Mentioned in:

Most Anticipated: The Great Spring 2024 Preview

April

April 2

Women! In! Peril! by Jessie Ren Marshall [F]

For starters, excellent title. This debut short story collection from playwright Marshall spans sex bots and space colonists, wives and divorcées, prodding at the many meanings of womanhood. Short story master Deesha Philyaw, also taken by the book's title, calls this one "incisive! Provocative! And utterly satisfying!" —Sophia M. Stewart

The Audacity by Ryan Chapman [F]

This sophomore effort, after the darkly sublime absurdity of Riots I have Known, trades in the prison industrial complex for the Silicon Valley scam. Chapman has a sharp eye and a sharper wit, and a book billed as a "bracing satire about the implosion of a Theranos-like company, a collapsing marriage, and a billionaires’ 'philanthropy summit'" promises some good, hard laughs—however bitter they may be—at the expense of the über-rich. —John H. Maher

The Obscene Bird of Night by José Donoso, tr. Leonard Mades [F]

I first learned about this book from an essay in this publication by Zachary Issenberg, who alternatively calls it Donoso's "masterpiece," "a perfect novel," and "the crowning achievement of the gothic horror genre." He recommends going into the book without knowing too much, but describes it as "a story assembled from the gossip of society’s highs and lows, which revolves and blurs into a series of interlinked nightmares in which people lose their memory, their sex, or even their literal organs." —SMS

Globetrotting ed. Duncan Minshull [NF]

I'm a big walker, so I won't be able to resist this assemblage of 50 writers—including Edith Wharton, Katharine Mansfield, Helen Garner, and D.H. Lawrence—recounting their various journeys by foot, edited by Minshull, the noted walker-writer-anthologist behind The Vintage Book of Walking (2000) and Where My Feet Fall (2022). —SMS

All Things Are Too Small by Becca Rothfeld [NF]

Hieronymus Bosch, eat your heart out! The debut book from Rothfeld, nonfiction book critic at the Washington Post, celebrates our appetite for excess in all its material, erotic, and gluttonous glory. Covering such disparate subjects from decluttering to David Cronenberg, Rothfeld looks at the dire cultural—and personal—consequences that come with adopting a minimalist sensibility and denying ourselves pleasure. —Daniella Fishman

A Good Happy Girl by Marissa Higgins [F]

Higgins, a regular contributor here at The Millions, debuts with a novel of a young woman who is drawn into an intense and all-consuming emotional and sexual relationship with a married lesbian couple. Halle Butler heaps on the praise for this one: “Sometimes I could not believe how easily this book moved from gross-out sadism into genuine sympathy. Totally surprising, totally compelling. I loved it.” —SMS

City Limits by Megan Kimble [NF]

As a Los Angeleno who is steadily working my way through The Power Broker, this in-depth investigation into the nation's freeways really calls to me. (Did you know Robert Moses couldn't drive?) Kimble channels Caro by locating the human drama behind freeways and failures of urban planning. —SMS

We Loved It All by Lydia Millet [NF]

Planet Earth is a pretty awesome place to be a human, with its beaches and mountains, sunsets and birdsong, creatures great and small. Millet, a creative director at the Center for Biological Diversity in Tucson, infuses her novels with climate grief and cautions against extinction, and in this nonfiction meditation, she makes a case for a more harmonious coexistence between our species and everybody else in the natural world. If a nostalgic note of “Auld Lang Syne” trembles in Millet’s title, her personal anecdotes and public examples call for meaningful environmental action from local to global levels. —Nathalie op de Beeck

Like Love by Maggie Nelson [NF]

The new book from Nelson, one of the most towering public intellectuals alive today, collects 20 years of her work—including essays, profiles, and reviews—that cover disparate subjects, from Prince and Kara Walker to motherhood and queerness. For my fellow Bluets heads, this will be essential reading. —SMS

Traces of Enayat by Iman Mersal, tr. Robin Moger [NF]

Mersal, one of the preeminent poets of the Arabic-speaking world, recovers the life, work, and legacy of the late Egyptian writer Enayat al-Zayyat in this biographical detective story. Mapping the psyche of al-Zayyat, who died by suicide in 1963, alongside her own, Mersal blends literary mystery and memoir to produce a wholly original portrait of two women writers. —SMS

The Letters of Emily Dickinson ed. Cristanne Miller and Domhnall Mitchell [NF]

The letters of Emily Dickinson, one of the greatest and most beguiling of American poets, are collected here for the first time in nearly 60 years. Her correspondence not only gives access to her inner life and social world, but reveal her to be quite the prose stylist. "In these letters," says Jericho Brown, "we see the life of a genius unfold." Essential reading for any Dickinson fan. —SMS

April 9

Short War by Lily Meyer [F]

The debut novel from Meyer, a critic and translator, reckons with the United States' political intervention in South America through the stories of two generations: a young couple who meet in 1970s Santiago, and their American-born child spending a semester Buenos Aires. Meyer is a sharp writer and thinker, and a great translator from the Spanish; I'm looking forward to her fiction debut. —SMS

There's Going to Be Trouble by Jen Silverman [F]

Silverman's third novel spins a tale of an American woman named Minnow who is drawn into a love affair with a radical French activist—a romance that, unbeknown to her, mirrors a relationship her own draft-dodging father had against the backdrop of the student movements of the 1960s. Teasing out the intersections of passion and politics, There's Going to Be Trouble is "juicy and spirited" and "crackling with excitement," per Jami Attenberg. —SMS

Table for One by Yun Ko-eun, tr. Lizzie Buehler [F]

I thoroughly enjoyed Yun Ko-eun's 2020 eco-thriller The Disaster Tourist, also translated by Buehler, so I'm excited for her new story collection, which promises her characteristic blend of mundanity and surrealism, all in the name of probing—and poking fun—at the isolation and inanity of modern urban life. —SMS

Playboy by Constance Debré, tr. Holly James [NF]

The prequel to the much-lauded Love Me Tender, and the first volume in Debré's autobiographical trilogy, Playboy's incisive vignettes explore the author's decision to abandon her marriage and career and pursue the precarious life of a writer, which she once told Chris Kraus was "a bit like Saint Augustine and his conversion." Virginie Despentes is a fan, so I'll be checking this out. —SMS

Native Nations by Kathleen DuVal [NF]

DuVal's sweeping history of Indigenous North America spans a millennium, beginning with the ancient cities that once covered the continent and ending with Native Americans' continued fight for sovereignty. A study of power, violence, and self-governance, Native Nations is an exciting contribution to a new canon of North American history from an Indigenous perspective, perfect for fans of Ned Blackhawk's The Rediscovery of America. —SMS

Personal Score by Ellen van Neerven [NF]

I’ve always been interested in books that drill down on a specific topic in such a way that we also learn something unexpected about the world around us. Australian writer Van Neerven's sports memoir is so much more than that, as they explore the relationship between sports and race, gender, and sexuality—as well as the paradox of playing a colonialist sport on Indigenous lands. Two Dollar Radio, which is renowned for its edgy list, is publishing this book, so I know it’s going to blow my mind. —Claire Kirch

April 16

The Notebooks of Sonny Rollins by Sonny Rollins [NF]

The musings, recollections, and drawings of jazz legend Sonny Rollins are collected in this compilation of his precious notebooks, which he began keeping in 1959, the start of what would become known as his “Bridge Years,” during which he would practice at all hours on the Williamsburg Bridge. Rollins chronicles everything from his daily routine to reflections on music theory and the philosophical underpinnings of his artistry. An indispensable look into the mind and interior life of one of the most celebrated jazz musicians of all time. —DF

Henry Henry by Allen Bratton [F]

Bratton’s ambitious debut reboots Shakespeare’s Henriad, landing Hal Lancaster, who’s in line to be the 17th Duke of Lancaster, in the alcohol-fueled queer party scene of 2014 London. Hal’s identity as a gay man complicates his aristocratic lineage, and his dalliances with over-the-hill actor Jack Falstaff and promising romance with one Harry Percy, who shares a name with history’s Hotspur, will have English majors keeping score. Don’t expect a rom-com, though. Hal’s fraught relationship with his sexually abusive father, and the fates of two previous gay men from the House of Lancaster, lend gravity to this Bard-inspired take. —NodB

Bitter Water Opera by Nicolette Polek [F]

Graywolf always publishes books that make me gasp in awe and this debut novel, by the author of the entrancing 2020 story collection Imaginary Museums, sounds like it’s going to keep me awake at night as well. It’s a tale about a young woman who’s lost her way and writes a letter to a long-dead ballet dancer—who then visits her, and sets off a string of strange occurrences. —CK

Norma by Sarah Mintz [F]

Mintz's debut novel follows the titular widow as she enjoys her newfound freedom by diving headfirst into her surrounds, both IRL and online. Justin Taylor says, "Three days ago I didn’t know Sarah Mintz existed; now I want to know where the hell she’s been all my reading life. (Canada, apparently.)" —SMS

What Kingdom by Fine Gråbøl, tr. Martin Aitken [F]

A woman in a psychiatric ward dreams of "furniture flickering to life," a "chair that greets you," a "bookshelf that can be thrown on like an apron." This sounds like the moving answer to the otherwise puzzling question, "What if the Kantian concept of ding an sich were a novel?" —JHM

Weird Black Girls by Elwin Cotman [F]

Cotman, the author of three prior collections of speculative short stories, mines the anxieties of Black life across these seven tales, each of them packed with pop culture references and supernatural conceits. Kelly Link calls Cotman's writing "a tonic to ward off drabness and despair." —SMS

Presence by Tracy Cochran [NF]

Last year marked my first earnest attempt at learning to live more mindfully in my day-to-day, so I was thrilled when this book serendipitously found its way into my hands. Cochran, a New York-based meditation teacher and Tibetan Buddhist practitioner of 50 years, delivers 20 psycho-biographical chapters on recognizing the importance of the present, no matter how mundane, frustrating, or fortuitous—because ultimately, she says, the present is all we have. —DF

Committed by Suzanne Scanlon [NF]

Scanlon's memoir uses her own experience of mental illness to explore the enduring trope of the "madwoman," mining the work of Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Virginia Woolf, Sylvia Plath, Audre Lorde, and others for insights into the long literary tradition of women in psychological distress. The blurbers for this one immediately caught my eye, among them Natasha Trethewey, Amina Cain, and Clancy Martin, who compares Scanlon's work here to that of Marguerite Duras. —SMS

Unrooted by Erin Zimmerman [NF]

This science memoir explores Zimmerman's journey to botany, a now endangered field. Interwoven with Zimmerman's experiences as a student and a mother is an impassioned argument for botany's continued relevance and importance against the backdrop of climate change—a perfect read for gardeners, plant lovers, or anyone with an affinity for the natural world. —SMS

April 23

Reboot by Justin Taylor [F]

Extremely online novels, as a rule, have become tiresome. But Taylor has long had a keen eye for subcultural quirks, so it's no surprise that PW's Alan Scherstuhl says that "reading it actually feels like tapping into the internet’s best celeb gossip, fiercest fandom outrages, and wildest conspiratorial rabbit holes." If that's not a recommendation for the Book Twitter–brained reader in you, what is? —JHM

Divided Island by Daniela Tarazona, tr. Lizzie Davis and Kevin Gerry Dunn [F]

A story of multiple personalities and grief in fragments would be an easy sell even without this nod from Álvaro Enrigue: "I don't think that there is now, in Mexico, a literary mind more original than Daniela Tarazona's." More original than Mario Bellatin, or Cristina Rivera Garza? This we've gotta see. —JHM

Prairie, Dresses, Art, Other by Danielle Dutton [NF]

Coffee House Press has for years relished its reputation for publishing “experimental” literature, and this collection of short stories and essays about literature and art and the strangeness of our world is right up there with the rest of Coffee House’s edgiest releases. Don’t be fooled by the simple cover art—Dutton’s work is always formally inventive, refreshingly ambitious, and totally brilliant. —CK

I Just Keep Talking by Nell Irvin Painter [NF]

I first encountered Nell Irvin Painter in graduate school, as I hung out with some Americanists who were her students. Painter was always a dazzling, larger-than-life figure, who just exuded power and brilliance. I am so excited to read this collection of her essays on history, literature, and politics, and how they all intersect. The fact that this collection contains Painter’s artwork is a big bonus. —CK

April 30

Real Americans by Rachel Khong [F]

The latest novel from Khong, the author of Goodbye, Vitamin, explores class dynamics and the illusory American Dream across generations. It starts out with a love affair between an impoverished Chinese American woman from an immigrant family and an East Coast elite from a wealthy family, before moving us along 21 years: 15-year-old Nick knows that his single mother is hiding something that has to do with his biological father and thus, his identity. C Pam Zhang deems this "a book of rare charm," and Andrew Sean Greer calls it "gorgeous, heartfelt, soaring, philosophical and deft." —CK

The Swans of Harlem by Karen Valby [NF]

Huge thanks to Bebe Neuwirth for putting this book on my radar (she calls it "fantastic") with additional gratitude to Margo Jefferson for sealing the deal (she calls it "riveting"). Valby's group biography of five Black ballerinas who forever transformed the art form at the height of the Civil Rights movement uncovers the rich and hidden history of Black ballet, spotlighting the trailblazers who paved the way for the Misty Copelands of the world. —SMS

Appreciation Post by Tara Ward [NF]

Art historian Ward writes toward an art history of Instagram in Appreciation Post, which posits that the app has profoundly shifted our long-established ways of interacting with images. Packed with cultural critique and close reading, the book synthesizes art history, gender studies, and media studies to illuminate the outsize role that images play in all of our lives. —SMS

May

May 7

Bad Seed by Gabriel Carle, tr. Heather Houde [F]

Carle’s English-language debut contains echoes of Denis Johnson’s Jesus’s Son and Mariana Enriquez’s gritty short fiction. This story collection haunting but cheeky, grim but hopeful: a student with HIV tries to avoid temptation while working at a bathhouse; an inebriated friend group witnesses San Juan go up in literal flames; a sexually unfulfilled teen drowns out their impulses by binging TV shows. Puerto Rican writer Luis Negrón calls this “an extraordinary literary debut.” —Liv Albright

The Lady Waiting by Magdalena Zyzak [F]

Zyzak’s sophomore novel is a nail-biting delight. When Viva, a young Polish émigré, has a chance encounter with an enigmatic gallerist named Bobby, Viva’s life takes a cinematic turn. Turns out, Bobby and her husband have a hidden agenda—they plan to steal a Vermeer, with Viva as their accomplice. Further complicating things is the inevitable love triangle that develops among them. Victor LaValle calls this “a superb accomplishment," and Percival Everett says, "This novel pops—cosmopolitan, sexy, and funny." —LA

América del Norte by Nicolás Medina Mora [F]

Pitched as a novel that "blends the Latin American traditions of Roberto Bolaño and Fernanda Melchor with the autofiction of U.S. writers like Ben Lerner and Teju Cole," Mora's debut follows a young member of the Mexican elite as he wrestles with questions of race, politics, geography, and immigration. n+1 co-editor Marco Roth calls Mora "the voice of the NAFTA generation, and much more." —SMS

How It Works Out by Myriam Lacroix [F]

LaCroix's debut novel is the latest in a strong early slate of novels for the Overlook Press in 2024, and follows a lesbian couple as their relationship falls to pieces across a number of possible realities. The increasingly fascinating and troubling potentialities—B-list feminist celebrity, toxic employer-employee tryst, adopting a street urchin, cannibalism as relationship cure—form a compelling image of a complex relationship in multiversal hypotheticals. —JHM

Cinema Love by Jiaming Tang [F]

Ting's debut novel, which spans two continents and three timelines, follows two gay men in rural China—and, later, New York City's Chinatown—who frequent the Workers' Cinema, a movie theater where queer men cruise for love. Robert Jones, Jr. praises this one as "the unforgettable work of a patient master," and Jessamine Chan calls it "not just an extraordinary debut, but a future classic." —SMS

First Love by Lilly Dancyger [NF]

Dancyger's essay collection explores the platonic romances that bloom between female friends, giving those bonds the love-story treatment they deserve. Centering each essay around a formative female friendship, and drawing on everything from Anaïs Nin and Sylvia Plath to the "sad girls" of Tumblr, Dancyger probes the myriad meanings and iterations of friendship, love, and womanhood. —SMS

See Loss See Also Love by Yukiko Tominaga [F]

In this impassioned debut, we follow Kyoko, freshly widowed and left to raise her son alone. Through four vignettes, Kyoko must decide how to raise her multiracial son, whether to remarry or stay husbandless, and how to deal with life in the face of loss. Weike Wang describes this one as “imbued with a wealth of wisdom, exploring the languages of love and family.” —DF

The Novices of Lerna by Ángel Bonomini, tr. Jordan Landsman [F]

The Novices of Lerna is Landsman's translation debut, and what a way to start out: with a work by an Argentine writer in the tradition of Jorge Luis Borges and Adolfo Bioy Casares whose work has never been translated into English. Judging by the opening of this short story, also translated by Landsman, Bonomini's novel of a mysterious fellowship at a Swiss university populated by doppelgängers of the protagonist is unlikely to disappoint. —JHM

Black Meme by Legacy Russell [NF]

Russell, best known for her hit manifesto Glitch Feminism, maps Black visual culture in her latest. Black Meme traces the history of Black imagery from 1900 to the present, from the photograph of Emmett Till published in JET magazine to the footage of Rodney King's beating at the hands of the LAPD, which Russell calls the first viral video. Per Margo Jefferson, "You will be galvanized by Legacy Russell’s analytic brilliance and visceral eloquence." —SMS

The Eighth Moon by Jennifer Kabat [NF]

Kabat's debut memoir unearths the history of the small Catskills town to which she relocated in 2005. The site of a 19th-century rural populist uprising, and now home to a colorful cast of characters, the Appalachian community becomes a lens through which Kabat explores political, economic, and ecological issues, mining the archives and the work of such writers as Adrienne Rich and Elizabeth Hardwick along the way. —SMS

Stories from the Center of the World ed. Jordan Elgrably [F]

Many in America hold onto broad, centuries-old misunderstandings of Arab and Muslim life and politics that continue to harm, through both policy and rhetoric, a perpetually embattled and endangered region. With luck, these 25 tales by writers of Middle Eastern and North African origin might open hearts and minds alike. —JHM

An Encyclopedia of Gardening for Colored Children by Jamaica Kincaid and Kara Walker [NF]

Two of the most brilliant minds on the planet—writer Jamaica Kincaid and visual artist Kara Walker—have teamed up! On a book! About plants! A dream come true. Details on this slim volume are scant—see for yourself—but I'm counting down the minutes till I can read it all the same. —SMS

Physics of Sorrow by Georgi Gospodinov, tr. Angela Rodel [F]

I'll be honest: I would pick up this book—by the International Booker Prize–winning author of Time Shelter—for the title alone. But also, the book is billed as a deeply personal meditation on both Communist Bulgaria and Greek myth, so—yep, still picking this one up. —JHM

May 14

This Strange Eventful History by Claire Messud [F]

I read an ARC of this enthralling fictionalization of Messud’s family history—people wandering the world during much of the 20th century, moving from Algeria to France to North America— and it is quite the story, with a postscript that will smack you on the side of the head and make you re-think everything you just read. I can't recommend this enough. —CK

Woodworm by Layla Martinez, tr. Sophie Hughes and Annie McDermott [F]

Martinez’s debut novel takes cabin fever to the max in this story of a grandmother, granddaughter, and their haunted house, set against the backdrop of the Spanish Civil War. As the story unfolds, so do the house’s secrets, the two women must learn to collaborate with the malevolent spirits living among them. Mariana Enriquez says that this "tense, chilling novel tells a story of specters, class war, violence, and loneliness, as naturally as if the witches had dictated this lucid, terrible nightmare to Martínez themselves.” —LA

Self Esteem and the End of the World by Luke Healy [NF]

Ah, writers writing about writing. A tale as old as time, and often timeworn to boot. But graphic novelists graphically noveling about graphic novels? (Verbing weirds language.) It still feels fresh to me! Enter Healy's tale of "two decades of tragicomic self-discovery" following a protagonist "two years post publication of his latest book" and "grappling with his identity as the world crumbles." —JHM

All Fours by Miranda July [F]

In excruciating, hilarious detail, All Fours voices the ethically dubious thoughts and deeds of an unnamed 45-year-old artist who’s worried about aging and her capacity for desire. After setting off on a two-week round-trip drive from Los Angeles to New York City, the narrator impulsively checks into a motel 30 miles from her home and only pretends to be traveling. Her flagrant lies, unapologetic indolence, and semi-consummated seduction of a rent-a-car employee set the stage for a liberatory inquisition of heteronorms and queerness. July taps into the perimenopause zeitgeist that animates Jen Beagin’s Big Swiss and Melissa Broder’s Death Valley. —NodB

Love Junkie by Robert Plunket [F]

When a picture-perfect suburban housewife's life is turned upside down, a chance brush with New York City's gay scene launches her into gainful, albeit unconventional, employment. Set at the dawn of the AIDs epidemic, Mimi Smithers, described as a "modern-day Madame Bovary," goes from planning parties in Westchester to selling used underwear with a Manhattan porn star. As beloved as it is controversial, Plunket's 1992 cult novel will get a much-deserved second life thanks to this reissue by New Directions. (Maybe this will finally galvanize Madonna, who once optioned the film rights, to finally make that movie.) —DF

Tomorrowing by Terry Bisson [F]

The newest volume in Duke University’s Practices series collects for the first time the late Terry Bisson’s Locus column "This Month in History," which ran for two decades. In it, the iconic "They’re Made Out of Meat" author weaves an alt-history of a world almost parallel to ours, featuring AI presidents, moon mountain hikes, a 196-year-old Walt Disney’s resurrection, and a space pooch on Mars. This one promises to be a pure spectacle of speculative fiction. —DF

Chop Fry Watch Learn by Michelle T. King [NF]

A large portion of the American populace still confuses Chinese American food with Chinese food. What a delight, then, to discover this culinary history of the worldwide dissemination of that great cuisine—which moonlights as a biography of Chinese cookbook and TV cooking program pioneer Fu Pei-mei. —JHM

On the Couch ed. Andrew Blauner [NF]

André Aciman, Susie Boyt, Siri Hustvedt, Rivka Galchen, and Colm Tóibín are among the 25 literary luminaries to contribute essays on Freud and his complicated legacy to this lively volume, edited by writer, editor, and literary agent Blauner. Taking tacts both personal and psychoanalytical, these essays paint a fresh, full picture of Freud's life, work, and indelible cultural impact. —SMS

Another Word for Love by Carvell Wallace [NF]

Wallace is one of the best journalists (and tweeters) working today, so I'm really looking forward to his debut memoir, which chronicles growing up Black and queer in America, and navigating the world through adulthood. One of the best writers working today, Kiese Laymon, calls Another Word for Love as “One of the most soulfully crafted memoirs I’ve ever read. I couldn’t figure out how Carvell Wallace blurred time, region, care, and sexuality into something so different from anything I’ve read before." —SMS

The Devil's Best Trick by Randall Sullivan [NF]

A cultural history interspersed with memoir and reportage, Sullivan's latest explores our ever-changing understandings of evil and the devil, from Egyptian gods and the Book of Job to the Salem witch trials and Black Mass ceremonies. Mining the work of everyone from Zoraster, Plato, and John Milton to Edgar Allen Poe, Aleister Crowley, and Charles Baudelaire, this sweeping book chronicles evil and the devil in their many forms. --SMS

The Book Against Death by Elias Canetti, tr. Peter Filkins [NF]

In this newly-translated collection, Nobel laureate Canetti, who once called himself death's "mortal enemy," muses on all that death inevitably touches—from the smallest ant to the Greek gods—and condemns death as a byproduct of war and despots' willingness to use death as a pathway to power. By means of this book's very publication, Canetti somewhat succeeds in staving off death himself, ensuring that his words live on forever. —DF

Rise of a Killah by Ghostface Killah [NF]

"Why is the sky blue? Why is water wet? Why did Judas rat to the Romans while Jesus slept?" Ghostface Killah has always asked the big questions. Here's another one: Who needs to read a blurb on a literary site to convince them to read Ghost's memoir? —JHM

May 21

Exhibit by R.O. Kwon [F]

It's been six years since Kwon's debut, The Incendiaries, hit shelves, and based on that book's flinty prose alone, her latest would be worth a read. But it's also a tale of awakening—of its protagonist's latent queerness, and of the "unquiet spirit of an ancestor," that the author herself calls so "shot through with physical longing, queer lust, and kink" that she hopes her parents will never read it. Tantalizing enough for you? —JHM

Cecilia by K-Ming Chang [F]

Chang, the author of Bestiary, Gods of Want, and Organ Meats, returns with this provocative and oft-surreal novella. While the story is about two childhood friends who became estranged after a bizarre sexual encounter but re-connect a decade later, it’s also an exploration of how the human body and its excretions can be both pleasurable and disgusting. —CK

The Great State of West Florida by Kent Wascom [F]

The Great State of West Florida is Wascom's latest gothicomic novel set on Florida's apocalyptic coast. A gritty, ominous book filled with doomed Floridians, the passages fly by with sentences that delight in propulsive excess. In the vein of Thomas McGuane's early novels or Brian De Palma's heyday, this stylized, savory, and witty novel wields pulp with care until it blooms into a new strain of American gothic. —Zachary Issenberg

Cartoons by Kit Schluter [F]

Bursting with Kafkaesque absurdism and a hearty dab of abstraction, Schluter’s Cartoons is an animated vignette of life's minutae. From the ravings of an existential microwave to a pencil that is afraid of paper, Schluter’s episodic outré oozes with animism and uncanniness. A grand addition to City Light’s repertoire, it will serve as a zany reminder of the lengths to which great fiction can stretch. —DF

May 28

Lost Writings by Mina Loy, ed. Karla Kelsey [F]

In the early 20th century, avant-garde author, visual artist, and gallerist Mina Loy (1882–1966) led an astonishing creative life amid European and American modernist circles; she satirized Futurists, participated in Surrealist performance art, and created paintings and assemblages in addition to writing about her experiences in male-dominated fields of artistic practice. Diligent feminist scholars and art historians have long insisted on her cultural significance, yet the first Loy retrospective wasn’t until 2023. Now Karla Kelsey, a poet and essayist, unveils two never-before-published, autobiographical midcentury manuscripts by Loy, The Child and the Parent and Islands in the Air, written from the 1930s to the 1950s. It's never a bad time to be re-rediscovered. —NodB

I'm a Fool to Want You by Camila Sosa Villada, tr. Kit Maude [F]

Villada, whose debut novel Bad Girls, also translated by Maude, captured the travesti experience in Argentina, returns with a short story collection that runs the genre gamut from gritty realism and social satire to science fiction and fantasy. The throughline is Villada's boundless imagination, whether she's conjuring the chaos of the Mexican Inquisition or a trans sex worker befriending a down-and-out Billie Holiday. Angie Cruz calls this "one of my favorite short-story collections of all time." —SMS

The Editor by Sara B. Franklin [NF]

Franklin's tenderly written and meticulously researched biography of Judith Jones—the legendary Knopf editor who worked with such authors as John Updike, Sylvia Plath, Elizabeth Bowen, Anne Tyler, and, perhaps most consequentially, Julia Child—was largely inspired by Franklin's own friendship with Jones in the final years of her life, and draws on a rich trove of interviews and archives. The Editor retrieves Jones from the margins of publishing history and affirms her essential role in shaping the postwar cultural landscape, from fiction to cooking and beyond. —SMS

The Book-Makers by Adam Smyth [NF]

A history of the book told through 18 microbiographies of particularly noteworthy historical personages who made them? If that's not enough to convince you, consider this: the small press is represented here by Nancy Cunard, the punchy and enormously influential founder of Hours Press who romanced both Aldous Huxley and Ezra Pound, knew Hemingway and Joyce and Langston Hughes and William Carlos Williams, and has her own MI5 file. Also, the subject of the binding chapter is named "William Wildgoose." —JHM

June

June 4

The Future Was Color by Patrick Nathan [F]

A gay Hungarian immigrant writing crappy monster movies in the McCarthy-era Hollywood studio system gets swept up by a famous actress and brought to her estate in Malibu to write what he really cares about—and realizes he can never escape his traumatic past. Sunset Boulevard is shaking. —JHM

A Cage Went in Search of a Bird [F]

This collection brings together a who's who of literary writers—10 of them, to be precise— to write Kafka fanfiction, from Joshua Cohen to Yiyun Li. Then it throws in weirdo screenwriting dynamo Charlie Kaufman, for good measure. A boon for Kafkaheads everywhere. —JHM

We Refuse by Kellie Carter Jackson [NF]

Jackson, a historian and professor at Wellesley College, explores the past and present of Black resistance to white supremacy, from work stoppages to armed revolt. Paying special attention to acts of resistance by Black women, Jackson attempts to correct the historical record while plotting a path forward. Jelani Cobb describes this "insurgent history" as "unsparing, erudite, and incisive." —SMS

Holding It Together by Jessica Calarco [NF]

Sociologist Calarco's latest considers how, in lieu of social safety nets, the U.S. has long relied on women's labor, particularly as caregivers, to hold society together. Calarco argues that while other affluent nations cover the costs of care work and direct significant resources toward welfare programs, American women continue to bear the brunt of the unpaid domestic labor that keeps the nation afloat. Anne Helen Petersen calls this "a punch in the gut and a call to action." —SMS

Miss May Does Not Exist by Carrie Courogen [NF]

A biography of Elaine May—what more is there to say? I cannot wait to read this chronicle of May's life, work, and genius by one of my favorite writers and tweeters. Claire Dederer calls this "the biography Elaine May deserves"—which is to say, as brilliant as she was. —SMS

Fire Exit by Morgan Talty [F]

Talty, whose gritty story collection Night of the Living Rez was garlanded with awards, weighs the concept of blood quantum—a measure that federally recognized tribes often use to determine Indigenous membership—in his debut novel. Although Talty is a citizen of the Penobscot Indian Nation, his narrator is on the outside looking in, a working-class white man named Charles who grew up on Maine’s Penobscot Reservation with a Native stepfather and friends. Now Charles, across the river from the reservation and separated from his biological daughter, who lives there, ponders his exclusion in a novel that stokes controversy around the terms of belonging. —NodB

June 11

The Material by Camille Bordas [F]

My high school English teacher, a somewhat dowdy but slyly comical religious brother, had a saying about teaching high school students: "They don't remember the material, but they remember the shtick." Leave it to a well-named novel about stand-up comedy (by the French author of How to Behave in a Crowd) to make you remember both. --SMS

Ask Me Again by Clare Sestanovich [F]

Sestanovich follows up her debut story collection, Objects of Desire, with a novel exploring a complicated friendship over the years. While Eva and Jamie are seemingly opposites—she's a reserved South Brooklynite, while he's a brash Upper Manhattanite—they bond over their innate curiosity. Their paths ultimately diverge when Eva settles into a conventional career as Jamie channels his rebelliousness into politics. Ask Me Again speaks to anyone who has ever wondered whether going against the grain is in itself a matter of privilege. Jenny Offill calls this "a beautifully observed and deeply philosophical novel, which surprises and delights at every turn." —LA

Disordered Attention by Claire Bishop [NF]

Across four essays, art historian and critic Bishop diagnoses how digital technology and the attention economy have changed the way we look at art and performance today, identifying trends across the last three decades. A perfect read for fans of Anna Kornbluh's Immediacy, or the Style of Too Late Capitalism (also from Verso).

War by Louis-Ferdinand Céline, tr. Charlotte Mandell [F]

For years, literary scholars mourned the lost manuscripts of Céline, the acclaimed and reviled French author whose work was stolen from his Paris apartment after he fled to Germany in 1944, fearing punishment for his collaboration with the Nazis. But, with the recent discovery of those fabled manuscripts, War is now seeing the light of day thanks to New Directions (for anglophone readers, at least—the French have enjoyed this one since 2022 courtesy of Gallimard). Adam Gopnik writes of War, "A more intense realization of the horrors of the Great War has never been written." —DF

The Uptown Local by Cory Leadbeater [NF]

In his debut memoir, Leadbeater revisits the decade he spent working as Joan Didion's personal assistant. While he enjoyed the benefits of working with Didion—her friendship and mentorship, the more glamorous appointments on her social calendar—he was also struggling with depression, addiction, and profound loss. Leadbeater chronicles it all in what Chloé Cooper Jones calls "a beautiful catalog of twin yearnings: to be seen and to disappear; to belong everywhere and nowhere; to go forth and to return home, and—above all else—to love and to be loved." —SMS

Out of the Sierra by Victoria Blanco [NF]

Blanco weaves storytelling with old-fashioned investigative journalism to spotlight the endurance of Mexico's Rarámuri people, one of the largest Indigenous tribes in North America, in the face of environmental disasters, poverty, and the attempts to erase their language and culture. This is an important book for our times, dealing with pressing issues such as colonialism, migration, climate change, and the broken justice system. —CK

Any Person Is the Only Self by Elisa Gabbert [NF]

Gabbert is one of my favorite living writers, whether she's deconstructing a poem or tweeting about Seinfeld. Her essays are what I love most, and her newest collection—following 2020's The Unreality of Memory—sees Gabbert in rare form: witty and insightful, clear-eyed and candid. I adored these essays, and I hope (the inevitable success of) this book might augur something an essay-collection renaissance. (Seriously! Publishers! Where are the essay collections!) —SMS

Tehrangeles by Porochista Khakpour [F]

Khakpour's wit has always been keen, and it's hard to imagine a writer better positioned to take the concept of Shahs of Sunset and make it literary. "Like Little Women on an ayahuasca trip," says Kevin Kwan, "Tehrangeles is delightfully twisted and heartfelt." —JHM

Traveling: On the Path of Joni Mitchell by Ann Powers [NF]

The moment I saw this book's title—which comes from the opening (and, as it happens, my favorite) track on Mitchell's 1971 masterpiece Blue—I knew it would be one of my favorite reads of the year. Powers, one of the very best music critics we've got, masterfully guides readers through Mitchell's life and work at a fascinating slant, her approach both sweeping and intimate as she occupies the dual roles of biographer and fan. —SMS

All Desire Is a Desire for Being by René Girard, ed. Cynthia L. Haven [NF]

I'll be honest—the title alone stirs something primal in me. In honor of Girard's centennial, Penguin Classics is releasing a smartly curated collection of his most poignant—and timely—essays, touching on everything from violence to religion to the nature of desire. Comprising essays selected by the scholar and literary critic Cynthia L. Haven, who is also the author of the first-ever biographical study of Girard, Evolution of Desire, this book is "essential reading for Girard devotees and a perfect entrée for newcomers," per Maria Stepanova. —DF

June 18

Craft by Ananda Lima [F]

Can you imagine a situation in which interconnected stories about a writer who sleeps with the devil at a Halloween party and can't shake him over the following decades wouldn't compel? Also, in one of the stories, New York City’s Penn Station is an analogue for hell, which is both funny and accurate. —JHM

Parade by Rachel Cusk [F]

Rachel Cusk has a new novel, her first in three years—the anticipation is self-explanatory. —SMS

Little Rot by Akwaeke Emezi [F]

Multimedia polymath and gender-norm disrupter Emezi, who just dropped an Afropop EP under the name Akwaeke, examines taboo and trauma in their creative work. This literary thriller opens with an upscale sex party and escalating violence, and although pre-pub descriptions leave much to the imagination (promising “the elite underbelly of a Nigerian city” and “a tangled web of sex and lies and corruption”), Emezi can be counted upon for an ambience of dread and a feverish momentum. —NodB

When the Clock Broke by John Ganz [NF]

I was having a conversation with multiple brilliant, thoughtful friends the other day, and none of them remembered the year during which the Battle of Waterloo took place. Which is to say that, as a rule, we should all learn our history better. So it behooves us now to listen to John Ganz when he tells us that all the wackadoodle fascist right-wing nonsense we can't seem to shake from our political system has been kicking around since at least the early 1990s. —JHM

Night Flyer by Tiya Miles [NF]

Miles is one of our greatest living historians and a beautiful writer to boot, as evidenced by her National Book Award–winning book All That She Carried. Her latest is a reckoning with the life and legend of Harriet Tubman, which Miles herself describes as an "impressionistic biography." As in all her work, Miles fleshes out the complexity, humanity, and social and emotional world of her subject. Tubman biographer Catherine Clinton says Miles "continues to captivate readers with her luminous prose, her riveting attention to detail, and her continuing genius to bring the past to life." —SMS

God Bless You, Otis Spunkmeyer by Joseph Earl Thomas [F]

Thomas's debut novel comes just two years after a powerful memoir of growing up Black, gay, nerdy, and in poverty in 1990s Philadelphia. Here, he returns to themes and settings that in that book, Sink, proved devastating, and throws post-service military trauma into the mix. —JHM

June 25

The Garden Against Time by Olivia Laing [NF]

I've been a fan of Laing's since The Lonely City, a formative read for a much-younger me (and I'd suspect for many Millions readers), so I'm looking forward to her latest, an inquiry into paradise refracted through the experience of restoring an 18th-century garden at her home the English countryside. As always, her life becomes a springboard for exploring big, thorny ideas (no pun intended)—in this case, the possibilities of gardens and what it means to make paradise on earth. —SMS

Cue the Sun! by Emily Nussbaum [NF]

Emily Nussbaum is pretty much the reason I started writing. Her 2019 collection of television criticism, I Like to Watch, was something of a Bible for college-aged me (and, in fact, was the first book I ever reviewed), and I've been anxiously awaiting her next book ever since. It's finally arrived, in the form of an utterly devourable cultural history of reality TV. Samantha Irby says, "Only Emily Nussbaum could get me to read, and love, a book about reality TV rather than just watching it," and David Grann remarks, "It’s rare for a book to feel alive, but this one does." —SMS

Woman of Interest by Tracy O'Neill [NF]

O’Neill's first work of nonfiction—an intimate memoir written with the narrative propulsion of a detective novel—finds her on the hunt for her biological mother, who she worries might be dying somewhere in South Korea. As she uncovers the truth about her enigmatic mother with the help of a private investigator, her journey increasingly becomes one of self-discovery. Chloé Cooper Jones writes that Woman of Interest “solidifies her status as one of our greatest living prose stylists.” —LA

Dancing on My Own by Simon Wu [NF]

New Yorkers reading this list may have witnessed Wu's artful curation at the Brooklyn Museum, or the Whitney, or the Museum of Modern Art. It makes one wonder how much he curated the order of these excellent, wide-ranging essays, which meld art criticism, personal narrative, and travel writing—and count Cathy Park Hong and Claudia Rankine as fans. —JHM

[millions_email]

Most Anticipated: The Great First-Half 2021 Book Preview

Folks, we made it to 2021—and, frankly, it looks a lot like last year. We're still dealing with the pandemic, on-going civil unrest, and general malaise, but thankfully there are books. So many books. In fact, at 152 titles, this is the longest, most indulgent Millions preview ever. We could say we're sorry but we all need some joy right now. Our list includes debut novels from Robert Jones, Jr., Gabriela Garcia, and Patricia Lockwood. New novels from literary powerhouses like Viet Thanh Nguyen, Kazuo Ishiguro, and Richard Flanagan. New books by two Millions staffers: Ed Simon and Nick Ripatrazone. And short stories, memoirs, and essay collections too. No matter what you're in the mood for, we think you'll find a book or two to usher in the new year. As usual, we will continue with our monthly previews, beginning in February. Let us know in the comments what we missed, and look out for the second-half Preview in July!

Want to help The Millions keep churning out great books coverage? Then sign up to be a member today.

January

Aftershocks by Nadia Owusu: Owusu’s childhood was marked by a series of departures, as her father, a United Nations official, moved the family from Europe to Africa and back. Her debut memoir is both a personal account of family upheaval and loss—her mother was an inconstant, flickering presence; her father died when Owusu was thirteen—and a meditation on race, identity, and the promise and pitfalls of growing up in multiple cultures; an experience, she writes, that “deepened my ability to hold multiple truths at once, to practice and nurture empathy. But it has also meant that I have no resting place. I have perpetually been a them rather than an us.” (Emily M.)

A Swim in a Pond in the Rain by George Saunders: In his new collection, modern America’s foremost short story writer shares a master class on the Russian short story with the reader. This delightful book of criticism and craft pairs short stories by Chekhov, Turgenev, Tolstoy, and Gogol, with seven essays on how short fiction works and why it remains a vital art form for asking the big questions about life. As Saunders puts it in his introduction, “How are we supposed to be living down here? What were we put here to accomplish? What should we value? What is truth, anyway, and how might we recognize it?” (Adam Price)

The Revolution According to Raymundo Mata by Gina Apostol: The nineteenth-century Filipino writer José Rizal denounced the cruelties of Spanish colonialism, and for that the colonial government put him to death in 1896. Now Filipina-American novelist Gina Apostol explores the father of Filipino literature and the movement for independence which he embodied in her darkly comic new novel. Apostol’s novel is written in the form of a memoir by the titular fictional character, a fellow revolutionary and devoted reader of Rizal. With shades of Roberto Bolaño and Vladimir Nabokov, she writes that her novel was “planned as a puzzle: traps for the reader, dead end jokes, textual games, unexplained sleights of the tongue.” (Ed S.)

The Prophets by Robert Jones, Jr.: Isaiah and Samuel, two enslaved men on a plantation, find solace as each other’s’ beloveds as they resist the brutality which they endure, until their uncomplicated love is challenged by an older enslaved man who arrives and begins to preach the master’s Christianity. Jones excavates the tangled histories of race and gender which mark a profoundly resonant narrative, where the oppressors “stepped on people’s throats with all their might and asked why the people couldn’t breathe.” (Ed S.)

That Old Country Music by Kevin Barry: Audiences and readers have long thrilled to the lilt of a brogue, the so-called gift of the gab, and an often constructed illusion of Irishness. For the real thing, readers can turn to the eleven short stories that make up Irish writer Kevin Barry’s new collection. Eschewing both unearned romance and maudlin sentimentality, Barry roots his collection in the barren soil of western Ireland, where the “winter bleeds us out here,” where people are defined by “the clay of the place.” (Ed S.)

Outlawed by Anna North: A feminist western set in an alternative nineteenth-century America, Outlawed has been billed as True Grit meets The Crucible. Sign me up! The novel’s heroine is 17-year-old Ada, newly married and an apprentice to her midwife mother. After a year passes without a pregnancy, she gets involved with the Hole in the Wall Gang, and Kid, its charismatic leader. North, who is also a senior reporter at Vox, has received praise from Esmé Weijun Wang, who calls Outlawed a “grand, unforgettable tale,” and from Alexis Coe, who writes, “Fans of Margaret Atwood and Cormac McCarthy finally get the Western they deserve.” (Edan)

A Lie Someone Told You About Yourself by Peter Ho Davies: The endorsements for Peter Ho Davies’ latest novel—his fifth work of fiction, and his follow-up to The Fortunes—are pretty dazzling. Sigrid Nunez calls it “achingly honest, searingly comic," and Elizabeth McCracken writes: “Peter Ho Davies has written a brilliant book about modern marriage and parenthood.” From what I can gather, the novel is about a couple’s decision to terminate a pregnancy and their experience with parenthood after that decision. In its starred review, Kirkus writes that this short, spare novel is “perfectly observed and tremendously moving. This will strike a resonant chord with parents everywhere.” (Edan)

Hades, Argentina by Daniel Lodel: In 1978, Daniel Loedel’s half-sister was disappeared by the military dictatorship in Argentina. His first novel, Hades, Argentina, was inspired by this unspeakable event. In the novel, a young student is drawn into Argentina’s deadly politics; years later, having established himself in New York City, he’s pulled back to Buenos Aires and forced to confront literal and figurative ghosts of his past. Publishers Weekly is calling it “a revelatory new chapter to South American Cold War literature.” (Emily M.)

Detransition, Baby by Torrey Peters: “I love trans women,” Torrey Peters once told an interviewer, “but they drive me fucking crazy. Trans women are fucked up and flawed, and I’m very interested in the ways in which trans women are fucked up and flawed.” In Torrey’s debut novel, a trio of New Yorkers—Reese, a trans woman; Ames, a man who used to live as a woman but decided to return to living as a man, and in so doing broke Reese’s heart; Katrina, Ames’s lover and boss—grapple with the decision of how and whether to raise a baby together. (Emily M.)

The Rib King by Ladee Hubbard: Beginning in 1914, Hubbard’s latest (following The Talented Ribkins) tells the story of August Sitwell, a Black groundskeeper who works for a wealthy white Southern family. After taking an interest in three apprentices of the house cook, Miss Mamie Price, Sitwell learns that the family’s patriarch, Mr. Barclay, intends to use his likeness to sell Miss Price’s coveted meat sauce. As time goes on and Sitwell sees none of the profits from Barclay’s sales, he grows resentful of his employer, leading to a shocking retaliation. (Thom)

In the Land of the Cyclops by Karl Ove Knausgaard (translated by Martin Aitken): Knausgaard has set aside making toast and hunting for a lost set of keys for the moment to present us with startling proof that art and the everyday are of the same lineage. Essays on “art, literature, culture, and philosophy” including probing takes on Ingmar Bergman and the Northern Lights, and color reproductions of some worthy contemporary art. (Il’ja)

Pedro's Theory by Marcos Gonsalez: Scholar and essayist (read this piece, or this one) Gonsalez now publishes a work of memoir and cultural analysis that explores the lives of the many "Pedros" of America (taken from the character of the same name from the movie Napoleon Dynamite) as well as his own life as the child of immigrants, asking "what of the little queer and fat and feminine and neurodivergent child of color"? " In a starred review, Kirkus calls this “a searching memoir . . . A subtle, expertly written repudiation of the American dream in favor of something more inclusive and more realistic.” (Lydia)

The Divines by Ellie Eaton: In Eaton’s Dark-Academia-meets-serious-questions-of-selfhood debut, St John the Divine, an elite English boarding school for girls, has been closed for fifteen years following a hushed-up scandal. Josephine, a newly married writer with a promising career, hasn’t spoken to her former friends and classmates — former “Divines” — since. But after revisiting the school, Josephine begins to remember more and more about what happened in the weeks before it shuttered — the Divines’ snobbery, her own cruelty, the violent events that brought the school low — and her growing obsession with the past threatens to derail her adult life and self. (Kaulie)

Craft in the Real World: Rethinking Fiction Writing versus Workshopping by Matthew Salesses: The MFA workshop experience is famously awful, to the point where it can crush enthusiasm and derail careers. This new craft book by novelist and teacher Salesses is a critical addition to the pedagogical canon, laying out how the traditional workshop form and many ideas about "craft" have been envisioned largely by and for white male writers. The book includes exercises and advice for revision and editing and guiding teachers through reimagining what it is to teach and encourage writers. (Lydia)

Summerwater by Sarah Moss: Moss’s Ghost Wall was a sinister, boggy tale of overzealous Iron Age reenactors, and Moss’s latest looks to tap into a similar eeriness. Here, the story involves a community of vacationers in a Scottish resort observing one another warily. Mountains, ceaseless rain, and an ominous loch set the scene for elemental violence. “I was thinking of it almost as a relay race—that each time there’s an interaction across households, the narrative baton passes on,” says Moss in an interview about this dark, choral work. (Matt S.)

Inland Sea by Madeleine Watts: In this wonderful first novel, a young woman endures a “splendid conflagration of emergency” in the midst of a boiling Australian summer. Recently graduated, she takes a job as a dispatcher at an emergency call center, jotting down snippets in her notebook as she is “dropped into emergencies and pulled out, hearing only pieces of whatever the story was, up to fifty times an hour.” The novel revolves around catastrophes of various scales, personal and global but also historical: the narrator’s ancestor, John Oxley, was a “feckless imperialist” who sought to locate an inland sea deep within the “drought-ridden ancientness” which British colonizers had “stolen and didn’t understand.” (Matt S.)

Black Buck by Mateo Askaripour: Black Buck begins with an address that lays out the implicit contract between writer and reader: “You’re likely asking yourself why you should trust me. The good thing is that you already bought this book, so you trusted me enough to part with $26. I won’t let you down.” In the satirical novel that follows, which is sprinkled throughout with pithy tips for closing deals, a charismatic Black man, Darren, is recruited to join the sales team of a noxious, mostly white startup in Manhattan. “He reeked of privilege, Rohypnol, and tax breaks,” says Darren of one of his new colleagues. Sold! (Matt S.)

Life Among the Terranauts by Caitlin Horrocks: Caitlin Horrocks's newest short story collection will please those who like sci-fi, surrealism, and the strange. Claire Vaye Watkins writes that “It’s been a very long time since I’ve come across stories as brilliant, bold, odd, and incandescent as these." The language dazzles as it entices readers into unfamiliar worlds. Marie-Helene Bertino praises, “I marvel at the language...which expands, varies, and never slips.” (Zoë)

The Doctors Blackwell by Janice P. Nimura: Nimura’s biography explores the relationship between two sisters, Elizabeth and Emily Blackwell, and their journey into medicine in the nineteenth century. Elizabeth became the first women in America to receive an M.D., and together these determined and forward-thinking sisters founded the first hospital staffed entirely by women. Their story is a must-read for those who practice medicine and for readers interested in making connections between America’s past and present. As Pulitzer Prize winner Megan Marshall argues, “That the Blackwells arrived in the United States during a cholera epidemic and made it their mission to provide medical care to the underserved, while also promoting the twin causes of women’s rights and abolition, brings this narrative hurtling into the twenty-first century, demanding our attention today.” (Zoë)

The Swallowed Man by Edward Carey: Following up on the triumph of his historical novel Little, Edward Carey’s latest novel The Swallowed Man brings a similarly fabulist perspective to the Italian legend of Pinocchio. The author makes clear Pinocchio’s connection to concerns both universal and contemporary, in a story that’s as much about creation and fatherhood as it is about a conscious marionette who wishes that he was a real boy. “I am writing this account, in another man’s book, by candlelight, inside the belly of a fish,” writes that marionette and Carey proves once again how there is a magic in that archetypal familiarity of the perennial fairy tale. (Ed S.)

The Dangers of Smoking in Bed by Mariana Enríquez (translated by Megan McDowell): Mariana Enríquez returns with a collection of stories that have been likened to Shirley Jackson and Jorge Luis Borges. Kirsty Logan states that “each of these stories is a luscious, bewitching nightmare.” There are ghosts, bones, the disappeared who return home, and witches in this literary horror collection of stories that are sure to disturb as well as provoke questions about politics and society. Lauren Groff promises that “after you’ve lived in Mariana Enríquez's marvelous brain for the time it takes to read The Dangers of Smoking in Bed, the known world feels ratcheted a few degrees off-center.” (Zoë)

The Copenhagen Trilogy by Tove Ditlevsen (translated by Tiina Nunnally): A resurgence on par with the stories of Clarice Lispector or Lucia Berlin, these searing books from the 1960s — available individually in paper or as a hardcover omnibus — are milestones in the development of the life writing we’ve come to call (sigh) “autofiction.” Tracing the author’s struggles with drugs, family, men, and writing — not necessarily in that order — they’ve been brought into English by Tiina Nunnally, one of the most gifted translators at work today. (Garth)

Consent by Annabel Lyon: From the author of The Golden Mean, which won the Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize, Consent is about Sara who, after forcing an annulment of what Sara sees as a hasty marriage to a man targeting an inheritance, becomes a caregiver to her intellectually challenged sister, Mattie. After a tragedy, their lives converge with the second set of sisters. Saskia has put her life on hold to be caregiver for her twin, Jenny, who has been severely injured in an accident. The intersection of the stories, says Steven Beattie in the Quill and Quire, “comes as a shock.” (Claire)

The Uncollected Stories of Allan Gurganus by Allan Gurganus: A new collection of previously unpublished work by the author of Oldest Living Confederate Widow Tells All and a writer Ann Patchett called "one of the best writers of our time." (Lydia)

February

The Removed by Brandon Hobson: Watch out for Brandon Hobson's first novel since his National Book Award Finalist, Where the Dead Sit Talking. The novel convenes as a Cherokee family prepares for a bonfire to celebrate the Cherokee National Holiday and, dually, to commemorate the death of fifteen-year-old son Ray-Ray, who was killed by police. Steeped in memory and Cherokee myth, The Removed is "spirited, droll, and as quietly devastating as rain lifting from earth to sky," per Tommy Orange. (Anne)

Whereabouts by Jhumpa Lahiri: The first novel in nearly a decade from the Pulitzer Prize-winning writer, the story is centered on a woman who moves through a year in her life. Veering from exuberance and dread to attachment and estrangement, she passes over bridges, through shops, pools, and bars, as one season moves into the next until one day at the sea her perspective changes forever. The novel was first written in Lahiri’s acquired language, Italian. (She describes writing in Italian like, “falling in love.”) Lahiri then translated the novel into English herself. (Claire)

Fake Accounts by Lauren Oyler: By most accounts, literary critic and Tweeter extraordinaire Lauren Oyler's debut novel Fake Accounts is set to hit high highbrow on the hypemeter for its “savage and shrewd” account of a young millennial's mediation of life via the internet. It begins with her discovery, while snooping, that her boyfriend is a popular conspiracy theorist, and not so long after she flees to Berlin to embark on her own cycles of internet-fueled manipulation. Heidi Julavits calls the novel, "a dopamine experiment of social media realism” a genre that Oyler has pioneered, and careens forward while appropriating and skewering various forms, including fragmented novels and a Greek chorus of ex-boyfriends. (Anne)

This Close to Okay by Leesa Cross-Smith: The newest novel by Cross-Smith (who was recently longlisted for the 2021 Joyce Carol Oates Literary Prize) explores one life-changing weekend in the lives of two strangers. When divorced therapist Tallie Clark sees a man standing on the edge of a bridge, she talks him down—and brings him to her home where they slowly reveal their selves (and secrets) to each other. The Millions’ Lydia Kiesling writes, “This is a heartfelt and moving novel about grief, love, second chances, and the coincidences that change lives.” (Carolyn)

Milk, Blood, Heat by Dantiel W. Moniz: A debut collection that takes a look at the lives of Floridians who find themselves confronted by moments of personal reckoning, among them a woman recovering from a miscarriage, a teenager resisting her family’s church, and two estranged siblings taking a road-trip with their father’s ashes. The publisher describes the stories as, “Wise and subversive, spiritual and seductive.” Lauren Groff calls the collection “a gorgeous debut.” Danielle Evans says the “characters that drive them are like lightning—spectacular, beautiful, and carrying a hint of danger.” (Claire)

No One Is Talking About This by Patricia Lockwood: One of the most exciting writers these days is also one of the most Online, as longtime fans of Patricia Lockwood all agree. In her debut novel, written in a fragmented style as excerpted in the New Yorker, an unnamed narrator comes home to help her younger pregnant sister through complications. Like the internet itself, what follows is as ecstatically humorous as it is heartbreakingly sad. (Nick M.)

100 Boyfriends by Brontez Purnell: American literature has been a bit too polite for the past few decades. Gone are the thrilling and seedy transgressions of a William S. Burroughs or a “J.T. LeRoy.” Brontez Purnell’s 100 Boyfriends rectifies that in its tales about nymphomaniac men looking for transcendence in a fuck. Recalling Samuel Delany’s queer classic Times Square Red, Times Square Blue, the writer, musician, dancer, and director Purnell presents a jaundiced yet often hopeful vision about sex and meaning, asking “What else is a boyfriend for but to share in mutual epiphany?” (Ed S.)

My Year Abroad by Chang-rae Lee: Tiller, the main character, is an ordinary American college student who has little ambitions. But after Pong Lou, an adventurous Chinese American businessman, takes Tiller as his mentee and brings him on a wild trip around Asia. Tiller blossoms into a young talent. From the award-winning author of Native Speaker, My Year Abroad promises to widen our horizons of a range of contemporary issues—cultural stereotypes, globalization, mental health—by introducing us to kaleidoscopic, surprising, and transformative life experiences. (Jianan Qian)

Milk Fed by Melissa Broder: I’ll never forget the steamy and emotionally complex sex scenes in Broder’s first novel, The Pisces—and not only because they co-starred a dreamy merman. Broder’s latest novel, about a calorie-counting twenty-something who cuts communication from her diet-obsessed mother for ninety days, only to become obsessed with a large-breasted Orthodox Jewish woman who peddles frozen yogurt, sounds wonderful and wonderfully weird. Carmen Maria Machado calls it “luscious” and “heartbreaking,” and Samantha Irby says it’s “deeply hilarious and embarrassingly relatable.” (Edan)

Infinite Country by Patricia Engel: I could praise Infinite Country and recommend it and then praise some more, but others have already done it, and better: R.O. Kwon says Infinite Country “is a wonder, and Patricia Engel is a magician”; Lauren Groff writes that the novel “speaks into the present moment with an oracle's devastating coolness and clarity." The fourth book from prize-winning Colombian-American author Patricia Engel, Infinite Country, is a story of immigration and diaspora that’s both brutal and hopeful, blending Andean myth with the lives of an undocumented family spread across two continents and fighting for reconnection. (Kaulie)

Rabbit Island by Elvira Navarro (translated by Christina MacSweeney): Elvira Navarro’s dark, weird fabulist tales have garnered comparisons to Lynch and Lispector, Walser, and Leonora Carrington alike. Her short stories collected in Rabbit Island—if one can even summarize—take “alien landscapes and turn them into eerily apt mirrors of our most secret realities,” per Maryse Meijer. Perhaps this is why Enrique Villa Matas called Navarro the “true avant-gardist of her generation.” This latest collection gathers psychogeographies of dingy hotel rooms, shape-shifting cities, and graveyards. The overall effect? It’s "like spending a week at an abandoned hotel with rooms inhabited by haunted bunnies and levitating grandmothers," says Sandra Newman. I say, sign me up! (Anne)

The Bad Muslim Discount by Syed M. Masood: In this sparkling debut novel, Anvar Farvis wants out of 1990s Karachi, where gangs of fundamentalist zealots prowl the streets. Meanwhile, more than a thousand miles away in war-torn Baghdad, a girl named Safwa is being suffocated by life with her grief-stricken father. Anvar’s and Safwa’s very different paths converge in San Francisco in 2016, where their very different personalities intertwine in ways that will rock the city’s immigrant community. Gary Shteyngart has called this “one of the bravest and most eye-opening novels of the year, a future classic.” (Bill)

U UP? by Catie Disabato: In Disabato’s sophomore novel, social-media-loving slacker Eve is still mourning her friend Miggy when her best friend Ezra goes missing. Over the course of one weekend bender, Eve searches for clues to Ezra’s disappearance, fends off ghosts, and discovers that everything is not as it seems. Our own Edan Lepucki says, “Disabato’s writing is at once so smooth and sharp that you don’t immediately realize it’s cut you—and deeply.” (Carolyn)

Kink, edited by Garth Greenwell and R.O. Kwon: An anthology of fifteen stories edited by two celebrated authors who promise to “take kink seriously.” The list of contributors includes Alexander Chee, Roxane Gay, Carmen Maria Machado, and Brandon Taylor, and stories are about love, desire, BDSM, and other kinks. “The true power of these stories lies,” says the publisher blurb,” in their beautiful, moving dispatches from across the sexual spectrum of interest and desires.” (Claire)

The Delivery by Peter Mendelsund: Like a millennial Franz Kafka, writer and graphic designer Peter Mendelsund plumbs the absurdities of our society, but rather than focusing on the incipient authoritarianism of crumbling central Europe, he examines the existential despair (and bleak funniness) of the gig economy. The Delivery takes place in an unnamed city where refugees must earn their right to sanctuary as workers delivering food to the ruling class through an app with shades of Uber Eats. Evoking J.M. Coetzee’s Waiting for the Barbarians, if it was about GrubHub rather than colonialism, The Delivery understands that there is no such thing as a free lunch. (Ed S.)

Love is an Ex-Country by Randa Jarrar: For all of this nation’s stated belief in welcoming outsiders, America is often cruel to any demographic that is not white, Christian, straight, and male. As such, when the queer, Arab American Muslim writer Randa Jarrar sets off on a road-trip across the United States in her travelogue Love is an Ex-Country, the resulting narrative is simultaneously a dirge and an encomium. A survivor of both domestic abuse and doxxing, Jarrar’s book is not a simplistic paeon to an imaginary America, but nor does it entirely stop searching for the possibility of some sort of better, hidden country. (Ed S.)

The Kindest Lie by Nancy Johnson: In this debut novel set in Chicago’s South Side and blue-collar Indiana following President Obama’s election, a woman with a settled upper-middle-class existence confronts her difficult past, discovering that the issues of race, class, and identity in America rarely fall along neatly defined parameters; complexity abounds in the makeup of our nation, our families, and ourselves. (Il’ja)

My Brilliant Life by Ae-ran Kim (translated by Chi-Young Kim): Areum, the main character, suffers from an accelerated-aging disorder. Only at sixteen, he looks like an 80-year-old. Even though the family faces his imminent death, they still try to stay positive and live life to its fullest. My Brilliant Life is a breath-taking, heart-felt exploration of the possibility of joy even in the hardest moments of life. (Jianan Qian)

We Run the Tides by Vendela Vida: In pre-tech boom San Francisco, teenagers Eulabee and Maria Fabiola are inseparable. They know every house, every cliff, every tide surrounding their wealthy neighborhood, until there’s a car and a man they don’t recognize. Then Maria Fabiola disappears. Publishers Weekly describes the novel as “channel[ing] the girlish effervescence of Nora Johnson’s The World of Henry Orient while updating Cyra McFadden’s classic satire The Serial;” Kirkus calls it “a novel of youth and not-quite-innocence,” a story of female friendship with all its strengths, betrayals, confusion, and changes. (Kaulie)

Land of Big Numbers by Te-Ping Chen: From the Wall Street Journal reporter whose first-hand observations of contemporary China converge into this stunning debut collection. In the ten stories, we can see how the recent economic boom has impacted and transformed people’s lives in China: the division of values among family members, the unchanging bureaucratic systems, and the request for recognition from marginalized groups. Chen’s fiction is a satisfying literary read as well as precise cultural criticism. (Jianan Qian)

Zorrie by Laird Hunt: Hunt's eighth novel tells the life story of a woman in rural Indiana, from her early days as an orphan who takes a job in a factory to marriage, widowhood, and a hardscrabble farm life. Hernán Diaz raves of the novel, "This is not a just book you are holding in your hands; it is a life. Laird Hunt gives us here the portrait of a woman painted with the finest brush imaginable, while also rendering great historical shifts with bold single strokes. A poignant, unforgettable novel." (Lydia)

Blood Grove by Walter Mosely: The breathtakingly prolific Mosely brings back Easy Rawlins, his most famous literary creation, for a moody mystery set in late-sixties Los Angeles beset by protest and the after-effects of an unpopular war. Rawlins, whose small private detective agency finally has opened its own office, must solve the mystery of a white Vietnam vet who lost his lover and his dog in a violent attack in a citrus grove at the city’s outskirts. But, really, who cares about the plot? It’s Easy Rawlins, so it will be smart, funny, and impossible to put down. (Michael)

Cowboy Graves by Roberto Bolaño (translated by Natasha Wimmer): A trio of novellas by the late Chilean poet and novelist depict socialist upheaval, underground magical realism abroad, and love in the face of fascist violence. (Nick M.)

How the One-Armed Sister Sweeps Her House by Cherie Jones: Trained as an attorney, Jones sets this tale of social class clashes and interconnections in a resort town in her native Barbados. Hailed as “Most Anticipated of 2021” and a “searing debut” by O Magazine; “hard hitting and unflinching” and “unforgettable” say her blurbers Bernardine Evaristo and Naomi Jackson. (Sonya)

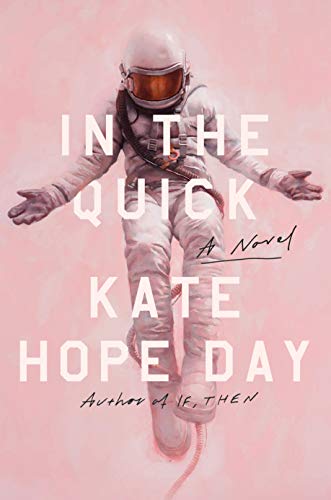

In the Quick by Kate Hope Day: In the latest by the author of If, Then, a young girl named June finds out that her uncle, an aerospace engineer, developed a faulty fuel cell intended for use on a space mission, causing a shuttle to lose power near Saturn and strand the crew indefinitely. Obsessed with finding a way to rescue the far-flung crew, June enrolls in astronaut training, where she performs well enough to earn a placement aboard a space station. Eventually, she fixes the fuel cell, which gives her and her team the ability to stage a rescue mission. (Thom)

Let's Get Back to the Party by Zak Salih: Salih’s debut offers a thoughtful meditation on the evolving landscape of gay male life in America. When gay marriage is legalized in 2015, high school teacher Sebastian Mote finds the occasion unexpectedly bittersweet, since he just broke up with his boyfriend of three years. He pours his energy into nurturing his students, particularly Arthur, a 17-year-old whose openness about his own sexuality is a source of envy for Sebastian. Then he runs into a childhood friend at a wedding—and learns that he’s not alone in his ambivalence towards the new rules of dating. (Thom)

American Delirium by Betina González (translated by Heather Cleary): In her English language debut, award-winning author Betina González interweaves the lives of three characters in a mid-Western city that is unraveling. Deer are attacking people, a squad of retirees trains to hunt them down, and protestors decide to abandon society, including their own children, and live in the woods. Anjali Sachdeva notes, “As González’s characters navigate a world where plants inspire revolution and animals are possessed by homicidal rage, they ask us to consider whether human beings are perhaps the least natural creatures this planet has to offer.” (Zoë)

The Upstairs House by Julia Fine: This high-concept novel involves the ghost of Margaret Wise Brown, the renowned children’s author of the classic bedtime story, Good Night Moon. New mother and Phd student Megan Weiler discovers that the famous author is haunting her house, waiting, apparently, for her estranged lover, the actress Michael Strange. As Megan becomes more drawn into ghostly interpersonal drama, she feels herself losing her grip on reality. Meanwhile, there’s a dissertation to finish and a newborn to care for. Publishers Weekly calls this sophomore effort “a white-knuckle description of the essential scariness of new motherhood.” (Hannah)

We Do This ‘Til We Free Us by Mariame Kaba: In this compilation of essays and interviews, Mariame Kaba reflects on abolition and struggle and explores justice, freedom, and hope. Eve Ewing notes, “This is a classic in the vein of Sister Outsider, a book that will spark countless radical imaginations.” Inspirational and practical, We Do This ‘Til We Free Us offers insights on grassroots movements and collective strategies, and examines the prison industrial complex. Alisa Bierria writes, “This remarkable collection is a powerful map for anyone who longs for a future built on safety, community, and joy, and an intellectual home for those who are creating new pathways to get us there.” (Zoë)

March

Klara and the Sun by Kazuo Ishiguro: The citation for the 2017 Novel Prize in Literature says Ishiguro has “uncovered the abyss beneath our illusory sense of connection with the world." This new novel, his first published since the win, follows Klara, who is an Artificial Friend. While she’s an older model, she also has exceptional observational qualities. The storyline, according to the publisher, asks a fundamental question, “What does it mean to love?” The result sounds like the perfect blend of Ishiguro’s much loved books, Never Let Me Go and the Booker Prize-winning The Remains of the Day. (Claire)

The Committed by Viet Thanh Nguyen: The much anticipated sequel to The Sympathizer, which won the Pulitzer Prize in Fiction, entertains as much as it offers cultural analysis. Set in 1980s Paris, the main character of The Sympathizer sells drugs, attends dinner parties with left-wing intellectuals, and turns his attention towards French culture, considering capitalism and colonization. Paul Beatty says, “Think of The Committed as the declaration of the 20th ½ Arrondissement. A squatter’s paradise for those with one foot in the grave and the other shoved halfway up Western civilization’s ass.” Sharply and humorously written, Ocean Vuong notes that the sequel asks: “How do we live in the wake of seismic loss and betrayal? And, perhaps even more critically, How do we laugh?” (Zoë)

Red Island House by Andrea Lee: It’s been almost fifteen years since Andrea Lee published a book (Lost Hearts in Italy) and I’ve been sitting here waiting for it. Her fiction and memoirs often center on Black characters living abroad, and she writes with such lush and observant precision that you feel you are traveling with her. Her newest novel is set in a small village in Madagascar, where Shay, a Black professor of literature, and her wealthy Italian husband Senna, build a lavish vacation home. Unfolding over two decades, Lee’s new novel explores themes of race, class, and gender, as Shay reluctantly takes on the role of matriarch, learning to manage a household staff and estate. Kirkus calls it “a highly critical vision of how the one percent live in neocolonial paradise.” (Hannah)

The Fourth Child by Jessica Winter: Winter follows her well-received debut (2016’s Break in Case of Emergency) with a multi-generational story of love, family, obligation, and guilt. The novel follows Jane from a miserable 1970s adolescence to an unexpected high school pregnancy and marriage, through the sweetness of early parenthood to the fraught complications of ideology, adoption, and life with a teenaged daughter. (Emily M.)