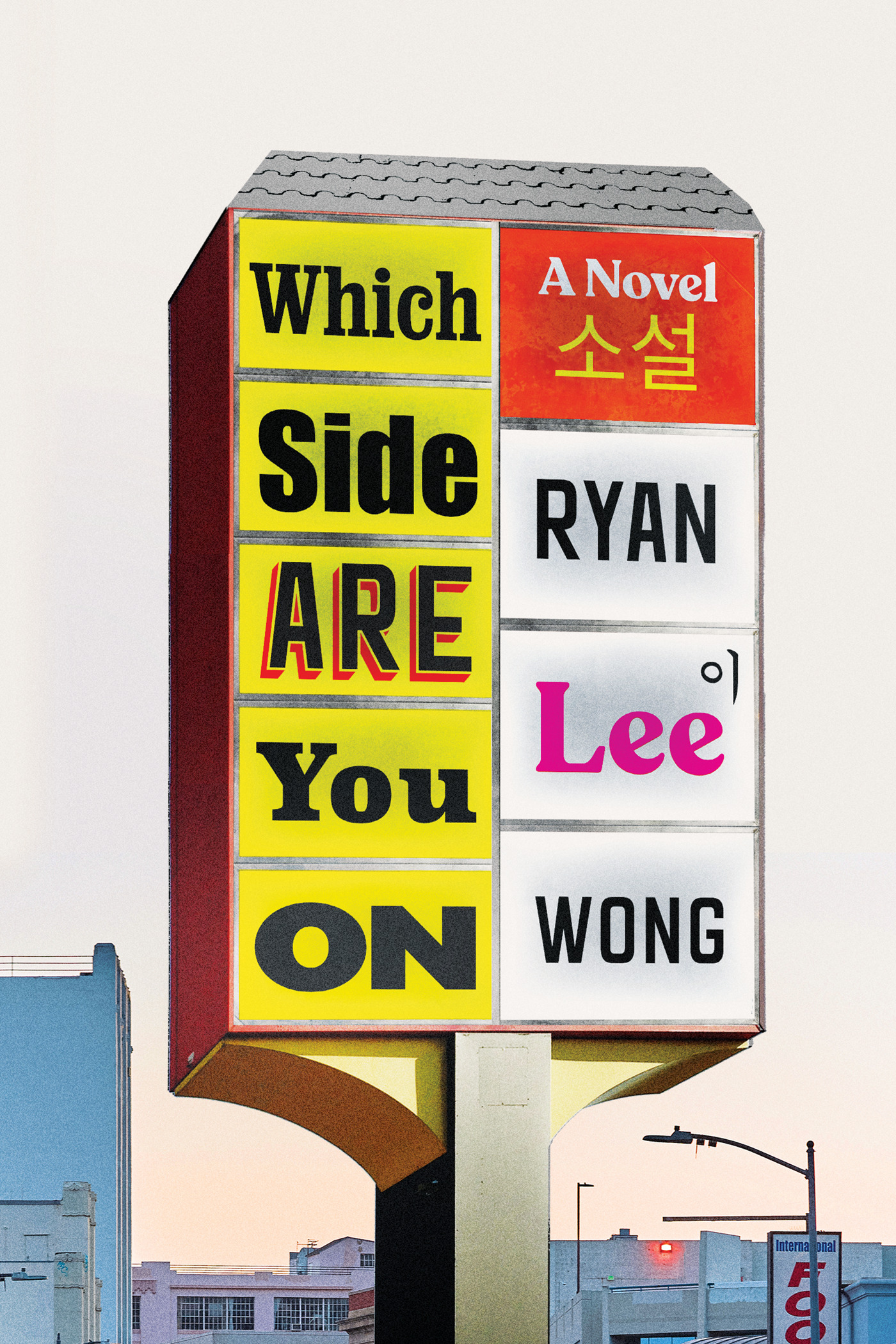

At the beginning of Ryan Lee Wong’s debut novel, Which Side Are You On, our narrator Reed wants to drop out of his Ivy League college to become a full-time activist in New York City’s Black Lives Matter movement. On a visit back to his parents in L.A., he goes to his mother for her advice—and is surprised by what he discovers. Which Side Are You On is a portrait of the activist as a young man, a coming-of-age story with activism at its center; it is both a biting satire of contemporary politics and a poignant family drama. As a novelist, Wong draws upon a wealth of resources—from his experiences as an activist and research into Asian American movements to his own family history, which includes his mother’s work with Black-Korean coalitions in the 1980s. I had the opportunity to connect with Wong over the phone, where we chatted about the role of pleasure in activism, the state of Asian America, and why nobody walks in L.A.

Jaeyeon Yoo: Where did this novel begin?

Ryan Lee Wong: The story came first. I wanted to tell a story based on my experiences and the activist’s role during the time of the first Black Lives Matter movement, and to also tell something based on my mother’s life story around Black-Korean organizing in the 1980s. I wanted to focus on the cycle of history that those two moments represented. I knew that fiction was the outlet because of how emotional and personal the topic was—and how, even though it involves politics and history, the heart of the story to me was ambiguous in a way that I felt only fiction could capture. I really learned to write fiction in order to write this book.

I tried a few different versions of the story, some of which were much more focused on the character of the mother. One version was even set in the 1980s, which was much more traditional historical fiction. But then, I also wanted the book to be about an activist’s coming-of-age. A certain turn that I made, and I think a lot of activists make, is from seeing the world in very stark, unforgiving terms to allowing a little more ambiguity and compassion, more of a heart-connection to the work and to other people. This turn is why Reed started to become a major part of the story.

JY: I know your other work also includes curating exhibitions which share clear themes of Asian American activism. Could you talk more about how your artistic practices interact with one another?

RLW: In a way, all my work is a form of self-discovery—of finding the histories that shaped me. With my curatorial and archival work, I explored this question of “What is Asian America?” Asian American is the term that I most identify with; yet, even 10 years ago, the kind of collective understanding of Asian America had been stripped away of its political roots. Most of the people I talked to, myself included, didn’t really know this story of radical Asian America, or Asian American activist history—which quite literally gave us the term “Asian America.” Just as this book was a way for me to tell the story of a personal and political activist history, my curatorial work was a way for me to tell the story of the bigger political formations that made me.

JY: What does being Asian American mean to you, then?

RLW: That’s a question I’m always asking and I’ll always be asking. I think that if there’s one simple answer on what Asian America “is,” there’s something missing. For me, Asian America only makes sense in terms of a political identity. It doesn’t mean anything unifying in terms of culture or language; it really was a term chosen by a group of activists. I take that as an invitation to re-examine the identity again and again, in each historical moment. The political situation now mirrors what was happening in 1968, but it’s obviously not the same. Asian America is a living, breathing legacy.

JY: You gesture to clear historical and political influences within the novel; what were some major aesthetic influences for Which Side Are You On?

RLW: I kind of came into this whole lineage of these Jewish leftist women writers. I think that might be because there are many parallels between the way Jewish folks were radicalized in the 50s through the 70s, and then how Asian Americans came into political consciousness in the 60s to the 80s. So I was reading people like Vivian Gornick, Natalia Ginzburg, Grace Paley. Then, as a Korean American with a mother who came over from Korea as a teenager in the early 70s, I was interested in how to capture that unique kind of voice. My mother went to Berkeley, then quickly picked up this mix of Marxist language, Black vernacular, and activist college students’ speech—alongside a Korean accent and a whole lot of cussing. A lot of these characters in Grace Paley’s stories, for example, were mixing Yiddish and Bronx socialist language, and they’re really smart, really funny. That was one aesthetic lineage. Another aesthetic interest were these quiet first-person stories, like Rachel Cusk’s Outline trilogy, in which the action happens over a matter of days. I found it an interesting formal device. I’ve always found it fascinating, how my experience of learning about historical trauma almost always happens in these very middle-class settings. We’ll be driving a car and someone will say, “Oh, you know what happened with your auntie and her first husband?” That was just true to my experience, so that’s why I had to leave behind the more traditional, third-person historical way of telling things.

RLW: I kind of came into this whole lineage of these Jewish leftist women writers. I think that might be because there are many parallels between the way Jewish folks were radicalized in the 50s through the 70s, and then how Asian Americans came into political consciousness in the 60s to the 80s. So I was reading people like Vivian Gornick, Natalia Ginzburg, Grace Paley. Then, as a Korean American with a mother who came over from Korea as a teenager in the early 70s, I was interested in how to capture that unique kind of voice. My mother went to Berkeley, then quickly picked up this mix of Marxist language, Black vernacular, and activist college students’ speech—alongside a Korean accent and a whole lot of cussing. A lot of these characters in Grace Paley’s stories, for example, were mixing Yiddish and Bronx socialist language, and they’re really smart, really funny. That was one aesthetic lineage. Another aesthetic interest were these quiet first-person stories, like Rachel Cusk’s Outline trilogy, in which the action happens over a matter of days. I found it an interesting formal device. I’ve always found it fascinating, how my experience of learning about historical trauma almost always happens in these very middle-class settings. We’ll be driving a car and someone will say, “Oh, you know what happened with your auntie and her first husband?” That was just true to my experience, so that’s why I had to leave behind the more traditional, third-person historical way of telling things.

JY: You mentioned the funniness in some of these voices—I really enjoyed the humor in your novel. Reed realizes the importance of fun, particularly within activism, during the course of the novel; I wonder if you had more to say about the role of pleasure within revolution.

RLW: We’re in this exciting moment where ideas like pleasure and self-care and joy have really entered the toolkit of activism. For examples, Rebecca Solnit just wrote Orwell’s Roses, and adrienne marie brown’s Pleasure Activism. Most frontline activist work is incredibly hard. It’s hard on the mind, it’s hard on the emotions and the body. Ten years ago, I definitely valorized people who were good at enduring difficulty. It was something that I aspired to, but this can (although not always) turn into a sort of martyrdom complex of valorizing the people who suffer the most. In the novel, one of the main lessons the mother learned from her intense experiences in activism, was that level of difficulty is not something you can face over and over again for years—and come out okay.

RLW: We’re in this exciting moment where ideas like pleasure and self-care and joy have really entered the toolkit of activism. For examples, Rebecca Solnit just wrote Orwell’s Roses, and adrienne marie brown’s Pleasure Activism. Most frontline activist work is incredibly hard. It’s hard on the mind, it’s hard on the emotions and the body. Ten years ago, I definitely valorized people who were good at enduring difficulty. It was something that I aspired to, but this can (although not always) turn into a sort of martyrdom complex of valorizing the people who suffer the most. In the novel, one of the main lessons the mother learned from her intense experiences in activism, was that level of difficulty is not something you can face over and over again for years—and come out okay.

JY: How about happiness? Does it play a similar role that pleasure does in revolution, or is it something a little different?

RLW: This is where the activist conversation gets mixed in with the diaspora conversation. There’s a fine line between pursuing happiness and receiving joy, and those things can get very mixed up very quickly. I think pursuing happiness can become this individualistic, materialistic, capitalistic gain: a kind of consumerist adoption of the American Dream. This is something that I see as a pattern in my family and many other immigrant families, where part of the whole reason for coming to America becomes the accumulation of material comfort, which becomes a way of proving one’s happiness. In the novel, even as I want to show the mother’s wisdom in learning to care for herself and accepting fun and joy, I think there’s also a bigger conversation of when that tips a little bit into materialism. A lot of the conversations between the three generations—the grandmother, the mother, and Reed—are about trying to navigate these remarkably different subject positions; each of them has a completely different idea, on the right balance between joy and self-denial, aestheticism and materialism. The grandmother is the most materialistic of the three and maybe also had the most painful life. Reed keeps wanting to slot people into these categories—this person either understands or they don’t—but the more he learns about his grandmother, the more it complicates his desire to do that, because her life story is so outside of his ability to comprehend.

JY: It sounds like you worked a lot from your mother’s stories as you wrote the novel. I appreciated the line you walked in the novel, of showcasing how Reed’s desire to learn from his parents’ activism has this dual aspect: one is of “commercializing” (the social capital, if you will, such as how he first kept thinking of ways to package his mother’s stories), the other is a genuine need to learn from one’s history. How do you deal with this tension, of writing about something and also feeling the pressure of “marketing” it?

RLW: That’s so real. I think it comes down to a question of intention. On the one hand, Reed has a real personal desire to learn his mother’s story and to make sense of his own life. At the same time, there’s this other part of him that’s watching and seeing how he can turn this into a toolkit that he can share with his activist friends. Of course, this is a metaphor for the writer’s dilemma: this desire to transform everything in your life, especially the painful things, into our way of making meaning of it, making it legible to yourself and others. Potentially, it can even turn that art into something commercial. Reed has to struggle with there being no perfect ethical way to navigate this, as does the writer.

Reed’s intentions, in the beginning, are a little unskillful. He’s trying to extract his idea of the right story. And if that is one’s intention, then it’s going to lead to people getting hurt and betrayed. But I think the more he’s able to be receptive and feel the full complexity of heartache and failure and joy—the more that complexity will lead him to the right answer. Similarly, by publishing this book, what I really aspire to is to let the reader have their own takeaways and their own conclusions. To be perfectly candid, when I started writing this book in about 2016, I definitely wanted the reader to agree with me. I had a very particular viewpoint—in that sense, I was much more like Reed.

JY: On a sort of meta level, your author’s journey mirrored Reed’s! I was interested by the linguistic trends that you point out in the novel, such as how Reed and his mother have different activist “dialects.” What, for you, is the role of language within these waves of varying activist cultures?

RLW: When you look at many activist movements, if not most, poetry is almost always in the mix, whether it’s activist leaders reading poetry or activists writing poetry. Poetry is essentially the creation of new language, or new formations of language, to name things that haven’t been. That’s very similar to activism, which is often trying to bring visibility to or to change things that haven’t yet been named. In that sense, language and activism are inseparable. They’re almost two expressions of one thing. And that’s why—especially now—movements are synonymous with their language: Black Lives Matter, #MeToo, the 99%. It’s because we need that language to help us make sense of the world. I’m a Zen practitioner, and there’s this quotation from Zen teachers, which goes something like, “Birds live in the air, fish live in the water, and humans live in language.” Language is the substance of our lives, and activism is a way to reform that language, to help us see the possibilities. There are a lot of jokes about activist language in the book, but it’s because every generation has to find its own language. One generation’s language will probably sound a little strange or foreign or funny to another generations, which is actually appropriate, because it is a different language and different political moment.

JY: You’ve mentioned the emphasis on conversations and the timeline—were there other specific like formalistic choices that you made, to heighten the themes of what you’re trying to do in this book?

RLW: I’ve always admired novels that are built on the flaneur tradition—of someone walking around, often men, in public spaces. There’s a whole joke in the novel about Ulysses and James Joyce. Part of the reason that’s in there is because I realized that Ulysses couldn’t happen in L.A.—no one walks there! I don’t know if you’ve spent much time in L.A., but if you walk for any long stretch of time, people look at you weird, you feel weird, and the sidewalks are so empty. You’re on these big streets that are pedestrian-unfriendly under the sun. It just feels like you’re doing this insane desert crossing. So my question to myself was, How do you have a character struggling with ideas and conversations, with minimal external action in this car-driven culture? That’s why there’s so much about cars, meeting up in cars, and these really weird in-between spaces that are particular to L.A., like the strip mall. There’s a lot of time spent in parking lots in the novel, because that is where life happens in L.A. This was my response to the flaneur tradition.

RLW: I’ve always admired novels that are built on the flaneur tradition—of someone walking around, often men, in public spaces. There’s a whole joke in the novel about Ulysses and James Joyce. Part of the reason that’s in there is because I realized that Ulysses couldn’t happen in L.A.—no one walks there! I don’t know if you’ve spent much time in L.A., but if you walk for any long stretch of time, people look at you weird, you feel weird, and the sidewalks are so empty. You’re on these big streets that are pedestrian-unfriendly under the sun. It just feels like you’re doing this insane desert crossing. So my question to myself was, How do you have a character struggling with ideas and conversations, with minimal external action in this car-driven culture? That’s why there’s so much about cars, meeting up in cars, and these really weird in-between spaces that are particular to L.A., like the strip mall. There’s a lot of time spent in parking lots in the novel, because that is where life happens in L.A. This was my response to the flaneur tradition.

JY: Yeah, I appreciated the James Joyce reference, especially Reed’s reflection: “Maybe, though, I’d turned that fight [against white authors] into a sort of laziness. I was used to saying damning about the great white canon and everyone else in the room nodding, whether or not I or they had read it.” In that vein: how do you engage with the canon? How do we build on other works of art that already exist, without lazily condemning everything?

RLW: Around the time I started this book, I did this little experiment where, for a whole year, I only read books by writers of color. It was extremely useful because it helped me reorient my entire idea of literature. Here was the thing: I didn’t feel like I was missing anything. And then, what happened after that experiment? I was able to go back and really ask the question: What would it mean to read one of these great writers in the canon? What was great was that I was able to see them not as enemies or people on some pedestal, but as resources. These writers are often people who had the privilege to sit there, to really think through and play with questions and form—in a way that I could learn from. One summer, I read the first two books of Proust in this way, and it was great. This dude really played with sentences all day. If I could learn from the way one’s interiority might be shaped by that kind of experience, I could sidestep the whole question of Is this the best thing ever written? Or is it just some oppressive, self-indulgent white man? Those questions seemed less relevant, when I was just really reading to learn.

JY: That’s really helpful. Your novel does embrace ambiguity, as we discussed, but I guess I’m going to be a little bit like Reed and ask, for the final question: do you have any advice for aspiring activists? Anything you didn’t get to say in the novel?

RLW: This is something that’s maybe not explicit in the novel, but self-knowledge is the key to activism for me. Activist figures that I really resonate with and admire the most were effective and inspiring because they had done an immense amount of inner, quiet, and reflective work to understand their particular role in history and their community. If you don’t have that kind of self-knowledge, you quickly spiral into the very neurotic position of “Oh well, the world is burning, and do I focus on the environment? Or focus on abortion rights, or on racial oppression?” And then this spiral makes people freeze. But more people understand their particular seats and the greater picture, they understand where to act from.