including Summer Blonde, Shortcomings, and Killing and Dying. —NodB

Sonny Boy by Al Pacino [NF]

What it is: Al Pacino's memoir—end of description.

Who it's for: Cinephiles; anyone curious how he's gonna spin fumbling Diane Keaton. —SMS

Seeing Baya by Alice Kaplan [NF]

What it is: The first biography of the enigmatic and largely-forgotten Algerian artist Baya Mahieddine, who first enchanted midcentury Paris as a teenager.

Who it's for: Admirers of Leonora Carrington, Hilma af Klint, Frida Kahlo, and other belatedly-celebrated women painters. —SMS

Absolution by Jeff VanderMeer [F]

What it is: A surprise return to the Area X, the stretch of unforbidding and uncanny coastline in the hit Southern Reach trilogy.

Who it's for: Anyone who's heard this song and got the reference without Googling it. —JHM

The Four Horsemen by Nick Curtola [NF]

What it is: The much-anticipated cookbook from the team behind Brooklyn's hottest restaurant (which also happens to be co-owned by James Murphy of LCD Soundsystem).

Who it's for: Oenophiles; thirty-somethings who live in north Williamsburg (derogatory). —SMS

Seeing Further by Esther Kinsky, tr. Caroline Schmidt [F]

What it's about: An unnamed German woman embarks on the colossal task of reviving a cinema in a small Hungarian village.

Who it's for: Fans of Jenny Erpenbeck; anyone charmed by Cinema Paradiso (not derogatory!). —SMS

Ripcord by Nate Lippens [NF]

What it's about: A novel of class, sex, friendship, and queer intimacy, written in delicious prose and narrated by a gay man adrift in Milwaukee.

Who it's for: Fans of Brontez Purnell, Garth Greenwell, Alexander Chee, and Wayne Koestenbaum. —SMS

The Use of Photography by Annie Ernaux and Marc Marie, tr. Alison L. Strayer [NF]

What it's about: Ernaux's love affair with Marie, a journalist, while she was undergoing treatment for cancer, and their joint project to document their romance.

Who it's for: The Ernaux hive, obviously; readers of Sontag's On Photography and Janet Malcolm's Still Pictures. —SMS

Nora Ephron at the Movies by Ilana Kaplan [NF]

What it is: Kaplan revisits Nora Ephron's cinematic watersheds—Silkwood, Heartburn, When Harry Met Sally, You've Got Mail, and Sleepless in Seattle—in this illustrated book. Have these iconic stories, and Ephron’s humor, weathered more than 40 years?

Who it’s for: Film history buffs who don’t mind a heteronormative HEA; listeners of the Hot and Bothered podcast; your coastal grandma. —NodB

[millions_email]

The Philosophy of Translation by Damion Searls [NF]

What it is: A meditation on the act and art of translation by one of today's most acclaimed practitioners, best known for his translations of Fosse, Proust, et al.

Who it's for: Regular readers of Words Without Borders and Asymptote; professional and amateur literary translators alike. —SMS

Salvage by Dionne Brand

What it is: A penetrating reevaluation of the British literary canon and the tropes once shaped Brand's reading life and sense of self—and Brand’s first major work of nonfiction since her landmark A Map to the Door of No Return.

Who it's for: Readers of Christina Sharpe's Ordinary Notes and Elizabeth Hardwick's Seduction and Betrayal. —SMS

Masquerade by Mike Fu [F]

What it's about: Housesitting for an artist friend in present-day New York, Meadow Liu stumbles on a novel whose author shares his name—the first of many strange, haunting happenings that lead up to the mysterious disappearance of Meadow's friend.

Who it's for: fans of Ed Park and Alexander Chee. —SMS

November

The Beggar Student by Osamu Dazai, tr. Sam Bett [F]

What it is: A novella in the moody vein of Dazai’s acclaimed No Longer Human, following the 30-something “fictional” Dazai into another misadventure spawned from a hubristic spat with a high schooler.

Who it's for: Longtime readers of Dazai, or new fans who discovered the midcentury Japanese novelist via TikTok and the Bungo Stray Dogs anime. —DF

In Thrall by Jane DeLynn [F]

What it is: A landmark lesbian bildungsroman about 16-year-old Lynn's love affair with her English teacher, originally published in 1982.

Who it's for: Fans of Joanna Russ's On Strike Against God and Edmund White's A Boy's Own Story —SMS

Washita Love Child by Douglas Kent Miller [NF]

What it is: The story of Jesse Ed Davis, the Indigenous musician who became on of the most sought after guitarists of the late '60s and '70s, playing alongside B.B. King, Bob Dylan, John Lennon, and more.

Who it's for: readers of music history and/or Indigenous history; fans of Joy Harjo, who wrote the foreword. —SMS

Set My Heart on Fire by Izumi Suzuki, tr. Helen O'Horan [F]

What it is: Gritty, sexy, and wholly rock ’n’ roll, Suzuki’s first novel translated into English (following her story collection, Hit Parade of Tears) follows 20-year-old Izumi navigating life, love, and music in the underground scene in '70s Japan.

Who it's for: Fans of Meiko Kawakami, Ursula K. Le Guin, and Marlowe Granados's Happy Hour. —DF

Didion & Babitz by Lili Anolik [NF]

What it is: A dual portrait of Joan Didion and Eve Babitz, who are so often compared to—and pitted against—each other on the basis of their mutual Los Angeles milieu.

Who it's for: Fans or haters of either writer (the book is fairly pro-Babitz, often at Didion's expense); anyone who has the Lit Hub Didion tote bag. —SMS

The Endless Refrain by David Rowell [NF]

What it's about: How the rise of music streaming, demonitizing of artist revenue, and industry tendency toward nostalgia have laid waste to the musical landscape, and the future of music culture.

Who it's for: Fans of Kyle Chayka, Spence Kornhaber, and Lindsay Zoladz. —SMS

Every Arc Bends Its Radian by Sergio De La Pava [F]

What it is: A mind- and genre-bending detective story set in Cali, Colombia, that blends high-stakes suspense with rigorous philosophy.

Who it's for: Readers of Raymond Chandler, Thomas Pynchon, and Jules Verne. —SMS

Something Close to Nothing by Tom Pyun [F]

What it’s about: At the airport with his white husband Jared, awaiting a flight to Cambodia to meet the surrogate mother carrying their adoptive child-to-be, Korean American Wynn decides parenthood isn't for him, and bad behavior ensues.

Who it’s for: Pyun’s debut is calculated to cut through saccharine depictions of queer parenthood—could pair well with Torrey Peters’s Detransition, Baby. —NodB

Rosenfeld by Maya Kessler [F]

What it is: Kessler's debut—rated R for Rosenfeld—follows one Noa Simmons through the tumultuous and ultimately profound power play that is courting (and having a lot of sex with) the titular older man who soon becomes her boss.

Who it's for: Fans of Sex and the City, Raven Leilani’s Luster, and Coco Mellor’s Cleopatra and Frankenstein. —DF

Lazarus Man by Richard Price [F]

What it is: The former The Wire writer offers yet another astute chronicle of urban life, this time of an ever-changing Harlem.

Who it's for: Fans of Colson Whitehead's Crook Manifesto and Paul Murray's The Bee Sting—and, of course, The Wire. —SMS

Stranger Than Fiction by Edwin Frank [NF]

What it is: An astute curveball of a read on the development and many manifestations of the novel throughout the tumultuous 20th century.

Who it's for: Readers who look at a book's colophon before its title. —JHM

Letters to His Neighbor by Marcel Proust, tr. Lydia Davis

What it is: A collection of Proust’s tormented—and frequently hilarious—letters to his noisy neighbor which, in a diligent translation from Davis, stand the test of time.

Who it's for: Proust lovers; people who live below heavy-steppers. —DF

Context Collapse by Ryan Ruby [NF]

What it is: A self-proclaimed "poem containing a history of poetry," from ancient Greece to the Iowa Workshop, from your favorite literary critic's favorite literary critic.

Who it's for: Anyone who read and admired Ruby's titanic 2022 essay on The Waste Land; lovers of poetry looking for a challenge. —SMS

How Sondheim Can Change Your Life by Richard Schoch [NF]

What it's about: Drama professor Schoch's tribute to Stephen Sondheim and the life lessons to be gleaned from his music.

Who it's for: Sondheim heads, former theater kids, end of list. —SMS

The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer [NF]

What it is: 2022 MacArthur fellow and botanist Kimmerer, an enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, (re)introduces audiences to a flowering, fruiting native plant beloved of foragers and gardeners.

Who it’s for: The restoration ecologist in your life, along with anyone who loved Braiding Sweetgrass and needs a nature-themed holiday gift. —NodB

My Heart Belongs in an Empty Big Mac Container Buried Beneath the Ocean Floor by Homeless [F]

What it is: A pseudonymous, tenderly comic novel of blue whales and Golden Arches, mental illness and recovery.

Who it's for: Anyone who finds Thomas Pynchon a bit too staid. —JHM

Yoke and Feather by Jessie van Eerden [NF]

What it's about: Van Eerden's braided essays explore the "everyday sacred" to tease out connections between ancient myth and contemporary life.

Who it's for: Readers of Courtney Zoffness's Spilt Milk and Jeanna Kadlec's Heretic. —SMS

Camp Jeff by Tova Reich [F]

What it's about: A "reeducation" center for sex pests in the Catskills, founded by one Jeffery Epstein (no, not that one), where the dual phenomena of #MeToo and therapyspeak collide.

Who it's for: Fans of Philip Roth and Nathan Englander; cancel culture skeptics. —SMS

Selected Amazon Reviews by Kevin Killian [NF]

What it is: A collection of 16 years of Killian’s funniest, wittiest, and most poetic Amazon reviews, the sheer number of which helped him earn the rarefied “Top 100” and “Hall of Fame” status on the site.

Who it's for: Fans of Wayne Koestenbaum and Dodie Bellamy, who wrote introduction and afterword, respectively; people who actually leave Amazon reviews. —DF

Cher by Cher [NF]

What it is: The first in a two-volume memoir, telling the story of Cher's early life and ascendent career as only she can tell it.

Who it's for: Anyone looking to fill the My Name Is Barbra–sized hole in their heart, or looking for something to tide them over until the Liza memoir drops. —SMS

The City and Its Uncertain Walls by Haruki Murakami, tr. Philip Gabriel [F]

What it is: Murakami’s first novel in over six years returns to the high-walled city from his 1985 story "Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World" with one man's search for his lost love—and, simultaneously, an ode to libraries and literature itself.

Who it's for: Murakami fans who have long awaited his return to fiction. —DF

American Bulk by Emily Mester [NF]

What it's about: Reflecting on what it means to "live life to the fullest," Mester explores the cultural and personal impacts of America’s culture of overconsumption, from Costco hauls to hoarding to diet culture—oh my!

Who it's for: Lovers of sustainability; haters of excess; skeptics of the title essay of Becca Rothfeld's All Things Are Too Small. —DF

The Icon and the Idealist by Stephanie Gorton [NF]

What it is: A compelling look at the rivalry between Margaret Sanger, of Planned Parenthood fame, and Mary Ware Dennett, who each held radically different visions for the future of birth control.

Who it's for: Readers of Amy Sohn's The Man Who Hated Women and Katherine Turk's The Women of NOW; anyone interested in the history of reproductive rights. —SMS

December

Rental House by Weike Wang [F]

What it's about: Married college sweethearts invite their drastically different families on a Cape Code vacation, raising questions about marriage, intimacy, and kinship.

Who it's for: Fans of Wang's trademark wit and sly humor (see: Joan Is Okay and Chemistry); anyone with an in-law problem.

Woo Woo by Ella Baxter [F]

What it's about: A neurotic conceptual artist loses her shit in the months leading up to an exhibition that she hopes will be her big breakout, poking fun at the tropes of the "art monster" and the "woman of the verge" in one fell, stylish swoop.

Who it's for: Readers of Sheena Patel's I'm a Fan and Chris Kraus's I Love Dick; any woman who is grateful to but now also sort of begrudges Jenny Offil for introducing "art monster" into the lexicon (me). —SMS

Berlin Atomized by Julia Kornberg, tr. Jack Rockwell and Julia Kornberg [F]

What it's about: Spanning 2001 to 2034, three Jewish and downwardly mobile siblings come of age in various corners of the world against the backdrop of global crisis.

Who it's for: Fans of Catherine Lacey's Biography of X and Joshua Cohen's The Netanyahus. —SMS

Sand-Catcher by Omar Khalifah, tr. Barbara Romaine [F]

What it is: A suspenseful, dark satire of memory and nation, in which four young Palestinian journalists at a Jordanian newspaper are assigned to interview an elderly witness to the Nakba, the violent 1948 expulsion of native Palestinians from Israel—but to their surprise, the survivor doesn’t want to rehash his trauma for the media.

Who it’s for: Anyone looking insight—tinged with grim humor—into the years leading up to the present political crisis in the Middle East and the decades-long goal of Palestinian autonomy. —NodB

The Shutouts by Gabrielle Korn [F]

What it's about: In the dystopian future, mysteriously connected women fight to survive on the margins of society amid worsening climate collapse.

Who it's for: Fans of Korn's Yours for the Taking, which takes place in the same universe; readers of Becky Chambers and queer-inflected sci-fi. —SMS

What in Me Is Dark by Orlando Reade [NF]

What it's about: The enduring, evolving influence of Milton's Paradise Lost on political history—and particularly on the work of 12 revolutionary readers, including Malcom X and Hannah Arendt.

Who it's for: English majors and fans of Ryan Ruby and Sarah Bakewell—but I repeat myself. —SMS

The Afterlife Is Letting Go by Brandon Shimoda [NF]

What it's about: Shimoda researches the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during WWII, and speaks with descendants of those imprisoned, for this essay collection about the “afterlife” of cruelty and xenophobia in the U.S.

Who it’s for: Anyone to ever visit a monument, museum, or designated site of hallowed ground where traumatic events have taken place. —NodB

No Place to Bury the Dead by Karina Sainz Borgo, tr. Elizabeth Bryer [F]

What it's about: When Angustias Romero loses both her children while fleeing a mysterious disease in her unnamed Latin American country, she finds herself in a surreal, purgatorial borderland where she's soon caught in a power struggle.

Who it's for: Fans of Maríana Enriquez and Mohsin Hamid. —SMS

The Rest Is Silence by Augusto Monterroso, tr. Aaron Kerner [F]

What it is: The author of some of the shortest, and tightest, stories in Latin American literature goes long with a metafictional skewering of literary criticism in his only novel.

Who it's for: Anyone who prefers the term "palm-of-the-hand stories" to "flash fiction." —JHM

Tali Girls by Siamak Herawi, tr. Sara Khalili [F]

What it is: An intimate, harrowing, and vital look at the lives of girls and women in an Afghan mountain village under Taliban rule, based on true stories.

Who it's for: Readers of Nadia Hashimi, Akwaeke Emezi, and Maria Stepanova. —SMS

Sun City by Tove Jansson, tr. Thomas Teal [F]

What it's about: During her travels through the U.S. in the 1970s, Jansson became interested in the retirement home as a peculiarly American institution—here, she imagines the tightly knit community within one of them.

Who it's for: Fans of Jansson's other fiction for adults, much of which explores the lives of elderly folks; anyone who watched that documentary about The Villages in Florida. —SMS

Editor's note: We're always looking to make our seasonal book previews more useful to the readers, writers, and critics they're meant to serve. Got an idea for how we can improve our coverage? Tell me about it at sophia@themillions.com.

[millions_email]

Memorizing and Memory: A Writer’s Estranged Cousins

1. Memorizing

My lines disappeared. I was in 10th grade, dressed in a blue-checked gingham dress and white tights, playing the lead in Alice and Wonderland for an audience of children. I’d had memory lapses before—an embarrassing one in my piano teacher’s living room in fifth grade, the specific, awkward misery of having to begin the sonatina again. The assembled families either would or would not pretend it didn’t happen, both options mortifying. I lost my lines in ninth grade as well, playing Lucy in You’re a Good Man Charlie Brown. I was mid-song when the words atomized, but I belted out something anyway; I don’t know what. Whatever happened that time left me unscathed.

In general, however, no memory lapses. Not at the sixth-grade safety assembly run by a cop who held up a license plate. When he quizzed 500 of us seated on the gymnasium floor 10 minutes later, I was the only one who could recite the numbers. I’d memorized them from boredom. No problems either when I played Eliza in My Fair Lady the summer after seventh grade.

Alice in Wonderland was different. I stopped trusting my memory. Betrayed at age 14, I lost faith that anything would ever stick again. I saw my inability to memorize as a terrible weakness, and it haunted me.

Years of viola study followed. I got to the point where I could identify most any piece on any classical radio station. It takes practice, but it’s not exactly memorizing; composers leave tracks as clearly as deer crossing a snowy field. You get to know a composer’s output—Johannes Brahms left us only four symphonies (he destroyed more); César Franck wrote one piano quintet. Composers’ nationalities become as recognizable as flags. If a piano quintet sounds French, and/or has phrases that mirror those in César Franck’s Symphony in D Minor, it’s not too hard to narrow it to the right piece. And once you’ve played or performed a composition, it stays with you as surely as remembering how to walk.

To me this is uninspiring; more akin to reciting the times tables than interrogating music’s mysteries. Much more meaningful are the memories that accompany first hearing or first playing:

I’m 16, on the edge of a metal folding chair, heart palpitating, listening to five students playing in a rehearsal room too small to contain the sound. At a music camp in Orono, Maine, I’m hearing the Brahms Piano Quintet in F Minor for the first time. I’m in an adrenaline-fueled high; I’m a jockey on a winning horse.

I’m at my music stand in the living room of a math professor from M.I.T. with whom I played chamber music, weeping that I have lived in ignorance of the third movement to the Schumann Piano Quartet in E Flat Major. The sound covers me like a hot blanket of grief, first the violin and the cello and then my part! The viola gets that heartbreaking melody, the one that sings to the world’s beauty slipping away, to the impermanence of love and life.

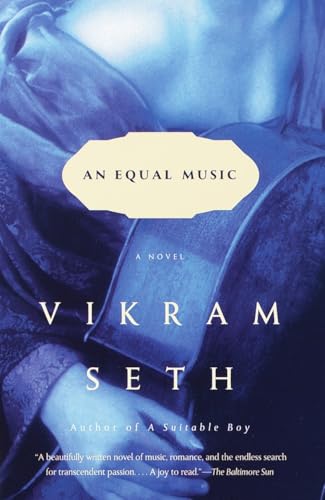

I don’t care if I sound hyperbolic; that’s what I felt. I’m not so different with books. Ask me whether I’ve read a certain book or a certain author, what it’s about, when I read it, who recommended it to me, and I’ll answer. But aren’t those memories somewhat meaningless? I’d rather share the feeling I had—the breathtaking experience of reading Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse for the first time, of being unable to contain my excitement about Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God, of rushing to complete Robertson Davies’s trilogies; the deep serenity of living with May Sarton for months on end, and the connection I felt with Vikram Seth’s An Equal Music.

For a career in classical music, recognizing any piece won’t cut it. Books, of course, are beside the point. To become a professional violist, you must memorize; you have to be able to take an audition without sheet music, an ability I lost at age 14.

And yet, I entered college with the aspiration of becoming a professional musician. For a year or two during that time, I studied with a viola teacher who tried to cure me of my memorizing deficit. Our lessons were in his apartment on New York’s Upper West Side where he lived in an Old World space, dimly lit with lamps that must have come from Vienna in the 1930’s, walls lined with sheet music, and floors laid out in imported Persian rugs. He recommended I study the ads on New York City buses and memorize the numbers or words I found in them. Also, I should note and memorize the numbers on the rear of city buses.

Ultimately, I broke down and left music. My departure was, to my mind, an epic failure; my inability to memorize one of the many reasons for my defeat.

2. Memory

My mother died when I was in my early 40s. Her death was sudden and shocking—a diagnosis of pancreatic cancer for a strong athletic woman who had never been sick. She was gone in the space of eight weeks.

In ways I don’t fully understand, her death unloosed my writing. Granted, my relationship with mom was intimately tied up with books and the written word. She worked as a copy editor and editor. We shared a great interest in reading. Granted too, that I had been writing all along, if writing means keeping a journal and sending snail mail after it went the way of the telegram. Or writing memos at work. And inhaling books. But writing—the kind where you make a commitment and stick to it, where you attempt to take yourself seriously—didn’t come until after mom died.

It was then that I uncovered something altogether different from my memorized files of books and musical compositions. I discovered a trove of personal memories that went back to at least age three. Or more accurately, I found I could access those memories, which I began to appreciate as a generous gift from the writing gods. Memory is a writer’s nutrition and sustenance, her sine qua non.

The cabinets of memory I discovered after mom died were not remotely orderly. Stashed with my memories were other people’s recollections, memories that others had forgotten but I retained. Memories that were crammed into file folders, pieces torn off and gone missing, others like so many balled-up drafts. There were minute details about my siblings, granular information about school lives, friends and frenemies, secrets and intimacies. Don’t ask me to recite a poem. If, on the other hand, you want to know the name of my sister’s fifth grade teacher and what poems this terror of a teacher made her memorize, I’m on it.

I found myself mucking around in exhaustive details about my parents’ jobs; their friends’ careers, marriages, and children. Questions began arising in droves. Why did my father talk more about work than his emotional life? Why did my mother shy away from friendships with women? Random gossip from my early employment reared up and insisted on reinterpretation, indiscretions ranging from salacious to violent; memories that in the time of #MeToo would sink more than a few professional careers.

Writing, I quickly discovered, doesn’t thrive on memorization. And memories that are free from doubt, anxiety, and pain are nearly useless. Writing thrives on conflict and those irreconcilable, problematic memories. Were my overstuffed memory files a cause or symptom of my efforts to write in earnest? Perhaps both.

[millions_ad]

My father died last spring. With his death, I find myself slogging through memories too large to manage. They’re not so much painful, as awkward and uncomfortable. They keep me up at night, in part because so many of those memories are not mine. I hear dad recounting stories about his friends and colleagues, but fewer about himself.

Like mom, my father was a creature of the written word, a highly skilled wordsmith, author of two books and countless articles on varied subjects both personal and professional (he was a trial lawyer). He was the second of four children. His mother lost most of her hearing during his birth. To that physical disability he credited his clear speaking voice, which became stentorian in the courtroom. That does not, however, account for his vast vocabulary—an endless cache of words. Dad’s parents were extraordinarily intelligent, but his mother had a sixth-grade education and his father never finished high school.

Oh, but daddy could speak. His words are emblazoned on my memory. They land on the pages I write—ubiquitous, textured, yet not easy to digest. Does anyone use the word obliterate anymore? Does anyone ablute when entering the shower? I doubt wifty is even a word.

Words came tumbling out of my father, huge ones, short ones, fat ones, skinny ones. He was a stickler for precision. He kept a huge dictionary behind his chair at the dining room table. If we weren’t sure of a word’s definition, he would dive into the book and demand, “Will you accept Webster’s Unabridged as a source?” He never read one of my junior high school social studies papers that he didn’t thoroughly mark up, because words matter and it’s always possible to be more precise.

Words are memories, but they are tools too, carving out bits of text from the lumpy rind of the past. It’s a daily effort—often exhausting—to try to keep the commotion of family memories at bay while simultaneously holding onto those noisy recollections.

I see now that I’m lucky for my memory, however unruly and ill-behaved it is. I mine it every time I put pen to paper. It is brine for my writing, even if I’ll never fully understand it. Wading through the chaos, I’ve learned that memory is more useful than memorizing. I might even forgive myself that shortcoming. I’m beginning to realize memorizing is too far removed from memory to qualify as even a distant relative.

[millions_email]

Image credit: Unsplash/Siora Photography.

A Year in Reading: Nick Moran

Two years ago I moved from Hoboken to Baltimore and I marked the occasion in the typical fashion: by pledging to read books only set in, connected to, or written by authors from the state of Florida. My rationale and the precise reasons for its timing elude me to this day. I didn’t think much of it; it simply felt natural. Maybe it had something to do with my relocation occurring during the winter, when the northern air thins out and becomes painful enough to make me crave the amniotic coat of tropical humidity. Perhaps it's explained as psycho-geographic regression. The places I’ve inhabited longest are New Jersey and Florida, and if I was definitely leaving one to settle someplace new, then I suppose it’s natural to yearn for the comforts of the other home I know best. Hell, it might’ve been because I was three years out of college and I missed Miami. Who can really say? Who cares? The short of it is: I made my decision, and I moved forward.

What followed was equal parts overwhelming, disorienting, and hallucinatory. That much Florida does a man no good - and that’s doubly true when the man in question lacks any semblance of restraint. See, I wasn’t content to make a structured list and to steadily chip away at it. On the contrary, what I desired most was total immersion, or better yet submergence. So deep ran the currents of my obsession that at one point I set up Google alerts pairing the word “Florida” with random nouns. (You don’t appreciate the depth of Florida’s strangeness until one day you get two different news stories detailing pork chop-related violence: Exhibit A, Exhibit B.)

In two years, I made my way across the foundation of Florida writing: Marjory Stoneman Douglas’s River of Grass and Peter Matthiessen’s Shadow Country; Michael Grunwald’s The Swamp, John McPhee's Oranges, and Arva Moore Parks’s Miami; Pat Frank’s Alas, Babylon, and Denis Johnson’s Fiskadoro. (More on those over here.) I reread Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God, and I dipped into poetry by Campbell McGrath, Elizabeth Bishop, Richard Blanco, and Donald Justice. Mia Leonin dazzled me and Alissa Nutting creeped me out. With increasingly deep breaths, I inhaled Carl Hiaasen’s entire God damned oeuvre until I felt like I was having a psychic asthma attack.

That didn't quite scratch the itch, though, so I supplemented my reading with other art forms as well. It began last winter when I fell asleep reading Joy Williams's Florida Keys guide and had what I thought was a lucid dream about Islamorada, but was really just the beginning of a Bloodline episode playing as I woke up. I spent the next week plowing through the series. I followed Florida Man and Florida Woman on Twitter. I favorited more Craig Pittman tweets than I can count. I revisited Ace Ventura and There's Something About Mary. I watched the Billy Corben triumvirate of Cocaine Cowboys, Dawg Fight, and The U, and I celebrated the premier of The U Part 2 by getting drunk off Jai Alai that I'd bulk ordered across state lines from a liquor store in Dunedin. I tried to watch Ballers but that thing's like an even less deeply plotted Entourage, so...yeah. Meanwhile, I'll never be ashamed of how much DJ Laz and Trick Daddy I've played. (Before anyone asks: Yes, I have donated to the latter's Trickstarter.)

I watched both Magic Mike movies because nothing's more quintessentially Tampa than the scene in the first one in which Channing Tatum scolds "Adam" for peeling off the protective plastic wrapper on his pick-up truck's dashboard, which would totally kill the thing's resale value. I read long, multi-part investigative news stories on widespread ecological destruction, for-profit college fraud, and government corruption. I contemplated buying prints from The Highwaymen and Clyde Butcher, but didn't have the bankroll to go through with it.

Throughout this process, I've taken notes. To some extent, this was automatic. It's something I've always done as I've read. It's how I write, really: read first, take notes, and ideas for written work will follow. For this project, however, the Florida canon has become too big. Wrangling these disparate pieces would be like trying to limit the number of pythons invading the Everglades. It can't be done.

Instead, I'm left with an unmanageable list of tidbits, direct quotations, and half-remembered ephemera lacking any semblance of a theme beyond their essential "Florida-ness." Whereas on smaller projects my notes could serve as navigational buoys capable of guiding me back to an overall idea, these manic, unorganized Florida notes are what would happen if Hansel & Gretel threw their bread crumbs into a woodchipper. To wit, here are the six latest entries I've saved in my 1,700 row Excel document:

40% of dogs who shoot people live in Florida. (Source)

"A Miami suburb has been named as the 'bidet capital of America'" (Source)

"Dead woman's life insurance funding husband's murder defense." (Source)

"Florida man bit by shark catches shark, says he will eat it." (Source)

"Cop fired for singing about killing with death-metal band." (Source)

"How is Hendry County going to know how to handle massive monkey escapes during a hurricane?” (Source)

Where does the rabbit hole end? Is it possible to prismatically marry all of these disparate rays of weirdness into a single, unified beam?

This is all to say: for two years now, I’ve been steeped in Florida.

Of course, as with every rule, it was broken from time to time. Or, I should say, I tried to break it. As anyone who’s driven on a highway can tell you: once you notice one type of car, it’s all you’ll see thereafter. Reading works outside my Florida canon almost always meant I’d identify an unexpected Florida connection in the process. When I read Marlon James’s remarkable novel A Brief History of Seven Killings, I encountered what is certainly the only mention of Miramar to have ever been awarded the Booker prize. When I read City on Fire, Garth Risk Hallberg’s massive, hyper-localized depiction of New York City, one of the details that stuck out most was a throwaway passage about one character’s estranged daughter living in…well, where do you think?

More unsettling still: it's often felt like Florida is the one seeking me out, or beckoning me from afar. (And I'm not talking about my alma mater's alumni office calling for donations.) Maybe all of Florida is Area X. Indeed, this siren's song can transverse spacetime. Imagine my surprise when I first watched Drake's "Hotline Bling" video -- a video so devoid of geographic setting that it takes place in a series of sterilized geometric patterns -- and still find myself cognizant of the work's Florida influence. Seriously, read this.

Truly, my year in reading has been two years in Florida, and as I look beyond to the years ahead, I see no reason to stop. Maybe I can't. Maybe the essence of Florida inhabits me like one of the invasive species that's inhabited it. There was an article this year about how scientists are baffled by a type of creeping, foreign mangrove invading Florida's swamps -- this colonizing plant to which sediments cling, muck becomes coated, and upon which land eventually forms. Nobody can explain the way the plants are acting, the way they're resisting efforts to contain their spread. They are the essence of Florida, though: all that persistence, all that infestation.

Ultimately, the spirit of the Year in Reading series necessitates that I provide you all with specific titles to check out, and to fulfill that obligation, my choice is easy: the best book I read this year was Jennine Capó Crucet's debut collection of stories, How to Leave Hialeah. In it, Crucet explores the variety of experience around the Miami metropolitan area and amongst its residents -- its real residents; not the tourists, not the northeastern college kids who treat their stints at the University of Miami like a four-year Spring Break, and especially not the absentee condominium owners who’ve been driving up the city’s rents for years. No. Crucet grounds her stories within the mostly Cuban diaspora living in Hialeah and its surrounding environs: the community that, along with Miami’s extremely under-appreciated African-American and Afro-Caribbean residents, comprises the city’s beating heart -- the ones who give South Florida an identity immediately distinct from that of anywhere else in the state, or really anywhere else in America.

In 11 stories, Crucet covers a remarkable amount of South Florida's characteristic breadth: the Ecstasy-rolling girl seeking after-hours ablution (and Celia Cruz) in a church, the family politics of Nochebuena invites, the man who died in a Chili's-related incident and left his roommate to deal with his pet ferret, and the children who find a body in a canal. She renders the complicated in-betweenness of immigrants straddling the Florida Straits between Cuba and their adopted homes, and how the younger generation oscillates between ambivalence and passion for the same. She examines these characters and their predicaments with closely-observed, generous authenticity, utilizing the vocabulary of their setting all the while: people's hands and faces are said to be "the color of dried palm fronds;" a family's closeness is described as being "like the heat in a car you've left parked in the sun;" a woman on the beach observes the way her date "leaned back on his elbows again, his nipples spreading away from each other, melting across his chest toward the pockets of his armpits." These are moving, visceral glimpses at the myriad Miamis and Miamians. Even if you've never set foot down here, they're not to be missed.

The collection's title story -- and also its last -- tracks a young woman's early life in semi-autobiographical detail as she's raised in Hialeah, moves on to out-of-state college, and advances into a career beyond. It looks to the possibilities of a life outside of the one you know first, and it evokes a sense of wonder at the world beyond Florida. It also -- and, by now you can tell I relate -- makes clear that no matter how far away you go, you'll never really leave it behind.

More from A Year in Reading 2015

Don't miss: A Year in Reading 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005

The good stuff: The Millions' Notable articles

The motherlode: The Millions' Books and Reviews

Like what you see? Learn about 5 insanely easy ways to Support The Millions, and follow The Millions on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr.

Zora Neale and My Sister

1.

Over the two week period when I finalized my plans for a trip to my home state of Alabama, I went from sunny optimism about the trip to downright depression. My visit had two purposes. One was to visit Notasulga, the birthplace of one of my favorite authors, Harlem Renaissance writer Zora Neale Hurston (the source of my optimism) and the second was to spend a little time with my sister...

Less than a year earlier on another trip down to Alabama I had participated in my sister’s wedding, where there were plenty of side conversations with relatives and friends at the reception in the small church hall about how Debra, emaciated by the ravages of colon cancer less than a decade earlier, was now a pretty, slightly plump bride.

By the time I arrived in Alabama the second time, most of the relatives knew as I did: the cancer had returned. We didn’t learn any of this from Debra. “I’m doing fine,” she always said whenever we talked by phone and my probing questions about when she had seen the doctor last or what the doctor had said during a last visit got me anywhere. Our mother was still in her long recovery from brain surgery so my niece (Debra’s only child) was my only lifeline to the truth. My niece was with Debra when I arrived at the hospital in Tuscaloosa.

Although I had been warned that Debra had lost a lot of weight, the sight of her lying in the hospital bed, her narrow face staring at me through metal rimmed glasses I had never seen her wear before, sent my body into immediate rebellion. I felt as though it was trying to forge some reaction from me, but not yet sure what it was, I didn’t know whether to fight or give in. The best I could do was manage a boyish grin, the same one I had probably brandished when I had surprised her by showing up at her wedding rehearsal eight months earlier.

“Pull up a seat,” Debra said, sounding much more robust than she looked. She pointed at a metal chair shoved against the wall near the door to the small bathroom. I reached for the chair feeling her studying me in that way big sisters do and feeling the panic I felt years earlier when I first heard the news from my mother that Debra had colon cancer.

I was surprised at how easily the chair lifted, like it was made of some newly discovered lightweight metal with titanium-mitered joints. Where was the science to help my sister?

Before sitting down near her bed I leaned over and kissed Debra’s forehead. Her dry skin was a surprise from the moist ninety degree air that had soaked my neck and arms on the short walk up from the sweltering underground parking lot. “You’re as skinny as me,” Debra said, looking up at me over the rim of her glasses. “What’s your excuse?”

As we talked, I wanted to ask about her husband, a man she had known for years before she married him, but I had heard the relationship had been strained lately and I didn’t want to upset her. We talked until the nurse came in and began busying himself around the bed. On the walk outside to the elevator, my niece and I talked about how hard it was to accept Debra’s decision to take a break from chemotherapy. Debra’s doctor had advised investigative surgery to find out what was causing her inability to digest food. “She refuses to do the surgery,” my niece said, her voice sounding like she was struggling to remain calm.

The news came just as a crowd exited the elevator. My niece and I remained quiet as the crowd passed. I knew that once Debra’s mind was made up about a matter, there was little chance of changing it. I suspected my niece knew that too. “The doctor says she can go home today,” I reminded my niece. “That’s a good sign. I’ll talk to her when I return tomorrow evening.”

2.

On the highway later during most of the two hour drive, I worried about my next visit with Debra, It had never occurred to me to imagine a world in which my sister was not alive. As adults we had grown apart with brief visits during the rare trips I made back to Alabama to attend funerals, including the funeral of Debra’s son who drowned when he was barely twenty. Now I began to consider death as a real possibility.

Soon my optimism about my first trip to Notasulga, in which I imagined myself an investigative journalist, evaporated into hard fatalism. This was not the state of mind I imagined myself to be in the summer before at the Norman Mailer Center where I had greedily soaked up the interview techniques that I imagined star reporters use: develop a good list of questions before hand, tape as many interviews as you can, start with the easy questions. This is going to be a fiasco, I told myself a few miles outside Montgomery.

I became interested in Zora Neale Hurston after reading about other early 20th century literary figures like the poet Langston Hughes, the editor Alaine Locke and the novelist Nella Larsen. Hurston’s name appeared in articles about Harlem Renaissance writers, but I paid her name passing notice until I learned that she had been born in Alabama. I later realized that Zora Neale and I had more than that in common. We both spent time in the Washington D.C. area, both lived and wrote in Harlem, both studied at Columbia University. Until then the only writers that readily came to mind with ties to Alabama were Harper Lee and Truman Capote. Both had produced captivating works. Perhaps Zora Neale had too.

Half an hour on the other side of Montgomery, I exited the highway, beginning to imagine that my quest to visit Hurston’s birthplace seemed silly. Yes, Hurston was born in Notasulga, but her family moved away when she was still a toddler. Did she even remember living in the town? Moreover, throughout her life Hurston claimed she was born in Eatonville, Florida. I understood the enticement: Eatonville touts itself as the first town in America incorporated by African Americans. Hurston’s father served several terms as mayor.

Notasulga is no Eatonville. With barely nine hundred residents within sixteen square miles, the hamlet sits a short drive from Tuskegee and Montgomery which offer museums to Tuskegee Institute founder Booker T. Washington, civil rights pioneer Rosa Parks, even Hurston’s literary contemporaries F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald. The important role Notasulga played in Hurston’s literary career became apparent to me after reading her first novel. Though Hurston had early success with stories set in Florida, it was the critical and commercial success of Jonah’s Gourd Vine that catapulted her from a talented but unknown writer to a commercially successful one. Many of Hurston’s important early critics and readers first came to her writing immersed in the setting of Notasulga.

The Wednesday afternoon in June I arrived, downtown Notasulga -- several blocks of low buildings running in several directions from a two-bulb-traffic light -- had the quiet feel of a small town on a Sunday. The only enterprises that looked open were Hughes Auto Parts, Ben’s Bargains, Citizen’s Hardware and Supply and Town Hall. On the main corner, I walked through the white pillars at the entrance of Town Hall wondering if anyone inside had heard of Zora Neale. Hurston left the area over a century earlier in 1894, but she returned to the south many times. In 1927, she and fellow Harlem Renaissance writer Langston Hughes spoke to summer students at Tuskegee Institute, and in nearby Mobile, Hurston, interviewed Cudjo Lewis, the man believed to have been the lone surviving passenger of the last slave trip to land in the U.S. On other trips, Hurston collected the folktales, character sketches, and historical artifacts that informed her four novels, her autobiography, scores of plays, essays, and her many short stories.

What intrigued me most about Hurston as I read more of her work was her success at telling stories about African Americans living in the south that resonated with readers no matter what their background. I was familiar with Hurston’s most famous work, Their Eyes Were Watching God, published in 1937, but I was surprised to learn of the critical praise heaped on her first novel. Carl Sandburg, among others, praised Hurston’s debut as “A bold and beautiful book, many a page priceless and unforgettable.” The novel’s title alludes to the biblical story of Jonah, who during his travels to preach in a foreign land, is swallowed by a whale. After deliverance from the whale’s belly, Jonah reaches his destination angry and frustrated at God’s refusal to punish those who had sinned. As Jonah watches the city from a place to the east, a divine gourd plant grows over his head and provides shade. But later, a worm attacks the plant and it withers. Under a burning wind and searing sun, Jonah becomes faint and eventually says, “I would be better off dead than alive.”

Before this trip to Alabama, I had a vague notion of what manner of suffering might make a person accept death. But seeing my sister in the hospital bed, surrounded by overturned pill cups and hanging feeding tubes and buzzing wall devices -- witnessing the frail remains of what had once been a vibrant healthy-looking body -- though I still did not want her to refuse the operation, I began to understand how her suffering might have opened her up to such fatalistic thoughts.

Hurston herself suffered a variety of health maladies before she died in 1960. And though the publication of Jonah’s Gourd Vine initiated a decade-long period of critical and commercial success for Hurston, after she published her last book Seraph on the Sewanee in 1948, her literary reputation waned. By the time she died, publishers and readers had lost interest in her work. Inside Notasulga Town Hall, the elderly clerk at the counter gave me a puzzled look when I mentioned Zora Neale. She also gave me my first piece of bad news: “The town records burned twice,” she said, sounding sorry to be delivering the news. “You might try the county seat.”

Which county? I wondered outside as I stood on a small bridge at the edge of the business district looking east toward the county line. Most of Notasulga sits in Macon County but a small north-east corner lies in Lee County. Hurston’s father was born in Lee County in 1861, the year Alabama seceded from the Union. Zora Neale used to say that the area had an abundance of creeks, but below the small bridge were only railroad tracks, a reminder of the post-Civil War period when Notasulga was a whistle stop on the rail line than ran from Montgomery then east toward Opelika and the Georgia border. Photographs from the period show a post office, express office, and cotton gin. In addition to cotton, local farmers also marketed rice, tobacco, soy beans, sweet potatoes, and peanuts.

Jonah’s Gourd Vine opens with the protagonist, John “Buddy” Pearson under threat of being “bound over” to one of the Reconstruction-era plantations, to toil there under conditions little better than those offered during legally enforced slavery. Pearson is not yet twenty when his step-father announces the news. His mother, unable to reverse her husband’s decision, decides to send their son into Notasulga to seek work at a farm that she hopes has better working conditions.

Much of the novel is autobiographical, and John Pearson’s yearnings -- like those of Hurston’s own father-- eventually lead him to Florida where he becomes an influential preacher and community leader. But first, Pearson has to face the challenges of being driven out of his home in Alabama. On the plantations and lumber camps where he finds work, he has strained relationships with the first of many jealous men and inviting women he encounters often over the course of the novel. He also courts a local girl named Lucy Potts by attending Macedonia Baptist Church.

The original Macedonia Baptist Church no longer exists, replaced by a stately red brick building along the highway just outside of downtown. I wandered the grounds in a fruitless attempt to find remnants of the old school house that might have been on the property. Half a mile down the road were the Spanish-style buildings on the campus of Notasulga High School, but those buildings were constructed by WPA workers in the 1930s for white students. Farther south, the Rosenwald School, financed by Julius Rosenwald, the head of Sears and Roebuck, to educate black students, was not built until the early 1900s. The schoolhouse that inspired the early scenes in Jonah’s Gourd Vine was probably one of the first schools built in the south to educate recently freed African American children.

3.

After multiple trips down a few side roads in Lee County, I fumbled my way through several interviews of people from the town. Yet, the main interview I was looking forward to seemed to be slipping away from me as soon as it started. I sat down with Mary Potts-Travis inside a small hair salon not far from the picturesque town square in Tuskegee. Mary was a small woman with drawn-in shoulders and a thin face. She had a strong profile, the bearing of someone who might have been a professor or an engineer had she been born a century later. She wore a plastic smock over a simple dress. Less than a minute after I started my questions, Mary looked at me with heavy concern and said: “Young man, I have no idea what in the world you’re asking. What is it that you want?”

In the midst of fear and panic I reverted to the one tactic I remembered from my seminar: “What is your earliest memory of Notasulga?” I said quite tentatively. That seemed to do the trick. Mary, who I had been told might be a distant relative of Zora, said she had been born in Notasulga ninety-one years earlier when there was a single grocery store that sold shoes and hats and eggs and ground corn in the back. She recalled a clothing store, and a woman who sold Nehi sodas out of her house. She described the cotton farmers and the bankers and the two-room school in the church yard. I was still scribbling furiously nearly an hour later when the salon’s manager walked over and informed Mary it was time for her appointment.

Whatever bit of confidence I had garnered from salvaging my interview of Mary deflated when, at the records’ office in Tuskegee, I asked the clerk how I might find out when the Potts had purchased their land, and who owns it now. “Give it up,” the clerk said, but still directed me to a musty side room crowded with stacks of enormous leather-covered record books. “The records are probably not here.”

Addled from several fruitless hours turning hundreds of yellowed pages, I later drove past the Potts homestead several times before realizing it. In the novel, Lucy’s parents (like Hurston’s maternal grandparents) are one of very few land-owning families in Macon County and strongly opposed their daughter marrying the uneducated and landless John Pearson. During his first visit to Lucy’s home, John Pearson notices the “Flowers in the yard among whitewashed rocks. Tobacco hanging up to dry. Peanuts drying on white cloth in the sun. A smokehouse, a spring-house, a swing under a china-berry tree, bucket flowers on the porch.”

The place I had been told was the Potts homestead presented a more modest face the day I visited. A patchy yard surrounded the yellow clapboard house, which was trimmed in brown. I walked to the back yard later, unable to separate the real Lucy Potts presented in Hurston’s autobiography from the Lucy Potts in Jonah’s Gourd Vine. Both Lucys got dressed on their wedding days unsure if any family members would accompany them from the house to the church. Both Lucys later suffered a challenging marriage. And both Lucys died relatively young.

The backyard, overgrown with tall weeds and thick vines, was more evocative of the two Johns whose metaphorical vines continued to grow after they moved their families to Florida. Both became popular preachers and community leaders, but eventually both their vines withered. In the novel, John Pearson’s metaphorical vine is eaten away by many worms: the wrath of jealous men, the problems of chasing women, his own hubris, and especially his grief over the death of Lucy. Late in the novel when adultery charges threaten to destroy John Pearson’s new marriage and his standing in the community, he finds solace in resurrecting memories of Lucy and Notasulga:

So John sat heavily in his seat and thought about that other time nearly thirty years before when he had sat handcuffed in Cy Perkin’s office in Alabama. No fiery little Lucy here, thrusting her frailty between him and trouble. No sun of love to rise upon a gray world of hate and indifference.

I left the Potts homestead deciding to make more visits to Notasulga, and to learn more about the town that Hurston had mined to fashion an enduring love story. The road from the Potts homestead winds past nice houses next to dilapidated ones, reminders of the economic disparities that threatened that long ago courtship and marriage that was not without its challenges.

Love, I suspect -- or at least companionship — sustained my sister during her initial round of therapies and doctor visits after the return of her cancer. The next morning, before leaving my hotel along the highway outside Montgomery, I dialed my sister’s number, remembering how happy she was the day of her wedding. Her relationship had gotten rocky since, but I had heard that she and her husband were working at it. “Yes, I’m back at home,” Debra said, her voice hoarse but slightly cheery, when she answered the phone. “Of course, I’m up for another visit. I feel fine.”

Image courtesy the author