Diane Williams’ latest collection of stories, Vicky Swanky Is a Beauty, is a slender volume, whose small width, girth, and abundant white space would lure even the most timid reader. Weary of long-term commitments? By all appearances, Williams’s book beckons and says enter. Come sit with stories that begin halfway down the page and run over to the next, and seldom stretch beyond that. The author greets the reader before the stories begin, not with a quote to demonstrate erudition, but rather with a signal that all’s clear: “Perfectly safe; go ahead.”

Diane Williams’ latest collection of stories, Vicky Swanky Is a Beauty, is a slender volume, whose small width, girth, and abundant white space would lure even the most timid reader. Weary of long-term commitments? By all appearances, Williams’s book beckons and says enter. Come sit with stories that begin halfway down the page and run over to the next, and seldom stretch beyond that. The author greets the reader before the stories begin, not with a quote to demonstrate erudition, but rather with a signal that all’s clear: “Perfectly safe; go ahead.”

This is the first hint that something is off kilter. If you abide by the tropes of American horror film, this is the cue to shut the cover and run for the hills. But, of course, from a reader’s perspective, the implication that things may get hairy only heightens the intrigue. Williams’ book, like her stories, aren’t obvious. Had she written, “Danger ahead!” her point would be overstated. Instead we’re given the hint that we’re entering territory where the ground might unexpectedly shift, where anything might occur.

Williams’ stories are sly little creatures who thrive in domestic settings; they are fixated on food, fucks, illness, and death, and the peculiarities of social interaction. The characters who inhabit these stories often appear curiously, media res. Introductions include a woman admitting she’s fallen in love with her neighbor, a mother accusing her daughter of thinking herself a do-gooder, a crestfallen man searching for a better belt buckle, a woman seeking the services of a man with a habit of sharpening knives. And while these acts sound fairly insignificant when rattled off like this in a list, in Williams’ stories the significance of each action is anchored and amplified. That neighbor? Neither woman can get his penis to do anything. “Do-gooder” becomes a slur in the mother’s mouth. The man who sharpens knives? Despite his humility (about the superior state of his lawn), and his kindness (leaving Band-aids with the knives he services), he dies. With these contortions, Williams reveals the essential strangeness in the the everyday.

Getting one’s nails done or running into a recently divorced acquaintance at the grocery store provide windows that open to a larger world of human desire, disappointment, and misunderstanding. The recent divorcee is recognized with delay — “They had been the Crossticks!” — the narrator suddenly realizes, as if she’d know him in an instant, if he were with his wife. The encounters are estranged from their everyday backdrops, and this perspective sears through habituation. It’s a wake-up call to the way we accrue so many details that blunt our recognition of the peculiarities of existence. In life we often hit cruise control to make sure we arrive at to our next destination. This might make us more functional human beings, but it also dulls our perception.

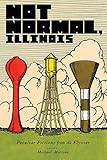

We can’t escape eccentricity, but we can become habituated to it, which is one of Michael Martone’s points in his introductory essay to Not Normal, Illinois, a collection edited by Martone that features stories written by native midwesterners, including Rikki Ducornet, Laird Hunt, Ander Monson, Deb Olin Unferth, Steve Tomasula, and Diane Williams. How bizarre that the state of Illinois, and specifically a city named Normal, home to Illinois State University, has been such a hotbed of experimental and avant-garde fiction. Both The Dalkey Archive and FC2 presses have at some point called Normal home. David Foster Wallace taught at Illinois State, and former FC2 managing director Curtis White still does. Is this merely happenstance? Martone says no, and pinpoints this prolific outpouring as a distinctly regional reaction to the “normalcy” of midwestern culture. He states, “The midwesterners have been normal for so long that it seems normal that they are this way, and the details of normalcy, the construction of what is normal, becomes so, well, normal as to be a cunning transparent disguise. These stories are designed, then, to defamiliarize us to us. By design, they are made to make you see, really see, the things you take for granted all the time for the very first time again.”

We can’t escape eccentricity, but we can become habituated to it, which is one of Michael Martone’s points in his introductory essay to Not Normal, Illinois, a collection edited by Martone that features stories written by native midwesterners, including Rikki Ducornet, Laird Hunt, Ander Monson, Deb Olin Unferth, Steve Tomasula, and Diane Williams. How bizarre that the state of Illinois, and specifically a city named Normal, home to Illinois State University, has been such a hotbed of experimental and avant-garde fiction. Both The Dalkey Archive and FC2 presses have at some point called Normal home. David Foster Wallace taught at Illinois State, and former FC2 managing director Curtis White still does. Is this merely happenstance? Martone says no, and pinpoints this prolific outpouring as a distinctly regional reaction to the “normalcy” of midwestern culture. He states, “The midwesterners have been normal for so long that it seems normal that they are this way, and the details of normalcy, the construction of what is normal, becomes so, well, normal as to be a cunning transparent disguise. These stories are designed, then, to defamiliarize us to us. By design, they are made to make you see, really see, the things you take for granted all the time for the very first time again.”

Diane Williams is definitely an author who, as a good Russian Formalist might say, defamiliarizes. Her stories are distorted mirrors of domesticity, not because they skew the world but because they provide a magnified lens through which we can see what’s always been present but generally escapes notice. This happens quite literally, in the story “This Has to Be the Best.” The narrator goes to a sex shop, greets a familiar saleswoman, but the saleswoman exclaims, “I have never seen you before in my life!” The narrator dismisses this lack of recognition as a result of poor lighting. Does she truly not look herself? Does the saleswoman suffer from prosopagnosia? Is there some ulterior motive? We’re left to wonder. And yet, we’ve all been on one side of this kind of interaction, either failing to remember a face, or encountering an acquaintance who has no recollection of meeting us before.

Williams is also masterful at orchestrating exquisite contrasts, such as in the story “Glee.” If one forgets for a moment the popular television show, the title conjures good feeling, and begins: “We have a drink of coffee and a Danish and it has this, what we call — grandmother cough-up — a bright yellow filling. The project is to resurrect glee. This is the explicit reason I get on a bus and go to an area where I do this and have a black coffee.” It’s not joy, but glee that the narrator has lost and seeks to recapture, by way of coffee and a danish with custard like cough-up and conversation with this friend. Williams strings words in a way that thrills the ear. The syntactic play within the sentences shouldn’t be underestimated in providing their own form of readerly delight. Here the sentence riffs on the repetition of the hard “e” combined with the resonance of coffee and cough-up. And yet disgust is served alongside this happiness, a joyful meeting over grandmother’s cough-up?

Such specificity brings forth abstracted feelings. When the narrator in “Glee” later turns on the television, and watches a show where a suitor proposes marriage and is turned down, the narrator thinks, “when something momentous occurs, I am glad to say there is a sense of crisis.” The sense of catharsis received from watching someone else’s staged tragedy heightens a sense that something of significance is occurring even if this isn’t the case, and Williams captures this sentiment oh so succinctly. As readers we are twice removed, making this a meta-commentary on the role that stories play in our own lives.

Throughout Vicky Swanky Is a Beauty, there’s a pervasive fear of disappearance and self-ablation; a character fears being forgotten, a daughter and husband disappear, and yet another character cancels her own appearance. We exit, however, with an awareness of Williams’ authorial wand waving over the dark linguistic matter as she acts as the conduit through which these words and images appear: “The star! The cross! The Square! A single sign shows the tendency. Can people avoid disaster? Yes. I leave my readers to draw their own conclusions.” Williams’ endings often leave the reader with more questions than conclusions, and yet it’s this openness that allows her stories to inhabit dimensions of experience far vaster than their petite packaging would suggest. Even without the cameo appearances by the character “Diane Williams,” it’s unlikely that anyone who’s attempted to tease apart a handful of Williams’ stories will forget her linguistic precision, the ways she whittles sentences into solid gems, or her wonderfully strange way of seeing.