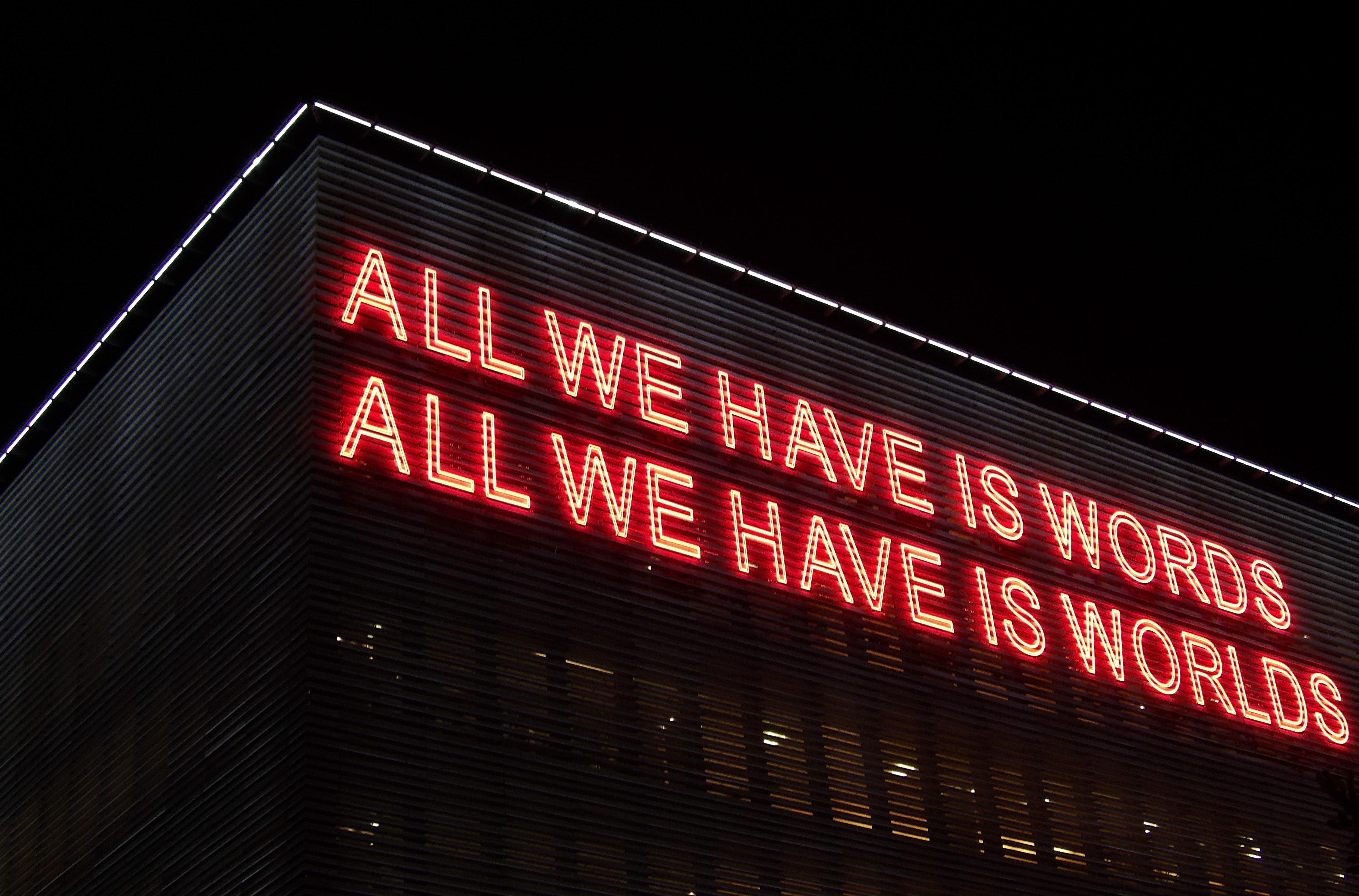

Blessedly, we are speakers of languages not of our own invention, and as such none of us are cursed in only a private tongue. Words are our common property; it would be a brave iconoclast to write entirely in some Adamic dialect of her own invention, her dictionary locked away (though from the Voynich Manuscript to Luigi Serafini’s Codex Seraphinianus, some have tried). Almost every word you or I speak was first uttered by somebody else—the key is entirely in the rearrangement. Sublime to remember that every possible poem, every potential play, ever single novel that could ever be written is hidden within the Oxford English Dictionary. The answer to every single question too, for that matter. The French philosophers Antoine Arnauld and Claude Lancelot enthuse in their 1660 Port-Royal Grammar that language is a “marvelous invention of composing out of 25 or 30 sounds that infinite variety of expressions which, whilst having in themselves no likeness to what is in our mind, allow us to… [make known] all the various stirrings of our soul.” Dictionaries are oracles. It’s simply an issue of putting those words in the correct order. Language is often spoken of in terms of inheritance, where regardless of our own origins speakers of English are the descendants of Walt Whitman’s languid ecstasies, Emily Dickinson’s psalmic utterances, the stately plain style of the King James bible, the witty innovations of William Shakespeare, and the earthy vulgarities of Geoffrey Chaucer; not to forget the creative infusions of foreign tongues, from Norman French and Latin, to Ibo, Algonquin, Yiddish, Spanish, and Punjabi, among others. Linguist John McWhorter puts it succinctly in  Our Magnificent Bastard Tongue: The Untold History of English, writing that “We speak a miscegenated grammar.”

Our Magnificent Bastard Tongue: The Untold History of English, writing that “We speak a miscegenated grammar.”

There is a glory to this, our words indicating people and places different from ourselves, our diction an echo of a potter in a Bronze Age East Anglian village, a canting rogue in London during the golden era of Jacobean Theater, or a Five Points Bowery Boy in antebellum New York. Nicholas Oster, with an eye towards its diversity of influence, its spread, and its seeming omnipresence, writes in Empires of the Word: A Language History of the World that “English deserves a special position among world languages” as it is a “language with a remarkably varied history.” Such history perhaps gives the tongue a universal quality, making it a common inheritance of humanity. True with any language, but when you speak it would be a fallacy to assume that your phrases, your idioms, your sentences, especially your words are your own. They’ve passed down to you. Metaphors of inheritance can either be financial or genetic; the former has it that our lexicon is some treasure collectively willed to us, the later posits that in the DNA of language, our nouns are adenine, verbs are as if cytosine, adjectives like guanine, and adverbs are thymine. Either sense of inheritance has its uses as a metaphor, and yet they’re both lacking to me in some fundamental way—too crassly materialist, too eugenic. The proper metaphor isn’t inheritance, but consciousness. I hold that a language is as if a living thing, or to be more specific, as if a thinking thing. Maybe this isn’t a metaphor at all, perhapswe’re simply conduits for the thoughts of something bigger than ourselves, the contemplations of the language which we speak.

There is a glory to this, our words indicating people and places different from ourselves, our diction an echo of a potter in a Bronze Age East Anglian village, a canting rogue in London during the golden era of Jacobean Theater, or a Five Points Bowery Boy in antebellum New York. Nicholas Oster, with an eye towards its diversity of influence, its spread, and its seeming omnipresence, writes in Empires of the Word: A Language History of the World that “English deserves a special position among world languages” as it is a “language with a remarkably varied history.” Such history perhaps gives the tongue a universal quality, making it a common inheritance of humanity. True with any language, but when you speak it would be a fallacy to assume that your phrases, your idioms, your sentences, especially your words are your own. They’ve passed down to you. Metaphors of inheritance can either be financial or genetic; the former has it that our lexicon is some treasure collectively willed to us, the later posits that in the DNA of language, our nouns are adenine, verbs are as if cytosine, adjectives like guanine, and adverbs are thymine. Either sense of inheritance has its uses as a metaphor, and yet they’re both lacking to me in some fundamental way—too crassly materialist, too eugenic. The proper metaphor isn’t inheritance, but consciousness. I hold that a language is as if a living thing, or to be more specific, as if a thinking thing. Maybe this isn’t a metaphor at all, perhapswe’re simply conduits for the thoughts of something bigger than ourselves, the contemplations of the language which we speak.

Philosopher George Steiner, forever underrated, writes in his immaculate After Babel: Aspects of Language and Translation that “Language is the highest and everywhere the foremost of those assents which we human beings can never articulate solely out of our own means.” We’re neurons in the mind of language, and our communications are individual synapses in that massive brain that’s spread across the Earth’s eight billion inhabitants, and back generations innumerable. When that mind becomes self-aware of itself, when language knows that it’s language, we call those particular thoughts poetry. Argentinean critic (and confidant of Jorge Luis Borges) Alberto Manguel writes in A Reader on Reading that poetry is “proof of our innate confidence in the meaningfulness of wordplay;” it is that which demonstrates the eerie significance of language itself. Poetry is when language consciously thinks.

Philosopher George Steiner, forever underrated, writes in his immaculate After Babel: Aspects of Language and Translation that “Language is the highest and everywhere the foremost of those assents which we human beings can never articulate solely out of our own means.” We’re neurons in the mind of language, and our communications are individual synapses in that massive brain that’s spread across the Earth’s eight billion inhabitants, and back generations innumerable. When that mind becomes self-aware of itself, when language knows that it’s language, we call those particular thoughts poetry. Argentinean critic (and confidant of Jorge Luis Borges) Alberto Manguel writes in A Reader on Reading that poetry is “proof of our innate confidence in the meaningfulness of wordplay;” it is that which demonstrates the eerie significance of language itself. Poetry is when language consciously thinks.

More than rhyme and meter, or any other formal aspect, what defines poetry is its self-awareness. Poetry is the language which knows that it’s language, and that there is something strange about being such. Certainly, part of the purpose of all the rhetorical accoutrement which we associate with verse, from rhythm to rhyme scheme, exists to make the artifice of language explicit. Guy Deutscher writes in The Unfolding of Language: An Evolutionary Tour of Mankind’s Greatest Invention that the “wheels of language run so smoothly” that we rarely bother to “stop and think about all the resourcefulness that must have gone into making it tick.” Language is pragmatic, most communication doesn’t need to self-reflect on, well, how weird the very idea of language is. How strange it is that we can construct entire realities from variations in the breath that comes out of our mouths, or the manipulation of ink stains on dead trees (or of liquid crystals on a screen). “Language conceals its art,” Deutscher writes, and he’s correct. When language decides to stop concealing, that’s when we call it poetry.

More than rhyme and meter, or any other formal aspect, what defines poetry is its self-awareness. Poetry is the language which knows that it’s language, and that there is something strange about being such. Certainly, part of the purpose of all the rhetorical accoutrement which we associate with verse, from rhythm to rhyme scheme, exists to make the artifice of language explicit. Guy Deutscher writes in The Unfolding of Language: An Evolutionary Tour of Mankind’s Greatest Invention that the “wheels of language run so smoothly” that we rarely bother to “stop and think about all the resourcefulness that must have gone into making it tick.” Language is pragmatic, most communication doesn’t need to self-reflect on, well, how weird the very idea of language is. How strange it is that we can construct entire realities from variations in the breath that comes out of our mouths, or the manipulation of ink stains on dead trees (or of liquid crystals on a screen). “Language conceals its art,” Deutscher writes, and he’s correct. When language decides to stop concealing, that’s when we call it poetry.

Verse accomplishes that unveiling in several different ways, chief among them the use of the rhetorical and prosodic tricks, from alliteration to Terza rima, which we associate with poetry. One of the most elemental and beautiful aspects of language which poetry draws attention towards are the axioms implied earlier in this essay – that the phrases and words we speak are never our own – and that truth is found not in the invention, but in the rearrangement. In Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics, the Russian literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin wrote that we receive “the word from another’s voice and filled with that other voice.” Our language is not our own, nor is our literature. We communicate in a tongue not of our own creation; we don’t have conversations, we are the conversation. Bakhtin reasons that our “own thought finds the world already inhabited.” Just as the organization of words into enjambed lines and those lines into stanzas demonstrates the beautiful unnaturalness of language, so to do allusion, bricolage, and what theorists call intertextuality make clear to us that we’re not individual speakers of words, but that words are speakers of us. Steiner writes in Grammars of Creation that “the poet says: ‘I never invent.’” This is true, the poet never invents, none of us do. We only rearrange—and that is beautiful.

Verse accomplishes that unveiling in several different ways, chief among them the use of the rhetorical and prosodic tricks, from alliteration to Terza rima, which we associate with poetry. One of the most elemental and beautiful aspects of language which poetry draws attention towards are the axioms implied earlier in this essay – that the phrases and words we speak are never our own – and that truth is found not in the invention, but in the rearrangement. In Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics, the Russian literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin wrote that we receive “the word from another’s voice and filled with that other voice.” Our language is not our own, nor is our literature. We communicate in a tongue not of our own creation; we don’t have conversations, we are the conversation. Bakhtin reasons that our “own thought finds the world already inhabited.” Just as the organization of words into enjambed lines and those lines into stanzas demonstrates the beautiful unnaturalness of language, so to do allusion, bricolage, and what theorists call intertextuality make clear to us that we’re not individual speakers of words, but that words are speakers of us. Steiner writes in Grammars of Creation that “the poet says: ‘I never invent.’” This is true, the poet never invents, none of us do. We only rearrange—and that is beautiful.

True of all language, but few poetic forms are as honest about this as a forgotten Latin genre from late antiquity known as the cento. Rather than inheritance and consciousness, the originators of the cento preferred the metaphor of textiles. For them, all of poetry is like a massive patchwork garment, squares of fabric borrowed from disparate places and sewn together to create a new whole. Such a metaphor is an apt explanation of what exactly a cento is – a novel poem that is assembled entirely from rearranged lines written by other poets. Centos were written perhaps as early as the first century, but the fourth-century Roman poet Decimus Magnus Ausonius was the first to theorize about their significance and to give rules for their composition. In the prologue to Cento Nuptialias, where he composed a poem about marital consummation from fragments of Virgil derived from The Aeneid, Georgics, and Eclogues, Ausonius explained that he has “but out of a variety of passages and different meanings,” created something new which is “like a puzzle.”

True of all language, but few poetic forms are as honest about this as a forgotten Latin genre from late antiquity known as the cento. Rather than inheritance and consciousness, the originators of the cento preferred the metaphor of textiles. For them, all of poetry is like a massive patchwork garment, squares of fabric borrowed from disparate places and sewn together to create a new whole. Such a metaphor is an apt explanation of what exactly a cento is – a novel poem that is assembled entirely from rearranged lines written by other poets. Centos were written perhaps as early as the first century, but the fourth-century Roman poet Decimus Magnus Ausonius was the first to theorize about their significance and to give rules for their composition. In the prologue to Cento Nuptialias, where he composed a poem about marital consummation from fragments of Virgil derived from The Aeneid, Georgics, and Eclogues, Ausonius explained that he has “but out of a variety of passages and different meanings,” created something new which is “like a puzzle.”

The editors of The Penguin Dictionary of Literary Terms and Literary Theory explain that while forgotten today, the cento was “common in later antiquity.” Anthologizer and poet David Lehman writes in The American Scholar that “Historically, the intent was often homage, but it could and can be lampoon,” with critic Edward Hirsch writing in A Poet’s Glossary that they “may have begun as school exercises.” Though it’s true that they were written for educational reasons, to honor or mock other poets, or as showy performance of lyrical erudition (the author exhibiting their intimacy with Homer and Virgil), none of these explanations does service to the cento’s significance. To return to my admittedly inchoate axioms of earlier, one function of poetry is to plunge “us into a network of textual relations,” as the theorist Graham Allen writes in Intertextuality. Language is not the provenance of any of us, but rather a common treasury; with its other purpose being what Steiner describes as the “rec-compositions of reality, of articulate dreams, which are known to us as myths, as poetry, as metaphysical conjecture.” That’s to say that the cento remixes poetry, it recombines reality, so as to illuminate some fundamental truth hitherto hidden. Steiner claims that a “language contains within itself the boundless potential of discovery,” and the cento is a reminder that fertile are the recombination’s of poetry that have existed before, that literature is a rich, many-varied compost from which beautiful new specimens can grow towards the sun.

The editors of The Penguin Dictionary of Literary Terms and Literary Theory explain that while forgotten today, the cento was “common in later antiquity.” Anthologizer and poet David Lehman writes in The American Scholar that “Historically, the intent was often homage, but it could and can be lampoon,” with critic Edward Hirsch writing in A Poet’s Glossary that they “may have begun as school exercises.” Though it’s true that they were written for educational reasons, to honor or mock other poets, or as showy performance of lyrical erudition (the author exhibiting their intimacy with Homer and Virgil), none of these explanations does service to the cento’s significance. To return to my admittedly inchoate axioms of earlier, one function of poetry is to plunge “us into a network of textual relations,” as the theorist Graham Allen writes in Intertextuality. Language is not the provenance of any of us, but rather a common treasury; with its other purpose being what Steiner describes as the “rec-compositions of reality, of articulate dreams, which are known to us as myths, as poetry, as metaphysical conjecture.” That’s to say that the cento remixes poetry, it recombines reality, so as to illuminate some fundamental truth hitherto hidden. Steiner claims that a “language contains within itself the boundless potential of discovery,” and the cento is a reminder that fertile are the recombination’s of poetry that have existed before, that literature is a rich, many-varied compost from which beautiful new specimens can grow towards the sun.

Among authors of centos, this is particularly true of the fourth-century Roman poet Faltonia Betitia Proba. Hirsch explains that one of the purposes of the cento, beyond the pedagogical or the parodic, was to “create Christian narratives out of pagan text,” as was the case with Proba’s Cento virgilianus, the first major Christian epic by a woman poet. Allen explains that “Works of literature, after all, are built from systems, codes and traditions established by previous works of literature;” what Proba’s cento did was a more literal expression of that fundamental fact. The classical past posed a difficulty for proud Roman Christians, for how were the faithful to grapple with the paganism of Plato, the Sibyls, and Virgil? One solution was typological, that is the assumption that if Christianity was true, and yet pagan poets like Virgil still spoke the truth, that such must be encoded within his verse itself, part of the process of Interpretatio Christiana whereby pagan culture was reinterpreted along Christian lines.

Daughter of Rome that she was, Proba would not abandon Virgil, but Christian convert that she also was, it became her task to internalize that which she loved about her forerunner and to repurpose him, to place old wine into new skins. Steiner writes that an aspect of authorship is that the “poet’s consciousness strives to achieve perfect union with that of the predecessor,” and though those lyrics are “historically autonomous,” as reimagined by the younger poet they are “reborn from within.” This is perhaps true of how all influence works, but the cento literalizes that process in the clearest manner. And so Proba’s solution was to rearrange, remix, and recombine the poetry of Virgil so that the Christianity could emerge, like a sculptor chipping away all of the excess marble in a slab to reveal the statue hidden within.

Inverting the traditional pagan invocation of the muse, Proba begins her epic (the proem being the only original portion) with both conversion narrative and poetic exhortation, writing that she is “baptized, like the blest, in the Castalian font – / I, who in my thirst have drunk libations of the Light – / now being my song: be at my side, Lord, set my thoughts/straight, as I tell how Virgil sang the offices of Christ.” Thus, she imagines the prophetic Augustan poet of Roman Republicanism who died two decades before the Nazarene was born. Drawing from a tradition which claimed Virgil’s Eclogue predicted Christ’s birth, Proba rearranged 694 lines of the poet to retell stories from Genesis, Exodus, and the Gospels, the lack of Hebrew names in the Roman original forcing her to use general terms which appear in Virgil, like “son” and “mother,” when writing of Jesus and Mary. Proba’s paradoxically unoriginal originality (or is its original unoriginality?) made her popular in the fourth and fifth centuries, the Cento virgilianus taught to catechists alongside Augustin, and often surpassing Confessions and City of God in popularity. Yet criticism of Proba’s aesthetic quality from figures like Jerome and Pope Gelasius I ensured a millennium-long eclipse of her poem, forgotten until its rediscovery with the Renaissance.

Rearranging the pastoral Eclogues, Proba envisions Genesis in another poet’s Latin words, writing that there is a “tree in full view with fruitful branches;/divine law forbids you to level with fire or iron,/by holy religious scruple it is never allowed to be disturbed./And whoever steals the holy fruit from this tree,/will pay the penalty of death deservedly;/no argument has changed my mind.” Something uncanny about the way that such a familiar myth is reimagined in the arrangement of a different myth; the way in which Proba is a redactor of Virgil’s words, shaping them (or pulling out from) this other, different, unintended narrative. Scholars have derided her poem as juvenilia since Jerome (jealously) castigated her talent by calling her “old chatterbox,” but to be able to organize, shift, and shape another poet’s corpus into orthodox scripture is an unassailable accomplishment. Writers of the Renaissance certainly thought so, for a millennium after Proba’s disparagement, a new generation of humanists resuscitated her.

Cento virgilianus was possibly the first work by a woman to be printed, in 1474; a century before that, and the father of Renaissance poetry Petrarch extolled her virtues in a letter to the wife of the Holy Roman Emperor, and she was one of the subjects of Giovani Boccaccio’s 1374 On Famous Women, his 106 entry consideration of female genius from Eve to Joanna, the crusader Queen of Jerusalem and Sicily. Boccaccio explains that Proba collected lines of Virgil with such “great skill, aptly placing the entire lines, joining the fragments, observing the metrical rules, and preserving the dignity of the verses, that no one except an expert could detect the connections.” As a result of her genius, a reader might think that “Virgil had been a prophet as well as an apostle,” the cento suturing together the classic and the Hebraic, Athens and Jerusalem.

Cento virgilianus was possibly the first work by a woman to be printed, in 1474; a century before that, and the father of Renaissance poetry Petrarch extolled her virtues in a letter to the wife of the Holy Roman Emperor, and she was one of the subjects of Giovani Boccaccio’s 1374 On Famous Women, his 106 entry consideration of female genius from Eve to Joanna, the crusader Queen of Jerusalem and Sicily. Boccaccio explains that Proba collected lines of Virgil with such “great skill, aptly placing the entire lines, joining the fragments, observing the metrical rules, and preserving the dignity of the verses, that no one except an expert could detect the connections.” As a result of her genius, a reader might think that “Virgil had been a prophet as well as an apostle,” the cento suturing together the classic and the Hebraic, Athens and Jerusalem.

Ever the product of his time, Boccaccio could still only appreciate Proba’s accomplishment through the lens of his own misogyny, writing that the “distaff, the needle, and weaving would have been sufficient for her had she wanted to lead a sluggish life like the majority of women.” Boccaccio’s myopia prevented him from seeing that that was the precise nature of Proba’s genius – she was a weaver. The miniatures which illustrate a 15th-century edition of Boccaccio give truth to this, for despite the chauvinism of the text, Proba is depicted in gold-threaded red with white habit upon her head, a wand holding aloft a beautiful, blue expanding sphere studded with stars, a strangely scientifically accurate account of the universe as the poet sings song of Genesis in the tongue of Virgil. Whatever anonymous artist saw fit to depict Proba as a mage understood her well; for that matter they understood creation well, for perhaps God can generate ex nihilo, but artists must always gather their material from fragments shored against their ruin.

In our own era of allusion, reference, quotation, pastiche, parody, and sampling, you’d think that the cento would have new practitioners and new readers. Something of the disk jockeys Danger Mouse, Fatboy Slim, and Girl Talk in the idea of remixing a tremendous amount of independent lines into some synthesized newness; something oddly of the Beastie Boys’ Paul’s Boutique in the very form of the thing. But centos proper are actually fairly rare in contemporary verse, despite T.S. Eliot’s admission that “mature poets steal.” Perhaps with more charity, Allen argues that reading is a “process of moving between texts. Meaning because something which exists between a text and all the other texts to which it refers and relates.” But while theorists have an awareness of the ways in which allusion dominates the modernist and post-modernist sensibility—what theorists who use the word “text” too often call “intertextuality”—the cento remains as obscure as other abandoned poetic forms from the Anacreontic to the Zajal (look them up). Lehman argues that modern instances of the form are “based on the idea that in some sense all poems are collages made up of other people’s words; that the collage is a valid method of composition, and an eloquent one.”

In our own era of allusion, reference, quotation, pastiche, parody, and sampling, you’d think that the cento would have new practitioners and new readers. Something of the disk jockeys Danger Mouse, Fatboy Slim, and Girl Talk in the idea of remixing a tremendous amount of independent lines into some synthesized newness; something oddly of the Beastie Boys’ Paul’s Boutique in the very form of the thing. But centos proper are actually fairly rare in contemporary verse, despite T.S. Eliot’s admission that “mature poets steal.” Perhaps with more charity, Allen argues that reading is a “process of moving between texts. Meaning because something which exists between a text and all the other texts to which it refers and relates.” But while theorists have an awareness of the ways in which allusion dominates the modernist and post-modernist sensibility—what theorists who use the word “text” too often call “intertextuality”—the cento remains as obscure as other abandoned poetic forms from the Anacreontic to the Zajal (look them up). Lehman argues that modern instances of the form are “based on the idea that in some sense all poems are collages made up of other people’s words; that the collage is a valid method of composition, and an eloquent one.”

Contemporary poets who’ve tried their hand include John Ashbery, who weaved together Gerard Manley Hopkins, Lord Byron, and Elliot; as well as Peter Gizzi who in “Ode: Salute to the New York School” made a cento from poets like Frank O’Hara, James Schuyler, and Ashbery. Lehman has tried his own hand at the form, to great success. In commemoration of his Oxford Book of American Poetry, he wrote a cento for The New York Times that’s a fabulous chimera whose anatomy is drawn from a diversity that is indicative of the sweep and complexity of four centuries of verse, including among others Robert Frost, Hart Crane, W.H. Auden, Gertrude Stein, Elizabeth Bishop, Edward Taylor, Jean Toomer, Anne Bradstreet, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Wallace Stevens, Robert Pinsky, Marianne Moore, and this being a stolidly American poem, our grandparents Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson.

Contemporary poets who’ve tried their hand include John Ashbery, who weaved together Gerard Manley Hopkins, Lord Byron, and Elliot; as well as Peter Gizzi who in “Ode: Salute to the New York School” made a cento from poets like Frank O’Hara, James Schuyler, and Ashbery. Lehman has tried his own hand at the form, to great success. In commemoration of his Oxford Book of American Poetry, he wrote a cento for The New York Times that’s a fabulous chimera whose anatomy is drawn from a diversity that is indicative of the sweep and complexity of four centuries of verse, including among others Robert Frost, Hart Crane, W.H. Auden, Gertrude Stein, Elizabeth Bishop, Edward Taylor, Jean Toomer, Anne Bradstreet, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Wallace Stevens, Robert Pinsky, Marianne Moore, and this being a stolidly American poem, our grandparents Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson.

Lehman contributed an ingenious cento sonnet in The New Yorker assembled from various Romantic and modernist poets, his final stanza reading “And whom I love, I love indeed,/And all I loved, I loved alone,/Ignorant and wanton as the dawn,” the lines so beautifully and seamlessly flowing into one another that you’d never notice that they’re respectively from Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Edgar Allan Poe, and William Butler Yeats. Equally moving was a cento written by editors at the Academy of American Poets, which in its entirety reads:

In the Kingdom of the Past, the Brown-Eyed Man is King

Brute. Spy. I trusted you. Now you reel & brawl.

After great pain, a formal feeling comes–

A vulturous boredom pinned me in this tree

Day after day, I become of less use to myself,

The hours after you are gone are so leaden.

Take this rather remarkable little poem on its own accord. Its ambiguity is remarkable, and the lyric is all the more powerful for it. To whom is the narrator speaking, who has been trusted and apparently violated that loyalty? Note how the implied narrative of the poem breaks after the dash that end-stops the third line. In the first part of the poem, we have declarations of betrayal, somebody is impugned as “Brute. Spy.” But from that betrayal, that “great pain,” there is some sort of transformation of feeling; neither acceptance nor forgiveness, but almost a tacit defeat, the “vulturous boredom.” The narrator psychologically, possibly physically, withers. They become less present to themselves, “of less use to myself.” And yet there is something to be said for the complexity of emotions we often have towards people, for though it seems that this poem expresses the heartbreak of betrayal, the absence of its subject is still that which affects the narrators so that the “hours…are so leaden.” Does the meaning of the poem change when I tell you that it was stitched together by those editors, drawn from a diversity of different poets in different countries living at different times? That the “true” authors are Charles Wright, Marie Ponsot, Dickinson, Sylvia Plath, and Samuel Beckett?

Steiner claims that “There is, stricto sensu, no finished poem. The poem made available to us contains preliminary versions of itself. Drafts [and] cancelled versions.” I’d go further than Steiner even, and state that there is no individual poet. Just as all drafts are ultimately abandoned rather than completed, so is the task of completion ever deferred to subsequent generations. All poems, all writing, and all language for that matter, are related to something else written or said by someone else at some point in time, a great chain of being going back to the beginnings immemorial. We are, in the most profound sense, always finishing each other’s’ sentences. Far from something to despair at, this truth is something that binds us together in an untearable patchwork garment, where our lines and words have been loaned from somewhere else, given with the solemn promise that we must pay it forward. We’re all just lines in a conversation that began long ago, and thankfully shall never end. If you listen carefully, even if it requires a bit of decipherment or decoding, you’ll discover the answer to any query you may have. Since all literature is a conversation, all poems are centos. And all poems are prophecies whose meanings have yet to be interpreted.

Image credit: Unsplash/Alexandra.