1.

In 1984, George Orwell’s year of looming dystopia, I received an academic scholarship to study fine arts and moved to Germany, a country that had embodied modern dystopia to an unprecedented degree. The scholarship, awarded to students of the United States and the United Kingdom, had been created in commemoration of the Berlin Air Lift of 1948–1949. It carried the cumbrous name “Luftbrückendank” (literally “Air Lift Thanks”), which amused my artist colleagues but reminded them that the Allied forces occupying their country still retained a degree of legal jurisdiction over the whole of East and West Germany—inducing in them that strange mixture of irritation, envy, and respect that anything American inspired in Europe at the time.

You lose several important parts of yourself when you move to another country. First you lose your language: struggling to explain things in simple terms, grappling with a new grammar and syntax, you wince at the wince on the face of the person you’re talking to as you stumble through your botched sentence. The next thing you lose is your identity as a citizen, as a member of an ethnic group, as a native. Eventually, however—and this is the strange part—loss leads to gain. You learn to master this new language, grow comfortable in this new culture: You crack jokes, slip into slang; it becomes second nature, and you think in it now, dream in it.

This loss and gain does not, of course, revert to a default setting when I’m back home; it’s permanent, and it colors my perception of America. I am both of us and not of us. I’ve begun the process of acquiring dual citizenship, of declaring not only an emotional but also a formal loyalty to my adopted home—but although I pay my taxes there, am raising my child there, have lived considerably more than half my life there—my position is and always will be ambivalent. Because I didn’t stay to absorb the changes gradually, adapt to them organically, the current state of affairs—our own new 1984—comes as a profound shock.

2.

Leave America, and you begin to see it as the rest of the world sees it: as an unpredictable, potentially hostile force dedicated exclusively to protecting its own interests; as a gargantuan military power with an aggressive presence on the world stage and a dangerously undereducated populace. We’ve toppled governments, covertly assassinated democratically elected leaders, waged illegal wars that have poisoned and destabilized entire regions around the globe. The enormous postwar bonus we’ve enjoyed—our status as the world’s darlings—has been eroding steadily away, yet incredibly, we still imagine that everyone loves us. Peering wide-eyed from our self-absorbed bubble, we issue Facebook “apologies” to the rest of the world for our mortifying president and his absurd coterie, not quite realizing that the world, at this point, is less interested in how Americans feel than in foreseeing, assessing, and coping with the damage the United States is likely to wreak on world peace, stability, economic justice, and the environment.

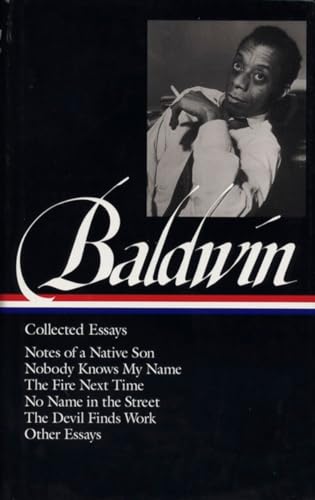

James Baldwin, after having spent more than a decade in France, observed that “Europeans refer to Americans as children in the same way that American Negroes refer to them as children, and for the same reason: they mean that Americans…have no key to the experience of others. Our current relations with the world forcibly suggest that there is more than a little truth to this.” Although Baldwin was conflicted by the feeling that he’d shirked his responsibility by moving abroad, and he returned many times throughout the civil rights era, he also understood that a great deal of his artistic and intellectual maturity had grown out of the distance he’d put between himself and his native country.

A special type of perception arises when we see something we already know fairly well but after a protracted absence: when it’s stripped of its familiarity and all of a sudden becomes a strange new thing—but only for a little while. Habit quickly settles back in and the specialness of this particular type of perception fades. For the first few moments, though, you get a sense that what you’re seeing is essentially reality, divested of its numbing effect. It’s kind of like the mildly hallucinatory state one experiences on psilocybin, and I get an initial jolt of this kind every time I come back to the U.S. It starts in the airport: For a minute or two, the entire scene, including myself standing in a line of passengers waiting to proceed through passport control, feels like an insane asylum in which utter nonsense issues forth from TV screens everywhere while people barely take notice or, worse, watch with interest and don’t find it shocking at all. The fake jokiness of the news, the non-news content of it, the stupefaction, the graphics. The entire appalling reality of what the country has become and the memory that it used to be very different.

When a German friend of mine visited me one year in Brooklyn, she remarked that she felt confused: Everything looked and sounded just as it did in the movies and on TV—the cops-and-robbers-blare of the police sirens, the steam rising in thick clouds from the manhole covers—it was all too familiar; she’d seen it all hundreds of times, and therefore nothing seemed real. While I found myself struggling to articulate this indescribable thing—the surreal whatness of things, the sense that everything had fallen under some kind of evil spell—to her, American identity, or Americanness, felt like a simulation of itself. This narrative insistence, narrative hegemony even, this adamant and endless proclamation of ourselves, is virtually unique to the United States in its power and its exclusion of the rest of the world. It not only permeates every facet of life in the U.S. but also implicitly questions the validity of other cultural identities it has not, in some way, already absorbed. Indeed, other narratives are virtually untranslatable unless they conform to the American script and contain the requisite ingredients. You need a good guy and a bad guy; you need a dream and something standing in the way of that dream. You need inauspicious circumstances that threaten to defeat the hero so that he can take heart, rise to the challenge, and win.

The national narrative is a narrative of infantilization, a fairy tale written for children in which love, sex, family, in fact all human endeavor, is sentimentalized, stripped of nuance and ambiguity and all of life’s inherent contradictions. We need everything spelled out; we are a culture with childish notions, even of childhood. It’s as though the American mind were calibrated to a single overriding narrative: It can be found not only in our movies but in our politics, our journalism, our school curricula; it’s on our baseball fields, in our TED talks, award ceremonies, and courts of law, among our NGOs and in our cartoons and the way we speak about disease and death—virtually anywhere we enact the stories we’ve created about our history; our collective aspirations; our idea of who we are and what we’d like to become. But to disagree with this narrative, to call its major premises into question, is to betray the tribe.

Identity is a construct that forms in response to a psychic need: for protection, for validation, for a sense of belonging in a bewildering world. It’s a narrative; it tells itself stories about itself. But identity is also a reflex, a tribal chant performed collectively to ward off danger, the Other, and even the inevitable. Its rules are simple: They demand allegiance; they require belief in one’s own basic goodness and rightness. It’s a construct based not in fact but on belief, and as such it has far more in common with religion than with reason. I try for the life of me to understand what it is and how the fiction of what this country has become has turned into such a mind-altering force that one can only speak of mass hypnosis or a form of collective psychosis in which the USA still, bafflingly, sees itself as the “greatest nation on Earth,” in which anything that calls what makes America American into question is met not with impartial analysis or self-scrutiny but indignant and often hostile repudiation. We have, as Baldwin observed in his Collected Essays, “a very curious sense of reality—or, rather…a striking addiction to irreality.” Are we really as brave as we think we are; are we as honest, as enterprising, as free as we think we are? We’re not the envy of the world and haven’t been for a long time, and while this might not match the image we have of ourselves, it’s time to address the cognitive dissonance and look within.

Identity is a construct that forms in response to a psychic need: for protection, for validation, for a sense of belonging in a bewildering world. It’s a narrative; it tells itself stories about itself. But identity is also a reflex, a tribal chant performed collectively to ward off danger, the Other, and even the inevitable. Its rules are simple: They demand allegiance; they require belief in one’s own basic goodness and rightness. It’s a construct based not in fact but on belief, and as such it has far more in common with religion than with reason. I try for the life of me to understand what it is and how the fiction of what this country has become has turned into such a mind-altering force that one can only speak of mass hypnosis or a form of collective psychosis in which the USA still, bafflingly, sees itself as the “greatest nation on Earth,” in which anything that calls what makes America American into question is met not with impartial analysis or self-scrutiny but indignant and often hostile repudiation. We have, as Baldwin observed in his Collected Essays, “a very curious sense of reality—or, rather…a striking addiction to irreality.” Are we really as brave as we think we are; are we as honest, as enterprising, as free as we think we are? We’re not the envy of the world and haven’t been for a long time, and while this might not match the image we have of ourselves, it’s time to address the cognitive dissonance and look within.

Before the fall of the Berlin Wall, German identity was predicated on the rejection of the Other. And because the two Germanys defined themselves in opposition to one another, because each of them claimed a moral superiority over the other, one that was contingent on the depravity of the other—that blamed the fascist past on the other—anything that touched upon this taboo was a threat.

The ’90s were an intense time to be in Berlin, and it took a foreigner, the French artist Sophie Calle, to see and address what almost every German I knew wasn’t able to: the fact that the country was slipping, post-Reunification, into a state of selective amnesia. Her work Detachment (1996), in which she asked passersby to describe emblems of German Democratic Republic history that had been removed—including the gigantic wreath with hammer and sickle on the Palast der Republik, the former East German parliamentary building that would itself soon be demolished—succinctly captures an era of collective repression during which the past was in a process of being rewritten. The empty space left behind by the removed monument or plaque became a gap in memory that could not be filled by the largely inaccurate descriptions of passersby, no matter how emotionally charged or how close to home. Eventually, as an entire country struggled with the transition from planned economy to free-market capitalism and it slowly dawned on the former citizens of the GDR that the West was not the utopia they’d imagined it to be, this gap would be filled by “Ostalgie,” a nostalgia for all things East—matched in intensity only by the witch hunts carried out on anyone with even the most tenuous Stasi connection in their past. But then again, idealization and demonization have always gone hand in hand, while maintaining power depends on controlling the narrative and interpreting the evidence.

The ’90s were an intense time to be in Berlin, and it took a foreigner, the French artist Sophie Calle, to see and address what almost every German I knew wasn’t able to: the fact that the country was slipping, post-Reunification, into a state of selective amnesia. Her work Detachment (1996), in which she asked passersby to describe emblems of German Democratic Republic history that had been removed—including the gigantic wreath with hammer and sickle on the Palast der Republik, the former East German parliamentary building that would itself soon be demolished—succinctly captures an era of collective repression during which the past was in a process of being rewritten. The empty space left behind by the removed monument or plaque became a gap in memory that could not be filled by the largely inaccurate descriptions of passersby, no matter how emotionally charged or how close to home. Eventually, as an entire country struggled with the transition from planned economy to free-market capitalism and it slowly dawned on the former citizens of the GDR that the West was not the utopia they’d imagined it to be, this gap would be filled by “Ostalgie,” a nostalgia for all things East—matched in intensity only by the witch hunts carried out on anyone with even the most tenuous Stasi connection in their past. But then again, idealization and demonization have always gone hand in hand, while maintaining power depends on controlling the narrative and interpreting the evidence.

3.

A few days ago, I took my son to see the Andres Veiel film on Joseph Beuys, which premiered at the Berlinale earlier this year. I hadn’t actually thought about Beuys in a long time, but it seemed to make sense to turn my 16-year-old budding graffiti artist on to some bona fide radicalism in art. The first time I saw Beuys’s work was in the 1979 show at the Guggenheim, and I understood nearly nothing. Gradually, of course, I came to see the ways in which Beuys—both his person and work—epitomized the psychological drama of postwar West Germany, but what I’ve rediscovered now, after seeing the Veiel film, is that he also had quite a lot to say about America—and that he and his art are as relevant today as they were 40 years ago.

In May of 1974, Beuys, wrapped in felt from the moment his plane touched ground on the American continent, was taken to the Rene Block Gallery in Soho in an ambulance. The plan was to spend several days locked up in a room with a coyote. I Like America and America Likes Me was Beuys’s cryptic and poetic critique of the country and its violent history; in choosing an animal indigenous to the North American continent for over a million years, an animal that is totemic in Native-American mythology and that inspired the coyote deity stories dating back over 10,000 years, the oldest known literature on the continent—an animal that nonetheless fell victim to a bitter, widespread, and ruthless extermination campaign—Beuys instinctively went for America’s Achilles heel: its founding genocide. His action took on the guise of a shamanistic ritual: America was spiritually ill, he contended, the result of a violent psychological repression; there was “a score to be settled with the coyote,” Beuys said, “and only then will this trauma be over.”

“We know,” Baldwin wrote, “that whoever cannot tell himself the truth about his past is trapped in it, is immobilized in the prison of his undiscovered self. This is also true of nations.” When you consider that Germany has been confronting the worst elements of human nature for over 70 years—that its history and its own obsessive and enduring examination of this history have left little in the way of pride—it becomes clear what happens when a national narrative is rewritten through an experience of profound shame. It’s a lesson in humility, one we’d all be well-advised to learn. We’re talking relentless national debate, relentless historical analysis. Picture three full pages of The New York Times dedicated every day, over a period of decades, to uncovering layer upon layer of past atrocities; picture a debate, continuing over decades, over the myriad ways in which history nonetheless continues to collude. Picture the U.S. getting anywhere near this thorough a look at its own history: the true circumstances surrounding Europe’s arrival in the Americas, for instance, or the ruthless exploitation and eventual extermination of the indigenous population and the never-ending legacy of slavery. Imagine the U.S. making this historical analysis a mandatory part of its school curriculum, nationwide. In Germany, pride has been taken in an absence of the very pride that led it to the abyss in the first place, in an aversion to grandiosity and hyperbole and fanaticism, in a distance to and general suspicion of national identity. Now, however, and in spite of all it’s learned, the country is faced with the emergence of a radical right that, for the first time in 60 years, has garnered enough votes to enter the German national parliament—a startling fact that demonstrates the precariousness of any social equilibrium in the face of rabid populist revisionism, no matter how long or bitter the struggle to achieve it.

4.

4.

There’s the old story of the frog sitting in a pot of water on the stove: As the temperature rises, the change is too gradual for the frog to detect the danger and escape to safety. National culture exerts a similar spellbinding effect, in which all forces serve to craft and reinforce a narrative that passes for objective reality. One of nationalism’s most deleterious illusions is that “evil” is something that comes from without—and not something lurking inside each of us, waiting to be activated, waiting to be unleashed. In the words of Baldwin, writing about Shakespeare, “all artists know that evil comes into the world by means of some vast, inexplicable and probably ineradicable human fault.” Taking this thought to its logical conclusion, Einstein claimed in Ideas and Opinions, “in two weeks the sheeplike masses of any country can be worked up by the newspapers into such a state of excited fury that men are prepared to put on uniforms and kill and be killed, for the sake of the sordid ends of a few interested parties.” We are, in other words—despite our prodigious brains—still very much animals, subject to a herd mentality. But there is also a subtler form of spellbinding, one that lies in acquiescence. Americans know they’re in crisis, understand that their democracy is at risk, yet what I see—with very few exceptions beyond the occasional comparisons to the Weimar era that directly preceded the advent of fascism in Germany—are not efforts to transcend national identity in order to understand the dangerous ways in which the human mind is vulnerable to suggestion and manipulation, but a clambering to recover American “values” and cherished attributes and to reaffirm them.

One of the arenas in which these efforts are enacted is language itself. Yet while Orwell foresaw the rewriting of the historical past and the falsification of existing documents, including newspaper archives, books, films, photographs, etc., to bring them into line with party doctrine and prove its infallibility—while he predicted the reduction of language as a powerful tool to curtail the radius of human thought for political ends and postulated a semantic system in which words are used to denote their opposite and are thus rendered meaningless—even the broadest political, historical, and psychological analysis of how propaganda has been used throughout the ages to whip up popular support and manipulate the mass mind pales when applied to the phenomenon of fake news, which takes “Newspeak” and multiplies it to kaleidoscopic dimensions.

All the U.S. needs is one good international crisis for the patriotism reflex to kick in: It’s an immediate emotional response, yet what is needed most in times of shock is a suspension of emotion, distance to the forces that would manipulate us. What happens is this: Something shakes us to the marrow, we rally around what makes us feel safe—and it’s the bulwark of national identity we cling to, even if this identity is precisely what clouds our cognitive faculties most. But when someone steps forward and offers a truly critical perspective—Susan Sontag in the days immediately following 9/11 comes to mind here—this is the moment she is held in the greatest suspicion, because critical distance means that she is not part of the emotional bond a reaction to a state of shock brings about, that the observations she makes or the conclusions she draws might find fault not with some evildoing Other but with us, with our own. Better to brand the critic an alien with alien allegiances—in other words, something dangerous: a tainting, a contamination, a contagion.

It’s through narrative that reality acquires meaning and becomes intelligible, that it conceives itself, enacts itself. Yet the national narrative has made it virtually impossible for Americans to perceive themselves and the world around them in any accurate or objective way. Words have morphed to the point where they no longer signify anything but rather act as invisible triggers, actively shut thought down and preclude the possibility of communication. Everywhere we look, we see what we want to believe about ourselves. We are, after all, the birthplace of Hollywood: It should come as no surprise, then, that we prefer fairy tales to the laws of nature and the tedious facts of reality; that the boundaries between fact and fiction have not only blurred but have become, to us, undetectable. “We are often condemned as materialists,” Baldwin wrote. “In fact, we are much closer to being metaphysical because nobody has ever expected from things the miracles that we expect.” We’re in the business of inventing superheroes with fabulous, gravity-defying superpowers and have been daydreaming about them for such a long time that it’s entered our collective subconscious, become a part of our DNA. And so we imagine that Robert Mueller and his investigation will save us, or Stormy Daniels and her titillating revelations, or our very own Jeanne d’Arc, Emma Gonzalez, with the incorruptibility of youth and a God-given ability to speak truth to power.

As written in the German paper Die Zeit, the “ostentatious vulgarity” of the present American administration “shouldn’t distract us from the fact that…something is happening that goes beyond mere audacity, that cannot really be described, even with the word ‘propaganda,’ a term that today has become inflated and imprecise.…It’s more about doing away with the principle of truth altogether, the categorical differentiation between true and false.” As the author of the article mentions, the philosopher Hannah Arendt analyzed precisely this in an interview with Roger Errera in 1974: “If people are constantly lied to, the result isn’t that they believe the lies, but rather that no one believes anything at all anymore.…And a people that can no longer believe anything cannot make up its mind. It is deprived not only of its capacity to act but also of its capacity to think and to judge. And with such a people you can then do what you please.”

As far as Germany is concerned, it’s not entirely clear whether the lessons learned and the insights gained during the long and painful process of Vergangenheitsbewältigung (a term referring to Germany’s process of coming to terms with its Nazi past) will be lasting ones; if they can immunize the country against the dangers of recurrence. The rapidly growing popularity of PEGIDA (Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamicization of the Occident) and the AfD (Alternative for Germany) and their reactionary anti-immigration and anti-Europe agendas remind us how precarious and contingent the current state of affairs remains, how enduring the fear of the Other continues to be. Yet it’s only when a populace ventures beyond the spellbinding effects of its collective identity—when the national debate succeeds in illuminating the blind spots of this identity to compare one culture’s hallucinations with another’s—that it has a chance at breaking that spell. What unites us most is how quickly our efforts can be instrumentalized for someone else’s purposes—and the ease with which we can be duped and played. We aren’t living in Orwell’s world, yet—we still have time to reclaim some of what’s been lost—but it’s anyone’s guess how much time remains.

Image: Flickr/Darron Birgenheier