Like most writers who meet young, Debra Jo Immergut and I have been talking about writing our whole lives. From Iowa City’s workshops and bars to NYC, where we struggled to raise kids and pay rent, to opposite sides of Massachusetts, where we live now with our respective families, we’ve been wondering aloud together what sustains our motivation to write when there is always so much else to do.

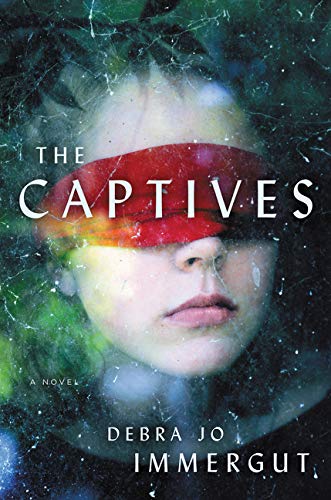

The exciting occasion for this latest conversation is Immergut’s debut novel, The Captives, on June 5—26 years after selling a short-story collection not long after Iowa. The Captives is part of a two-book deal at Ecco/HarperCollins and will be published in a dozen countries over the next year. Publisher’s Weekly praises this literary novel as “ingenious” and “nail-biting,” and Booklist calls it a “stunning debut.”

1. The Long Game

The Millions: You published a collection of short fiction, Private Property, in 1992, just after Iowa, and now you have your debut novel coming out. That’s a pretty unusual publishing trajectory. How does it feel to debut again? What stopped, or stalled, in the past, and what inspired you to return to your work?

The Millions: You published a collection of short fiction, Private Property, in 1992, just after Iowa, and now you have your debut novel coming out. That’s a pretty unusual publishing trajectory. How does it feel to debut again? What stopped, or stalled, in the past, and what inspired you to return to your work?

Debra Jo Immergut: First, it’s clear to me now that I was woefully unprepared the first time around. In New York right out of college, I enrolled in a nighttime creative writing class at Columbia U, mostly because I hated being a bored entry-level office worker. In quick succession after that, I applied and was accepted to Iowa, then sold that story collection, basically with the only six or seven stories I’d ever written. That was freaky and wonderful. But I also found the publishing experience, being reviewed, giving readings, dealing with world-weary agents and editors, all that, vertigo-inducing. Publishing the tender stories of one’s youth, putting them out there for everyone to ogle, can make a girl feel a bit vulnerable! This came as a surprise to me. That’s how green I was.

Then I wrote a novel that didn’t sell. At the same time, I became a parent and needed to earn money, so I decided to find myself a full-time job again. I kept writing—on my own, in writing groups—but had little urge to pursue publishing in any dedicated way until I was laid off in 2015. I knew I was ready and to my great joy, I discovered that all the miles and years behind me, and especially the defeats, seemed to give me new power and a more versatile set of tools. And I just felt tough enough to take whatever reaction the world was going to give me. I sent the manuscript that would become The Captives to an incredible literary agent, Soumeya Bendimerad Roberts, who plucked it out of her digital slush pile. Soumeya offered brilliant feedback and helped me nail the ending, and for that I will be eternally thankful. She quickly sold it in a kind of surreal, dream-come-true scenario, and here I am, debuting again, with much more equanimity and huge gratitude. So, yes, a long trajectory—but how it was meant to be, for me, apparently.

Scott, how about you—do you feel like life has made you a better writer?

TM: Probably, but not in a direct way. I’m not sure my craft skills are any better. I’m maybe more patient. Certainly more vulnerable, which just comes with the territory when you have three kids. But in a larger sense, it’s that vulnerability that re-engaged me in writing. One of the few business books worth reading is called Only the Paranoid Survive. It’s written by the late Andrew Grove, the legendary former CEO of Intel. A Hungarian Jew born in 1936, Grove evaded capture from both Nazis and communists in his life, so he comes by his title honestly. As I went along in my own career, I started to understand what he meant from another perspective—how much of American business runs on fear. It seemed to me that the consequences of this fact—psychological, emotional, social—weren’t something that could be acknowledged. Fiction became the only way I could tell the truth about work.

TM: Probably, but not in a direct way. I’m not sure my craft skills are any better. I’m maybe more patient. Certainly more vulnerable, which just comes with the territory when you have three kids. But in a larger sense, it’s that vulnerability that re-engaged me in writing. One of the few business books worth reading is called Only the Paranoid Survive. It’s written by the late Andrew Grove, the legendary former CEO of Intel. A Hungarian Jew born in 1936, Grove evaded capture from both Nazis and communists in his life, so he comes by his title honestly. As I went along in my own career, I started to understand what he meant from another perspective—how much of American business runs on fear. It seemed to me that the consequences of this fact—psychological, emotional, social—weren’t something that could be acknowledged. Fiction became the only way I could tell the truth about work.

2. The Iowa Effect

TM: There’s a pretty familiar critique of writing programs—how they have a deadening or homogenizing effect on American writing—that keeps appearing in the press. You can count on one every couple years, like a spring snowstorm in Boston. Laura Miller wrote a broadside for Salon in 2011 that’s still circulating. And there was recently a reprise in The Atlantic. Of course, all institutions have biases, and the Workshop is no exception. But looking back, what’s your take on the Workshop’s overall impact on your development as a writer?

DI: I don’t think I’d be a writer without Iowa, honestly. My main challenge over the years has been believing I was worthy. Being admitted to Iowa made that outlandish dream seem just a bit more within reach. And just occupying a spot at the same table as the writers who taught me—Elizabeth Tallent, T.C. Boyle, James Alan McPherson, Francine Prose, Tom Jenks, Allan Gurganus—that was so legitimizing. And of course, two years to just write. And the community of my peers…like you, and my husband John. Definitely the most important takeaway.

TM: I totally agree. More than anything else, Iowa made it OK to own your ambition. It wasn’t embarrassing to leave some social event to write—which felt excruciatingly pretentious before to me. But how about what you learned? I remember Frank Conroy saying something like, “We can’t teach writing but we can put the writer in the path of inspiration.” Or maybe that was in the marketing material. See, the adman in me has blurred all the boundaries. What about you? Did you “learn” how to write there?

DI: It’s murky, exactly what we got schooled in at Iowa. Life lessons, absolutely—I was 23, and it was a wild mess of possibility there. A lot of what I took away about writing, though, seems due to random luck and chemistry, looking back. I landed in a workshop with Madison Smartt Bell. His work then was all about youth and darkness and brutal honesty—and his model gave me courage to delve into the trickier parts of my own experience. I wasn’t really doing that when I arrived—but by the time I left, I was poking into all kinds of suburban American twistedness.

Iowa and maybe all good MFA programs will help you wrap your mind around sentences, tone, and how to build those things into a compelling short story. They might help you find your voice—or, if you aren’t careful about what you’re soaking up, they might sway your voice toward whatever is the prevailing tone of the moment. Looking back at my short stories in Private Property, I think I did get a bit confused at times. But that’s what being a young writer is about, right? Absorbing influence, trying to locate your voice among many others. All these years later, all that has left just a faint residue. I spend exactly no time thinking about voice.

Now I think more about the reader’s’ experience, and that’s where I’ve had to teach myself all sorts of foundational tactics that were not talked about at Iowa. How to construct the framework of a strong plot, how to slowly delineate a fully realized character over 300 pages or more, how to keep storylines moving and shifting in surprising and believable ways. In The Captives, I tried to illuminate both my characters by tracing the two opposing desires that drive them—the yearning for freedom versus the longing for redemption and moral clarity. Both Frank and Miranda are driven by these desires, but they’re in constant flux. That builds character—but also builds a lot of conflict and tension between them—and that gave me plenty of ideas for building my plot. And it feels true to life, I think…I mean, the underlying drivers of our decisions really do change enormously over time.

TM: Iowa was essential for me too in the way that it demystified the actual career of writing. That being said, I’ve always found the term “workshop” to be a misleading metaphor for a writing program. I understand that it’s linked to the romance of the American craftsperson as a symbol of authenticity: simple, honest, true—especially in opposition to those decadent Europeans. But writing is not making a table. I found the workshop—back then at least—tended to privilege craft over plot. We rarely spoke about character development or scale with a few exceptions. One of my favorite moments in James Alan McPherson’s class was a critique of one of my all-dressed-up-with-no-place-to-go stories. I don’t remember his exact words, and I can’t possibly reproduce his style, but it was something like: “So, if you are writing a story about two ladies having tea and then you mention that a bear has entered the room and started smashing things up, but you keep writing about the two ladies, well…the reader is probably going to be distracted.” What you call the reader’s experience is the taking-care-of-business part of writing that isn’t about lyrical sentences. It’s about sustaining attention.

DI: Definitely. Question for you, Scott: What do you think we gained and lost by not pursuing academic careers, as most of our classmates did?

TM: Funny you mention it. I think it’s a really big question for any writer or aspiring artist. Especially for young people who have passion but lack context. It’s hard to even imagine the trade-offs of a so-called “writer’s life” beyond the cliches. I’m not sure if I lacked confidence in my work or was just too lazy and bourgie. Part of the confessional truth for me is that I really hate applying for grants and awards to support a family. I blame my father. Probably something I should explore in therapy. My work in advertising and strategy has, for all its flaws, given me access to all kinds of crazy people and experiences, and a relatively steady income when I’m not getting fired, which happens more than is ideal. But I do teach a grad class one night a week now in Boston. And I love it. Teaching is my last idealism. Maybe I had to leave the church to keep my religion.

DI: I also feared I’d feel suffocated in the academic hothouse. But with that fork in the road far behind me now, I can honestly say 15 years in corporate magazine publishing—9 to 5 in a cubicle five days a week—was pretty stultifying, too! And my friends who teach have written and published much more, so I do feel like it was a real trade-off and I paid a price, turning away from that. When I was laid off from my job in 2015, I applied for a MacDowell Colony fellowship (yes, it is a form of writing grant—four weeks of freedom to create at no cost, gorgeous and delicious). At dinner the first night there, I talked to the other fellows and realized that my coming straight from a full-time office job made me a freak, an outlier. These people had all been living the artists’ life you describe—grants, residencies, teaching, and whatever else they needed to devote themselves to their art. Of course this made feel paralyzed by imposter syndrome for the entire first week. But then I just decided, fuck it, I’m going to embrace this difference, and think about what it took to find meaning and sometimes even joy in that corporate cubicle. I poured that energy into my work, and it comes out in my Captives characters and even more in my second novel, which is all about how one can be driven to desperate measures trying to balance creative work and paycheck work.

Interestingly, I’m now doing some more stints teaching, and I’m totally enjoying it…so maybe we’re both veering back in that direction after opting out.

3. Genre Bending

TM: The Captives is being called a literary thriller, a psychological thriller, a plot-driven literary novel…What does writing to so-called genre mean for a literary writer? Does the distinction still matter? How did it shift your approach?

DI: It’s been fascinating to watch people variously classify The Captives, because it really does seem to straddle the boundaries. But for me, there is only careful writing and crap writing—and maybe I’d say there is another level that is reserved for astounding writing. Yes, we can call books in which crimes are committed crime novels—as mine is called, sometimes. Books that have thrilling plots can be called thrillers, as mine is called sometimes. I’m OK with that. I try to be a careful writer and create work that is as original and textured as my addled brain will allow. I think a lot of people who are currently tagged as genre authors do that. Look at John le Carré’s characters…those are complicated people. And “literary writers” can be pretty careless. The term “literary” can be used to cover up a multitude of sins against readers. We should cheer for writers who pay painstaking attention to language and character, who are ambitious, challenging, and pushing the form forward. I just don’t know if we should label them.

I enjoy constructing a story with pace and twists, but that’s not what drives me. The big unanswered questions are really what make me sit in the chair. Does that make me a literary writer or a genre writer?

TM: This gets us to maybe the only frame on this question that really matters, which is marketing. I’ve been doing this strategy thing for 20 years now, so I can say with some confidence that classifications matter. There is a famous experiment that the design firm Ideo performed in grocery stores. They designed a shopping cart that they partitioned into separate sections for vegetables, fruits, meats, etc. They found that when they designated bigger areas for vegetables, people bought more vegetables. A lot more. Genre is, obviously, a powerful framing device.

DI: If you play with crossing or mixing genres, you have to bet on confounding some readers’ expectations. But ideally, I win them over with my story’s charms. That’s the goal.

TM: Yes. Beyond the market, the dream is that people read our stories and books on their own terms. And if that’s the goal, if we want to blow people’s minds (in the best way) to create powerful experiences that linger, then we have to risk striking out into new territory, including mixing genres.

DI: Definitely. However my work gets tagged, I’m looking for that brain-gut connection—I want to provoke readers intellectually and viscerally. Revving the pulse, turning a twist in the stomach or the heart, maybe making a bit of sweat pop up. To cause a deep stirring in people one has never even laid eyes on…to me, that’s a writer’s magical power.