Adrian Tomine was a teenager when his self-published comic Optic Nerve first received attention, and in the years since he’s carved out a career as an illustrator, occasional New Yorker cover artist, and one of the great cartoonists of his generation. So much of his work revolves around silence, unexpected encounters, characters grappling with time and change. Tomine has made short nonfiction projects before, but his new book The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist, which is designed to look like a journal, with pages in a simple grid layout, is as revelatory and complex as anything he’s ever made.

Adrian Tomine was a teenager when his self-published comic Optic Nerve first received attention, and in the years since he’s carved out a career as an illustrator, occasional New Yorker cover artist, and one of the great cartoonists of his generation. So much of his work revolves around silence, unexpected encounters, characters grappling with time and change. Tomine has made short nonfiction projects before, but his new book The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist, which is designed to look like a journal, with pages in a simple grid layout, is as revelatory and complex as anything he’s ever made.

The book consists primarily of awkward moments, slights, humiliations, uncomfortable scenes that have stayed with him over the years. At the same time, Tomine drops the reader into each scene, jumping ahead months or years, his circumstances changing sometimes radically with few clues as to the details. The book, like in all his work, focuses on small moments and interactions that so often define our lives, and we see in these pages how Tomine thinks about and sees the world. It’s a moving portrait of the passage of time, the struggles of the artistic life, and the joys of fatherhood.

The Millions: You’ve made nonfiction comics before, but this is a very different kind of book for you. What made you interested in making something so different?

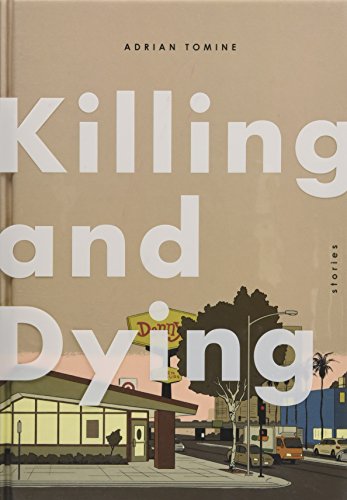

Adrian Tomine: For that very reason. Since around the time of my book Shortcomings I started trying to make each subsequent book in response to the previous one. Not wanting to repeat myself, at least in terms of form or tone. I felt like after finishing Killing and Dying—which was fiction, full color, short stories—this seemed like the natural alternative to that.

Adrian Tomine: For that very reason. Since around the time of my book Shortcomings I started trying to make each subsequent book in response to the previous one. Not wanting to repeat myself, at least in terms of form or tone. I felt like after finishing Killing and Dying—which was fiction, full color, short stories—this seemed like the natural alternative to that.

TM: In the final scene of the book you depict yourself getting this idea and starting to make the book. Was that how it started? Did you have this rough idea of the book more or less when you first sat down?

AT: I started an early version of it in a sketchbook and later realized that that might be my next book. Because I’ve had this job since I was a kid basically, whenever something negative happens in my life there’s some well-meaning person who says, it’s all good material. Usually it annoys me at the time, but I have to play along gamely. This book is a case of trying to make that true. Accumulating memories and experiences that might have been painful or annoying at the time, and trying to take control of them and make them into something that might be enjoyable or entertaining to other people. Including myself.

TM: Do most of your projects start in your sketchbook?

AT: To a degree. If you look at some other cartoonists’ sketchbooks you see that it’s their subconscious put down on paper. They’re compulsive in their sketchbook work, and they just open up their brain on the paper. Over the years I’ve moved away from that. Partly for practical reasons. I’ve got two young daughters I’m spending a lot of my days with, so I don’t have the time to mindlessly doodle the way I used to. But you can find evidence of all the books and stories in my sketchbooks. It’s not so much I stumbled upon it in the sketchbook and turned it into a book, but a lot of the work was done in my mind and getting it down in a sketchbook was a way of not forgetting it.

TM: You’re not making a whole book or even necessarily stories in the sketchbook, it’s just where they start.

AT: This one was different because I did start to sketch out very rough versions of some of the incidents that I described in the book. But it was much more rough than the printed version.

TM: The design of the book resembles a sketchbook or diary. And maybe this is obvious because its nonfiction, but it felt like it was your most personal book.

AT: It is. I think people will pick up on that right off the bat, as you said, because of the format and the main character is supposed to be me. The challenge for me with this book was to make an explicitly autobiographical story try to approach the level of revelation or confession that I’ve embedded in my fictional books. I feel like for my personality and my style of art that maybe these fictional stories like Shortcomings or Killing and Dying are the best way for me to express myself. When I took up the challenge to do an autobiographical book I didn’t want it to be like the Scenes from an Impending Marriage book, which was autobiographical but very lightweight and maybe a little bit generic in terms of how deep in delved. If I was going to attempt this, I wanted to get into a deeper level of introspection.

AT: It is. I think people will pick up on that right off the bat, as you said, because of the format and the main character is supposed to be me. The challenge for me with this book was to make an explicitly autobiographical story try to approach the level of revelation or confession that I’ve embedded in my fictional books. I feel like for my personality and my style of art that maybe these fictional stories like Shortcomings or Killing and Dying are the best way for me to express myself. When I took up the challenge to do an autobiographical book I didn’t want it to be like the Scenes from an Impending Marriage book, which was autobiographical but very lightweight and maybe a little bit generic in terms of how deep in delved. If I was going to attempt this, I wanted to get into a deeper level of introspection.

TM: I was thinking about how I know many cartoonists have similar stories. In thinking about what stories to include and how to approach it, were you thinking about not just how personal you wanted it to be, but how relatable?

AT: The first priority for me is to always make it personal—and make it true to my own experiences. With an autobiographical book like this I almost have to trick my mind into not thinking about an audience much and not worry about how it’s going to be received. Along with that, not worry about who’s going to relate to it. I’ve always said that I’m constantly trying to trick myself into the mindset of when I first started making comics as a teenager. I was making them purely for myself and when they ended up getting published, it was an extra bonus on top of the pleasure of having created them. Now that this book is going out in the world it’s interesting to hear from people who have had similar experiences or can relate to it. It’s really nice to hear from other artists of any kind that there’s something they found in common with these experiences. That’s a real reward for me.

TM: The book collects moments that are painful and awkward as you said, but they take a lot of different forms. There are moments of awkwardness, uncomfortable scenes of tour. There are moments of casual condescension towards comics. Odd moments of racism.

AT: Right now people are seeing excerpts from the story and it’s important to read it in full and get the context. A pretty long span of time progresses over the course of the book. There’s a lot of threads that keep coming up, but some of those things like the condescension towards comics is more in the earlier section of the book. Later on I’m at a New Yorker staff party. Hopefully when people read the whole book they’ll see there’s a primary action that’s happening in these very specific anecdotes, but with the passage of time there are background stories about the way that comics and cartoonists are treated. The fact that I go from sleeping on comic shop owners’ floors on tour to staying in hotels. You see my personal life evolve in the background. Suddenly there’s a kid—and then another kid. I hope that people will read an excerpt and think it’s funny but then get a little more out of it when they read it in the context of the full book.

TM: Narratively speaking, I couldn’t help but think that is one of the things that attracted you to this book and this idea. Getting to tell a story and depict time in a different way.

AT: I definitely started with the idea of all the anecdotes of being a professional cartoonist and then almost by default when you tell those stories in chronological order you have to show where you were living at the time or what the circumstances were. I started to see that it was hinting at other stories beyond the specifics of the personal embarrassments.

TM: The moment that really got to me was at the end. Where you imagined you were going to die but you weren’t thinking of work but of your family and that line “I guess I’m not as much of an ‘artist’ as I thought I was.” I’m sure you’ve heard this from others, but that was gutting.

AT: I’m flattered that people take that in an emotional way, but I wanted to present it as something of a relief. Something that might inspire people to give themselves some leeway. Especially among the cartoonists and artists I know, there’s such a pressure to be a great artist. And to be an artist above all else. When I had that experience, in a way, it was a pleasant thing. I took it as a positive thought to come to terms with who I really was and what my priorities are.

TM: Obviously having kids changed your life. Do you think it changed your work?

AT: I think so. Of course there’s no way to see the alternate path and see what the work would have been like otherwise, but my suspicion is yes. I was working on the book Killing and Dying over the course of both my kids’ births. It took me that long. I don’t think that the book would exist the way we know it if it weren’t for those experiences. Obviously the new book ends up being very explicitly connected to being a parent and being a husband.

I am totally open to the idea that some people might find it changed my work in a direction that isn’t to their taste. I think that the longing and loneliness of being a single guy in the Bay Area was really tied into the early years of my work. As a fan of other works of art, sometimes you want an artist to stay the same and keep delivering what you fell in love with about their work in the first place. I’m hoping there are some people who have aged and evolved alongside me and can still find something to enjoy now in my work. I can definitely understand if someone was just discovering my early work, they might be perplexed to see what I’m doing now.

TM: I understand that. I haven’t read 32 Stories in years, but I know I wouldn’t respond to it now like I did when I first read it in my early 20s.

AT: I sure don’t. [Laughs.]

TM: I know the film and story The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner, but where did your title come from?

AT: That’s a good question. I think people would be shocked to know how much time and energy I waste on my titles. It’s not like they’re that exciting or explosive, but for some reason I fret over them a lot. The other autobiographical book that I’ve done was the wedding book and the title was based on the Bergman film Scenes from a Marriage. I thought, maybe my autobiographical books will take their title from a much grander and more respected work of art and pervert it for my own uses. That helped narrow it down for me. In the end I found the title that I settled on was the best description of what was inside the covers for me.

TM: Do you like the film The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner?

AT: Yes. The funny thing is sometimes people will assume that those allusions are done in tribute to my favorite works of art. It’s not the case. I definitely am a fan of the things I’m riffing on, but I don’t know that that would be my favorite Bergman film—and I would be stretching the truth to say the film The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner is something I watch on a regular basis. The author of the source material, Alan Sillitoe, is great as well. A lot of times it’s just a balance of what’s something I can use that works best with my material. If the reference was something I really didn’t like, I probably would shy away from that.

AT: Yes. The funny thing is sometimes people will assume that those allusions are done in tribute to my favorite works of art. It’s not the case. I definitely am a fan of the things I’m riffing on, but I don’t know that that would be my favorite Bergman film—and I would be stretching the truth to say the film The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner is something I watch on a regular basis. The author of the source material, Alan Sillitoe, is great as well. A lot of times it’s just a balance of what’s something I can use that works best with my material. If the reference was something I really didn’t like, I probably would shy away from that.

TM: The story and the film were about running to find this physical and emotional escape from life. Being out there alone. It is the perfect metaphor.

AT: I feel a kinship with those themes. I’m sure actual athletes would scoff at the idea of comparing drawing comics to what they do. While I was working on the book I was thinking about cartoonist friends of mine who are older than me and have devoted their life to this. Trying to sort out the different feelings I had of admiration and thinking of them as role models, but at the same time feeling a little conflicted about whether I wanted to spend the next chunk of my life as devoted to the work as some of them had been. I think the loneliness aspect is open to interpretation. Especially now. I miss the solitary aspect of sitting in a room all day by myself and drawing. But I also would not want to miss out on a lot of the other aspects of my life that that might get in the way of that.

TM: The simple fact is that your life has changed, and your relationship to your work and to loneliness has changed.

AT: Now it’s a struggle to find alone time. I don’t have a separate studio. I’ve always worked from home. People will have their own opinions about it, but like I said it’s a bit of a relief when you can let yourself off the hook to a degree. “My friend did three graphic novels in one year and I didn’t do anything!” You can really drive yourself crazy sometimes.

TM: At end of the book, you’re questioning: Should I have spent my life on this? Do I want to keep doing it? It sounds like you’ve found an understanding and a balance.

AT: Yeah. I don’t know why it is exactly, but making these books is not easy for me. I’ve talked to other cartoonists and some feel the same way, but some have no idea what my problem is and don’t know why I can’t bash them out faster. Every time I’ve finished a book—probably going back to Shortcomings—there’s a part of me that thinks, this might be it. Maybe this is the last one. The idea of getting from that point to the finish point of another book just seems so daunting. I guess I’m in that same phase again where I finished this book—which in my mind was going to be a quick and easy one. I would make it sketchbook style, it would be autobiographical, and all these things that I thought would make it easier, but it still consumed my life more than I expected and took longer than I expected. It might be that I’m forcing myself to do something I’m not very suited to. But then I’m once again in this position of finishing another book somehow.

TM: Have you started thinking about or working on other ideas since?

AT: I have been. If I’m honest, the quarantine ended up falling at a fairly convenient time in my life. The book was done and was in the process of being printed. I gave me the opportunity to put being an artist on hold and assume the full-time responsibility of homeschool teacher–full-time playmate–personal cook–butler, all the jobs I’m doing for my kids every day. But I have a little bit of time here and there to do things. It’s nice to have this parallel career as an illustrator where I can take an assignment and be done with it in a week or two. I’m grateful that a few of those opportunities have popped up. Also I haven’t talked about it too much, but I’ve spent a fair amount of time the past few years screenwriting, which is another daunting and slow process. Over the last few years, there have been projects where someone else was adapting my work. Stuff where I’ve adapted my own work. Stuff with me generating something completely original. It’s been a little bit of everything. I should mention that none of it has come to fruition yet, so it’s possible that this will be the only record of that work!

TM: I’m glad all this happened at a moment where you could catch your breath.

AT: I’m grateful for that. My children don’t know it, but they are benefitting from the timing of this. I’ve always been in a bit of a bind about juggling my work and my parental obligations—especially since I work from home. I think this would have been a lot tougher if I was just finishing this book or trying to make a deadline on a book. Who knows what it will mean for my career or my income, but I’m trying to enjoy being a full-time parent as much as possible.