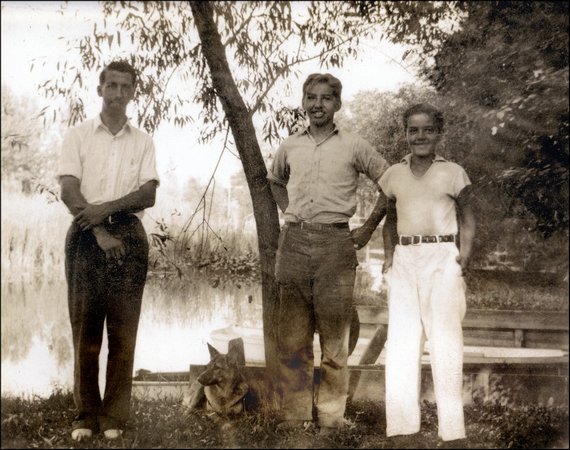

(Photo courtesy the author. The author’s father is in the center, flanked by his brothers.)

My father is a quiet man. He is eighty-eight and, characteristic of his generation, stoic. He comes from German stock and I think he was indoctrinated with the nineteenth-century Teutonic notion that discourse upsets the digestive system. He has never had, to my knowledge, a digestive problem, so presumably the practice has served him well. It came as a great surprise, consequently, to learn that he was writing his memoirs.

I was returning home to Maine and called my father during a layover at the Detroit airport. I’d been away a week. My father lives alone, only a few steps from my door. He gets lonely when I am out of town. I was expecting his lonely or his bored voice to answer the phone. He picked up. “I’ve got a little project going on,” he said, sounding full of joy, and perhaps even excitement. “I’ve got a manuscript I’m working on.” My father finished high school–barely–went to war, returned from war, went to work at International Harvester in Indiana, retired, and eventually moved close to me after my mother, his wife of fifty-three years, died suddenly three years ago. He is not a writer, though his camp letters to me many years ago betrayed an ability to fashion the written word in a surprisingly vigorous manner, particularly when stacked up against the troubled verb conjugations of his spoken words. “What do you mean, Dad, a manuscript?” I asked.

“I’m writing the story of my childhood, of three brothers growing up in Ft. Wayne during the depression.”

“That’s fantastic.”

“My days just fly by,” he continued. “I sit down at the computer and start writing and before you know it, the day is gone. I even forget to eat sometimes!” He laughed at himself over this.

A few years ago I began feeding dad books I thought he might enjoy. There was no reason to think he would take my advice and read them. I have no childhood memory of seeing him with a book. He had magazines and would flip through those, and he’d skim the newspaper, but no books. On a hunch, I loaned him Paul Theroux’s book about exploring the islands of the south Pacific, The Happy Isles of Oceania. He devoured the book and asked for more. I gave him another Theroux. Again, he tore through it, as he did most of the books I pushed his way, chiefly adventure and travel books. My mother used to say, “Your father is a dreamer.” She laughed at this, but was in essence complaining. He had, over the years, dreamed of homesteading in Alaska, sailing around the world, exploring remote and lost islands, as well as many lesser adventures. To her point, he never seemed settled, was always a pulsing nerve shy of rest. I wondered if books had suddenly allowed him to exercise his dreams; if, like a pacing dog, he could now just stop, book in lap, relax. I stocked a tailor-made library for a man who had suddenly discovered the world of the book.

A few years ago I began feeding dad books I thought he might enjoy. There was no reason to think he would take my advice and read them. I have no childhood memory of seeing him with a book. He had magazines and would flip through those, and he’d skim the newspaper, but no books. On a hunch, I loaned him Paul Theroux’s book about exploring the islands of the south Pacific, The Happy Isles of Oceania. He devoured the book and asked for more. I gave him another Theroux. Again, he tore through it, as he did most of the books I pushed his way, chiefly adventure and travel books. My mother used to say, “Your father is a dreamer.” She laughed at this, but was in essence complaining. He had, over the years, dreamed of homesteading in Alaska, sailing around the world, exploring remote and lost islands, as well as many lesser adventures. To her point, he never seemed settled, was always a pulsing nerve shy of rest. I wondered if books had suddenly allowed him to exercise his dreams; if, like a pacing dog, he could now just stop, book in lap, relax. I stocked a tailor-made library for a man who had suddenly discovered the world of the book.

But somewhere along the line, the enthusiasm for books left him. It took a couple of years, but when it happened it happened with the same abruptness with which it began. It was as if a switch, suddenly turned on, had just as suddenly been flipped off. I kept bringing him books, but he had lost what he’d so startlingly discovered. To this day, now a half dozen years later, he laments the loss. “I just can’t concentrate,” he recently confessed.

“So, dad. Am I going to get to read this manuscript of yours?” I asked from the airport.

“Oh, yes. I want you to,” he said. “But I need an editor. Can you help me?”

I assured him I would help and that I looked forward to reading his memoir.

“My what? Memoir?”

“Yes,” I said. “Memoir. It’s a way of telling your life story. I think that’s what you’re working on.”

“They make memoirs into books?”

“Yes, in fact, it’s a very popular genre right now.” I winced at the word genre.

“I want to write like Mark Twain,” he said. “I want to use normal words like normal people, people like me, use.”

I told him I understood, but mentioned that Twain had an impressive command of the language. This gave him pause. “Regardless, Dad, just write the story the way it sounds best to you,” I said. “If you do that, you’ll be fine.”

I stopped in to see him as soon as I got home. He was bent over his computer keyboard, hunting and pecking, papers on the floor, a cold cup of coffee on the kitchen table. He looked up and acknowledged me. He didn’t ask about my trip. He didn’t ask how I was. He asked me to read something and handed me a page. (Subtlety is an attribute my father never managed to develop.) “The Great Depression had its grip on us,” it began. The story continued:

Life became a struggle for everyone. There were few jobs to be had, if any. Dad spent many days looking for work of any kind and would come home discouraged only to start out the next day and try again. He got lucky one day and landed a job hauling coal to homes and unloading it. He would save his last load for our house. Mom would have a hot supper ready for him and he would eat while still covered with coal dust. Mom would unload the coal, shoveling it down a shoot into the basement. We would watch through the frosted window. I felt sorry for her but we couldn’t help. We were too small.

“It’s a wonderful image, Dad,” I said. “Your father covered in coal dust, eating, while grandma shovels coal into the basement. The brothers watching through a frosted window. Very nice.” He smiled and handed me another page.

Looking back at the thirties, in perspective, people would say that we were poor and maybe we were, but we didn’t know it. We had a lot of company and thought it was the norm. I wore Ralph’s clothes and when I got done with them they went to Ken, if still wearable. We were great fixers, even glued rubber soles on our shoes to extend their use. Even so, it was a simple life. In those days there was no refrigeration. In the summer the ice man would come in a horse-drawn wagon with a canvas over a big block of ice. He would chip off a piece for our ice box and with tongs carry it into the house. While he was gone we would gather up the loose chips and suck them. In the winter we had a box on the window sill and kept our food there simply raising the window to reach it.

And so the stories flowed: The brothers running catfish lines on Lake James at night. A beloved family dog poisoned. A rifle accidentally discharged. A near drowning. Motorcycle accidents. I was not familiar with many of them, my father being, as I stated, of that silent generation. Suddenly he was an open gushing spigot. Then, just like the reading, and without warning, the spigot clamped shut.

“This writing business is hard work,” dad complained one afternoon as I was visiting him. I acknowledged that it is, indeed, hard work. “I don’t know how you do it everyday, write like you do.” I joked that there are more days than not when I wonder the same thing. He had abruptly ended his story as the three brothers, now grown, headed off to war, “tapped on the shoulder by Uncle Sam,” as he put it. “Are you going to tell the story of the war?” I asked. He said no, that he did not want to “open that can of worms.” He stated that he had successfully kept that experience under wraps and intended to continue doing just that. I said that sometimes writing is like drawing from a well and if you rest for a time the well refills. Maybe, I told him, he’d someday want to write more stories. He said he didn’t think so. He has more stories, he admitted. But, he confessed, he didn’t want to carry on. And that was that.

There is one line in his memoir I find particularly poignant. It is a clunky line that I wanted to fix but resisted. My father and his brother Ken had recently been talking, recollecting stories for the memoir. My father writes, “Just the other day Ken said, ‘When one of us is gone who will there be to talk to, that not having been there will understand?’” To which my father simply replies, “How true.” It is, in some fashion, the question every writer asks. How true.