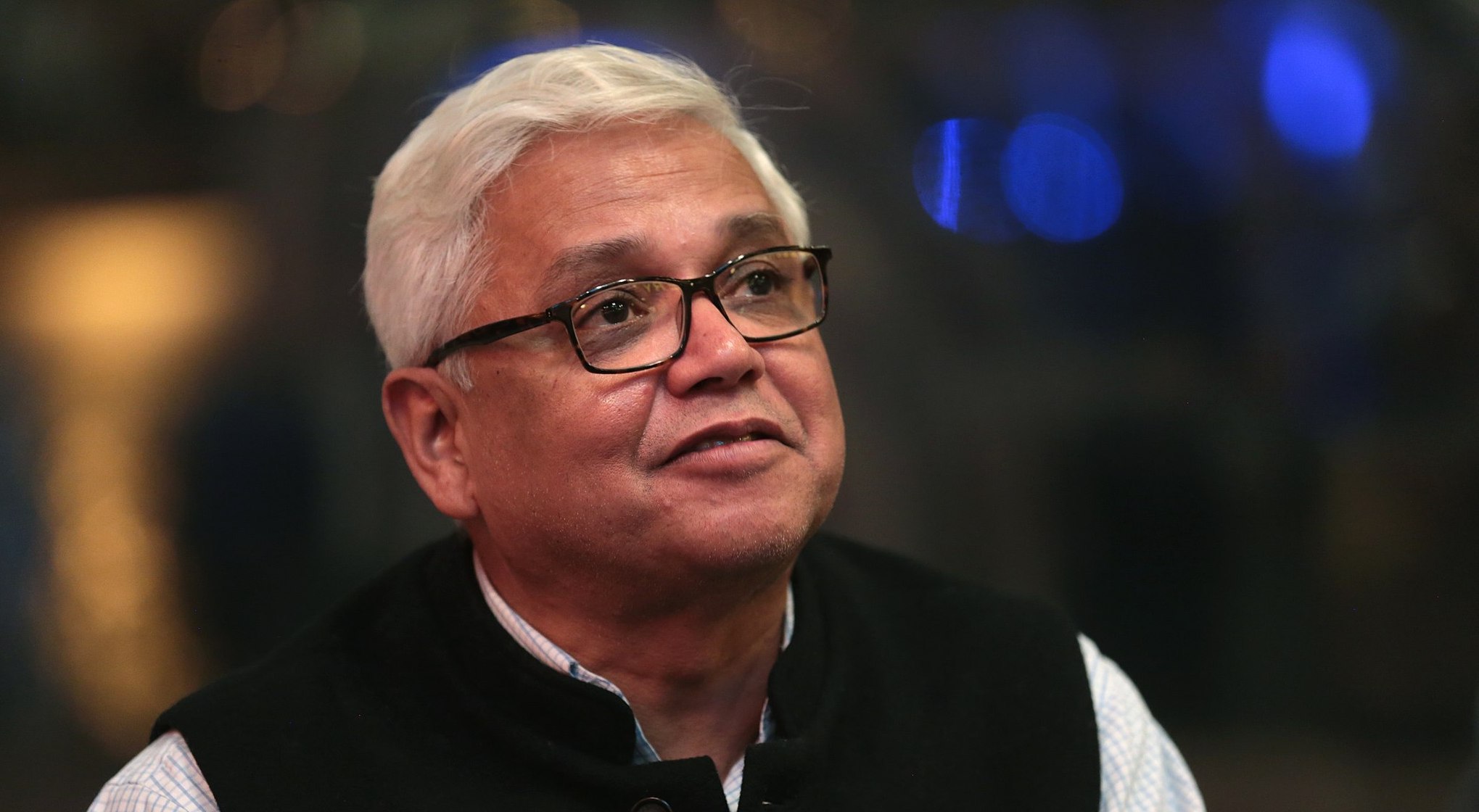

For many in my generation, living and breathing amidst the colonial ruins and ebbing pride of Calcutta, Amitav Ghosh was the first writer in English to write about the everyday life that we lived. The first writer to write of the streets we took, the bookstores we shopped in, the distinguished poverty we lived in, in the language in which we weren’t accustomed to reading of these things.

His life and mine began mere miles apart. But he, with his Booker near-misses, his Oxford doctorate, his immersive prose and me with my lying on a bed and staring at the ceiling fan, have had rather parallel lives.

When I first touched his The Shadow Lines, I did not know who he was. I was 15 years old, it was a summer afternoon and I was rummaging in the one room of the attic of our rented home that held all our stuff. The book had no cover and its first 12 pages were missing. It lay open, underneath things that had been moved from house to house as we moved along with them.

When I first touched his The Shadow Lines, I did not know who he was. I was 15 years old, it was a summer afternoon and I was rummaging in the one room of the attic of our rented home that held all our stuff. The book had no cover and its first 12 pages were missing. It lay open, underneath things that had been moved from house to house as we moved along with them.

It had been hurriedly put down. I imagined an aunt or an uncle reading it and then being called away. I imagined her shoving the book into the last box, assured that she would open it in the new house soon. I imagined the boxes getting comfortable in the rented rooms that grew increasingly smaller, and us losing the need to open those that held non-essential things. In 1945, my young grandparents had walked from what is now Bangladesh to what is now Bengal, as the British prepared to partition India. Since then, till about 2007, our family lived in one rented home after another. In its crowded home in a cardboard box, where it shared space with terra cotta dolls, Bengali translations of The Rig Veda, and the blankets that were meant to cushion blows to the fragile things, The Shadow Lines, with its dog ears and its maddening old smell, was the very Calcutta refugee that it speaks of in its own pages.

It had been hurriedly put down. I imagined an aunt or an uncle reading it and then being called away. I imagined her shoving the book into the last box, assured that she would open it in the new house soon. I imagined the boxes getting comfortable in the rented rooms that grew increasingly smaller, and us losing the need to open those that held non-essential things. In 1945, my young grandparents had walked from what is now Bangladesh to what is now Bengal, as the British prepared to partition India. Since then, till about 2007, our family lived in one rented home after another. In its crowded home in a cardboard box, where it shared space with terra cotta dolls, Bengali translations of The Rig Veda, and the blankets that were meant to cushion blows to the fragile things, The Shadow Lines, with its dog ears and its maddening old smell, was the very Calcutta refugee that it speaks of in its own pages.

I read with the joy of a reader who had so far only read the English literature of the English. Ghosh was not writing the Calcutta of the colonisers, the Calcutta of the north with its lofty crumbling houses belonging to the Queen’s viceroys and their good friends; he was writing the south Calcutta where I lived, the south Calcutta where refugees from Bangladesh—like my grandparents had been and like the narrator’s grandmother had been—landed.

I did not know what a seminal text it had already become in postcolonial literature as I read it, but I remember the first feeling of oneness. Delirious, I wrote to Ghosh through the “Contact” page on his website. “I have been forever changed thanks to your book. My own grandmother is the same woman you have spoken of in Shadow Lines. [And then, in a leap of audacity] I have to ask you if you once had a grandmother who was like this.” Ghosh replied, “Dear Soumashree, thank you for writing to me. I am happy that the book resonated with you.”

The door to the dark underbelly of joy at an author’s acknowledgement had been opened.

As that summer gave way to the next, the newspapers filled with previews of Ghosh’s Sea of Poppies, the first in his Ibis trilogy. By then I had read three more books by Ghosh—The Hungry Tide, The Calcutta Chromosome, and Dancing in Cambodia—and he had become one of the writers whom I would regard as a personal literary trainer.

As that summer gave way to the next, the newspapers filled with previews of Ghosh’s Sea of Poppies, the first in his Ibis trilogy. By then I had read three more books by Ghosh—The Hungry Tide, The Calcutta Chromosome, and Dancing in Cambodia—and he had become one of the writers whom I would regard as a personal literary trainer.

On July 10, 2008, I was browsing a bookstore in a south Calcutta mall when I noticed that Sea of Poppies was to be released on that evening by Ghosh himself. It was mid-afternoon then and the book release was scheduled at 7 p.m. Seven p.m. was also exactly the hour at which my mathematics tutor would arrive at my house. I went home and fell prostrate at my mother’s two feet.

My mother, the staunch disciplinarian, told me that not only was I allowed to cook up a story for my absence at the math class, but that she would come with me to the book release too.

The sun set on the glorious day and my mother and I caught a yellow taxi to go to the mall. On the way, I called my math teacher.

“Miss, I am very sorry, but I will be a little late today.”

“Why, what is the matter?”

“It is my eye, miss, I have had to come to the doctor.”

“What happened to your eye?”

“My left eye has developed a blind patch. I cannot see through the patch, though my vision is okay for the rest of the eye.”

“Oh. Okay. Yes, sure. Absolutely.”

We arrived on time and just as I was paying for the book, Ghosh entered the bookstore with his wife, the writer Deborah Baker. He looked tired, his shoulders drooping, but who cared, this was the first time I was seeing a writer I had loved in the flesh.

There was a short reading from the book, and as the compere read out an exchange from one of the first few pages of the hardcover, Ghosh stared into the distance with a frown on his face.

At last, the crowd was asked to queue for the signings. Ghosh rummaged in his pocket for a second and brought out a metal pen. The stage was set.

I noticed that everyone was saying something to Ghosh to which he was gently nodding and responding to. I briefly mulled over the line, “The character Mangala Bibi from The Calcutta Chromosome still wakes me up at nights,” but decided against it, in what was singularly the only occasion where I have looked before I leapt.

The woman in front of me spelt her name out for him, “J-I-N-I-A.”

“Oh, what a beautiful name, is there a particular reason behind it?” asked Ghosh.

“I don’t know, my father just like the flower I think,” she said.

“Oh, haha,” said Ghosh.

“Can you mention the date, please, sir?” she said.

“Of course, of course.”

Next was I. Before Ghosh even opened to the page, I had said, “Good evening, sir, my name is Soumashree. S-O-U-M-A-S-H-R-E-E” in one breath.

Ghosh looked wearily at me and then said, “S-O-U?”

“M-A-S-H-R-E-E.”

In two seconds it was over. So I clutched at the only straw available.

“Sir, can you put in the date please, sir?”

He had already closed the book.

“Sure, absolutely.”

“Thank you so much.”

“Thank you.”

I returned to my mother, standing at a distance, brandishing the book half expecting people in the mall and on the streets to come running up to me to check out the signed copy. Once home, I ambled into my room where my teacher was hunched over the table, asleep.

“How do you feel?” asked miss.

“Much better,” I said and sighed.

I read Sea of Poppies, turning often to the first signed page. It was rich and homely—a Bengali book written in English.

Exactly two years later, on the same day, I would enter my university’s famed English department. Once inside, I read Amitav Ghosh with renewed vigour in classes where The Hungry Tide was taught with Rainer Maria Rilke‘s Duino Elegies, where passages of In an Antique Land made our professor’s voice quiver, and where The Shadow Lines returned in classes devoted to the larger narrative of nation formation and rupture.

Exactly two years later, on the same day, I would enter my university’s famed English department. Once inside, I read Amitav Ghosh with renewed vigour in classes where The Hungry Tide was taught with Rainer Maria Rilke‘s Duino Elegies, where passages of In an Antique Land made our professor’s voice quiver, and where The Shadow Lines returned in classes devoted to the larger narrative of nation formation and rupture.

I was deep into the tumult of daily college life when the second part of the Ibis trilogy, River of Smoke, was upon us in 2011. This book, too, was to release in the same bookstore at the same mall. This time, I noticed from the newspaper ads that Ghosh was to speak in at least three other city venues during the concentrated time period in which he was stopping at Calcutta while touring the country with the book.

I was deep into the tumult of daily college life when the second part of the Ibis trilogy, River of Smoke, was upon us in 2011. This book, too, was to release in the same bookstore at the same mall. This time, I noticed from the newspaper ads that Ghosh was to speak in at least three other city venues during the concentrated time period in which he was stopping at Calcutta while touring the country with the book.

It had rained heavily on the day, and when I reached the bookstore after a robust fight with my boyfriend, it was entirely full. Ghosh would be in conversation with the maverick Rimi B. Chatterjee—a novelist and my writing professor at university. This time I knew most of the crowd assembled. Classmates, professors, lecturers, friends who studied literature in other colleges, and my boyfriend all milled about in a spirit of great celebration while we waited for Ghosh.

He eventually arrived, looking tired. A classmate whispered, “I almost feel bad that he has to sign so many copies now.” A discussion ensued. A more lively and interactive one than the one in 2008, but a discussion which Chatterjee had to repeatedly maneuver back to the topic of the book, thanks to the garrulous Calcuttan’s natural inclination to begin a long, winding lecture whenever a microphone is handed to him. At the end of a young man’s nervous but long-winded account of how he felt Ghosh should have navigated the boatman’s experience in The Hungry Tide better, the audience had grown agitated and murmured dissent. Ghosh was unperturbed. He had a slight frown but he thanked the man for his opinion and answered him at length.

When the magic hour of the book signings arrived, the bookstore staff handed us small pieces of paper.

“What for?”

“Write your name on it.”

I willingly wrote all 16 letters of my full name on it before realizing that the paper was to act as reference for Ghosh as he signed our names on the books. They would speed the process and eliminate the ordeal of him having to figure out the hurriedly announced spellings of our names over the din.

When my turn came, I handed him the paper and he unquestioningly wrote down my whole name on the book. I remember thinking if he remembers writing the same name down years ago, and then thinking of all the names that he has had to write in the meantime.

“Do you study in college?” he abruptly asked.

“I…yes,” I stammered, looking around wildly for a professor to substantiate this.

“Oh. Where?” Ghosh asked.

“At Jadavpur,” I barely replied.

“Oh. Good,” said Ghosh, looking in Chatterjee’s direction, acknowledging my need to have a professor verify my presence.

“Thank you,” I said.

“Well, thank you,” he replied.

I showed my boyfriend the book. The next morning, we spotted ourselves in photographs of the book release that were published in newspapers.

Time flew, I got two degrees in English literature and moved to Bangalore to work as a journalist for the tabloid pages of an English daily. Tabloid it was, but within its pages, headlined by only the most conventionally beautiful of women, it had detailed theatre reviews, culture pages, and no fewer than a weekly 1,000 words devoted to literature. I did not like my job and its only perk was these book and theatre stories that we got to write. I wrote these with a lot of vigor, but as a new entrant into the city’s tabloid circle, I never quite got into the groove of receiving the first promotional email of any event and was routinely beaten to the juicy book reviews and theatre previews by my colleagues.

One Wednesday in June 2015, my boss suddenly asked, “Do you want to interview Amitav Ghosh day after tomorrow?”

“What?”

“His Flood of Fire is releasing and I had not noticed the email,” she said. “I will forward it to you. Make sure you read some of his work before going.”

“His Flood of Fire is releasing and I had not noticed the email,” she said. “I will forward it to you. Make sure you read some of his work before going.”

I festered in silence. The email entered my inbox. I called the contact it mentioned at Penguin Random House, Ghosh’s publisher.

“It’s a bit late in the day, isn’t it?” she said.

“I know, but I was just delegated the interview,” I said.

“Take this guy Varun’s number. He’s in charge of the interviews,” she said.

I called this guy Varun.

“Your newspaper’s Chennai office is doing an interview for the national Sunday page review already,” he said.

“I was hoping to speak with him about his particular experience of Bangalore,” I lied.

“Well, that’ll be difficult. Amitav is not doing very well, he is rather ill, so even if I could have squeezed you in under normal circumstances, I don’t think I’ll be able to do that now,” he said.

I almost laughed in relief.

“I understand. Please give him my best.”

“Thanks a lot for being so easy to convince, Soumashree. Please do come at the book launch event.”

“Oh sure, I will.”

The pressure lifted. What questions could I frame for a 10-minute long interview with Ghosh? What questions need one ask the custodian of one’s literary consciousness?

The next day, I went to the boss and told her that we had missed securing a slot in a day’s interactions with Ghosh.

“Do try to go for the evening launch tomorrow, though,” the editor said.

I opened the email again and stared at the location. It was in an atrium at a five-star hotel at the center of the city. Having edited the “Party” pages of the newspaper and attended one too many nightly events where Bangalore’s “it” crowd converged to be photographed, I knew immediately what kind of evening this would be. A staple crowd would turn up to be photographed, they would make small talk and disperse like they dispersed in every other party, no matter what the occasion.

Ghosh had passed from the ambit of mall store book releases into the “entry by invitation only” exclusivity. This was no bookstore. This launch would have no crowd of talkative people so neck-deep in the ethos of Hungry Tide that they forget that there is an audience around them. I was livid. I did not go.

A day later, the lifestyle editor of our newspaper told us that Ghosh was extremely polite and had signed all her books with great courtesy.

“He is a Bengali, like you. Have you read anything by him?”

I raged in silence at a writer climbing the last step of impenetrability and moving out of the reach of the people—his people. How dare the Ghosh of the attic afternoons, the Ghosh whose Burma reflected the one my father spent the best three years of his life, the Ghosh who wrote characters like the softly rebellious Tridib whom we find in every single Bengali home…how dare he betray the shared smallness of our Calcutta to the in-your-face prosperity of Bangalore.

Does the literature that rises from Calcutta belong to the city alone? Yes, I told myself.

I was ashamed even then of feeling this way. But while the likelihood of Ghosh himself announcing that he would like to have a book launch at a hotel instead of a bookstore was pretty slim, I seethed and vowed never to buy this third book.

In 2016, I moved back to Calcutta to work on my own novel. And that year, Ghosh released The Great Derangement. Every publication brought out an interview. I purchased all the magazines that had them. Eventually, I saw a circulating flier on Facebook saying Ghosh would come to a discussion at my university. “All were welcome.”

In 2016, I moved back to Calcutta to work on my own novel. And that year, Ghosh released The Great Derangement. Every publication brought out an interview. I purchased all the magazines that had them. Eventually, I saw a circulating flier on Facebook saying Ghosh would come to a discussion at my university. “All were welcome.”

Events and talks follow a particular tradition at my university. At any given day, somewhere on the campus, a crowd would form around a world-famous academic, leader, writer, or performer visiting then. And the great thing about the crowd was that it was never limited to the students and teachers of the relevant department or even the university. The gates were open to all, all events were open to all.

I reached the hall on a sunny afternoon and could barely open the door enough to slip in. It was entirely full. Ex-students, researchers, professors, ex-professors, organizers, absolute strangers, and current students occupied every inch of the floor and sweated through the air conditioning. Some of the seat handles even had a student on it, crouching low, so as to not obstruct the view of the people behind him or her. The windowsills were occupied. Three people sat on the small bench meant for the sound guy. I sat down on the floor, along with nearly 30 others. Ghosh sat relaxed, and then took out his smartphone and took a photograph of us.

He was in conversation with a professor of comparative literature and one of oceanography. With all the laughter, the effortless discussion, and the way Ghosh referred to how much he had enjoyed an earlier talk at Jadavpur University—a talk in 2008, on the same day when he had gone to the bookstore where I would first see him—he was making amends for releasing Flood of Fire in a swank hotel. The microphone faltered, the room grew hot, but the deep conspiracy of a summer afternoon on Calcutta was at work once again. The writer was ours once again, putting a lid on my jealousy.

Amitav Ghosh would later tweet the photograph of the event. I am there.

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons.