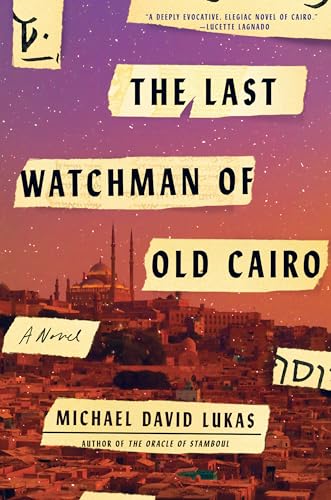

A few years ago, Michael David Lukas wrote about what he calls the “polyphonic novel” for this site. His new novel is a jewel of the form, weaving voices of modern Cairo with those from the city’s millennium-plus history, and describing events leading to the discovery of the famed Genizah trove in the Ben Ezra Synagogue. Lukas is interested in the sites of Jewish history in Muslim-majority contexts–his first novel, The Oracle of Stamboul, was a magical realist work about a Jewish girl during the waning days of the Ottoman empire. The Last Watchman of Old Cairo juxtaposes the peregrinations of Joseph–a young American graduate student with Egyptian Muslim and Jewish roots–with the life of a distant forbear and those of the so-called “Sisters of Sinai,” who played a critical role in the development of scriptural history. In addition to his novel-writing, Lukas works at the Center for Middle Eastern Studies at UC Berkeley (where I also used to work, although we didn’t overlap–we met on a losing team at a book trivia fundraiser thing, and now meet up every so often to discuss books and babies). At Berkeley, he runs an online exchange between students in the U.S. and the Middle East. I spoke with him about how this novel, like that work, looks for the sites of coexistence in a long shared past.

The Millions (TM): Tell me about the Genizah and the source material for the book.

Michael David Lukas (MDL): So, I’ll start with the first seed, which was that I studied abroad in Cairo during my junior year of college. It was a weird period in my life, and in the world, and it was my first time living in the Arab World. I was feeling somewhat alienated from my Jewishness. It was during the Second Intifada–I was hyper aware of, and also very conscious of, and also sort of defensive about, and alienated from my Jewishness all at the same time. I was really enjoying the city but having a hard time figuring out how I fit into it. And in the midst of this, I came upon the synagogue at the heart of the city. Seeing that, and realizing that there was thousand-year-old history of Jews in Cairo, I had a sense not only of the possibilities of coexistence, but also of how I fit into the place.

And then later on, I learned that this synagogue is the site of all these amazing stories and of the famed Genizah in its attic. Jews would hold onto any piece of paper that had the word “God” written on it; there was a prohibition against throwing away those pieces of paper. So for hundreds and hundreds of years, they kept these pieces of paper up in the attic because it was dry. They didn’t mold, and in the 19th century they were discovered by Solomon Schechter and the British twins, Agnes Smith Lewis and Margaret Dunlop Gibson.

That’s the first seed, and it was dormant for a long time. Then many years later I had an experience where I sat next to this woman on a plane and we ended up talking for basically the whole flight across the country, and she told me that her family had been the watchmen of a synagogue in Kolkata. She was Bengali Muslim. That sparked this memory of that other synagogue in Cairo and the Jewish-Muslim coexistence, and it all kind of came together.

TM: What sort of sources did you use to familiarize yourself with the twins, and with their part of the story?

MDL: They were so interesting. They were very Victorian, bible-hunter-type folks, but also very quirky. Luckily there are a few books written about them. One in particular called The Sisters of Sinai was useful. They actually wrote a couple of books about their experiences as well, so I knew their voices, and I knew how I wanted to position them in the narrative–kind of this driving force behind the discovery that didn’t really get recognized as a driving force at the time.

MDL: They were so interesting. They were very Victorian, bible-hunter-type folks, but also very quirky. Luckily there are a few books written about them. One in particular called The Sisters of Sinai was useful. They actually wrote a couple of books about their experiences as well, so I knew their voices, and I knew how I wanted to position them in the narrative–kind of this driving force behind the discovery that didn’t really get recognized as a driving force at the time.

One thing that was difficult about it was that as much as they were proto-feminists, and really remarkable for what they were able to accomplish at a time that was quite misogynist and when women weren’t able to go to Cambridge, they were also, as one would imagine, pretty imperialistic. So I didn’t want to lionize them even though they are in one sense heroes of the story. Since it was such a close point of view, it was hard to figure out ways to show their colonialist mentality, without reifying it, or supporting it. I ended up having them be proven wrong in a number of ways about their assumptions about Egyptians, or about the way things work in Egypt, when these assumptions were undercut by events.

TM: Your last novel also had a Jewish protagonist in a Muslim-majority context,.

MDL: My brother-in-law was like, “You gotta stop writing these Jewish novels, no one cares.”

TM: Your novel-in-progress is also a Jewish novel, right?

MDL: My current novel is different because it’s set in the future. You don’t necessarily realize that it’s a Jewish protagonist, although it’s a rewriting of the Book of Esther. It’s more like The Lion, The Witch, and The Wardrobe is a Christian novel. I think to a Jewish reader it feels very Jewish, but I think to other readers it might not.

MDL: My current novel is different because it’s set in the future. You don’t necessarily realize that it’s a Jewish protagonist, although it’s a rewriting of the Book of Esther. It’s more like The Lion, The Witch, and The Wardrobe is a Christian novel. I think to a Jewish reader it feels very Jewish, but I think to other readers it might not.

TM: It’s an Abrahamic novel.

MDL: Exactly, Abrahamic. That was really the whole point. That’s the idea behind the original title, which was the 43rd Name of God. The idea being, there are lots of names for God, to encapsulate one entity or one way of being.

TM: I love how The Last Watchman highlights the fact that Jewish history–and Arab history, and Muslim history–is so rich and complex as a result of the interplay of cultural and religious traditions. When you talk to Jewish people and tell them you’re writing about Jews in a Muslim-majority context, what kind of responses do you get?

MDL: I think about it this way: Jews have been in the United States for 350 years. Jews were in Cairo for a thousand. Within that kind of time span, you have ups and downs, obviously. But that long history of Jews in the Arab world has been erased in a lot of ways, for political means, or political purposes, by all parties.

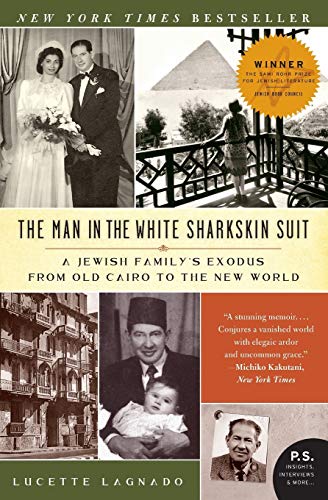

I’m very careful to paint neither too rosy a picture, nor too much of a picture of conflict. I chose the time period of the novel specifically to be able to paint a picture that was complex. The two books that I can think of about Cairene or Egyptian Jews are Lucette Lagnado, The Man in the White Sharkskin Suit, and André Aciman’s Out of Egypt. Those are both personal memoirs about the expulsion of the 1950s, when Gamal Abdel Nasser expelled foreigners from Egypt and put Jews in that category. Some Jews were foreigners, from Italy, France, or what have you, but there were other Jews who were from Cairo, whose families had lived there for a thousand years.

I’m very careful to paint neither too rosy a picture, nor too much of a picture of conflict. I chose the time period of the novel specifically to be able to paint a picture that was complex. The two books that I can think of about Cairene or Egyptian Jews are Lucette Lagnado, The Man in the White Sharkskin Suit, and André Aciman’s Out of Egypt. Those are both personal memoirs about the expulsion of the 1950s, when Gamal Abdel Nasser expelled foreigners from Egypt and put Jews in that category. Some Jews were foreigners, from Italy, France, or what have you, but there were other Jews who were from Cairo, whose families had lived there for a thousand years.

In terms of the response I get, generally people are pretty interested. There’s a kind of wide appetite for this sort of thing, if only because it stakes a Jewish claim in this place. Then there are a lot of Jews who are very focused on the late twentieth-century conflict, and that history. So they aren’t really trying to hear the previous history, which doesn’t fit into the narratives of “it was really bad and then Israel came along and they were saved,” which sort of reverses the chain of events as they actually happened.

Generally, people are pretty happy to read about Jewish lives. The book is so much about this interplay between Muslim and Jewish identity, I’ll be curious to how people react to that.

TM: What is the Cairene Jewish community like today?

MDL: There aren’t that many Jews who still live in Cairo. When I was there in the year 2000, I went to Rosh Hashanah services and the synagogue was completely full, but it was mostly staffers from the American and Israeli embassies, and oil company employees. There were a few Cairene Jews who were there, and I based some characters in the book on them, like sort of seeing them from a distance.

But apparently there’s been a real resurgence in interest in Jewish history in Egypt. There was a little mini-series on TV and there have been a few people who have rediscovered their Jewish roots, including one famous actor who came out as Jewish, with a Jewish mother. There were a couple of famous Jewish actors during the golden age of Egyptian cinema, one of whom converted to Islam in order to advance her career. Which sounds crazy, but it happened in Hollywood all the time.

Jews were a part of the cultural fabric. You can see these little traces of that history if you know what to look for, but you really have to know what to look for.

TM: You were an undergraduate when you were in Cairo the first time. Did you go back and do more research for this book?

MDL: Well I set it in the year 2000, which is when I was still there, which is sort of a cop-out. I went back a couple times subsequently, just to get a sense of the place and the feeling of being there. Being in Cairo is such a visceral experience, the sweaty taxi seat sticking to your back–that’s basically what I went back for, to reacquaint myself with what it’s like to be in the city.

TM: Why do you say cop-out?

MDL: I wanted the book to take place before the Arab Spring, because that’s the city I’m familiar with. When the Arab Spring was happening, I was two or three years into writing the book, and every person I would talk to about the book would say something like “Oh, that’s so relevant. You’re going to work in some Arab Spring angle.” And I really didn’t want to do that. In part because it was happening as we were talking, and in part because I knew I wouldn’t do it justice.

TM: Well it seems that few people who tried to sound authoritative about it at the time did it justice.

MDL: Yes, looking now–where the security apparatus is deeply paranoid, even more so than it was, even more authoritarian and regressive than it was.

TM: I think the angle of your story is so specific, and it’s looking at a kind of interaction and historical mosaic that is not usually emphasized in discussions about the so-called “Middle East” in the United States. But you’re still an American writing about Egypt in a weird American moment. Did you feel anxious about how to fairly depict Egyptians?

MDL: I definitely thought about it a lot. The answer that I came to is that it’s sort of a story that would be difficult to be told by anybody, because there are so many different perspectives and identities at play. That was sort of the point, was to create a mosaic of different perspectives. There’s the Presbyterian Scottish twin. There’s the half-Muslim, half-Jewish graduate student. There’s the Muslim teenager in the 11th century. In writing a polyphonic novel, you force yourself into writing perspectives that aren’t your own.

TM: And your graduate student protagonist is also a gay man.

MDL: That was something I definitely thought about. As with all of these characters, his identity was fully formed when I met him, so it’s really not an issue of deciding, is he going to be gay or not? It was about deciding how to represent that and deal with who he was, protagonist-wise.

TM: When you say, when you met him, he just shows up in your brain?

MDL: Yeah. Joseph just kind of showed up as who he was. The thing that was hardest was not trying to write a half-Muslim, half-Jewish character, or a gay character, although I thought a lot about those things and talked to a lot of friends as I was doing it. The thing that was most difficult is that he’s the character who felt closest to me, closer than any person I’ve ever written, and I really identified with him. I got, I think, overly identified with him, and was trying to write him as me, as a sort of version of myself. At a certain point I realized I needed to take a step back from him. He was his own person, a fictional person and I needed to write him as who he was–someone who had a lot of the same experiences as me, but also separate.

TM: I’m laughing because that’s exactly the way you could talk about having a child. You just meet them and that’s just what they’re like–you can’t change anything fundamental about them so much as steer, or course-correct. You forget and try to make them you (a better you, obviously), but they’re not you.

MDL: It’s exactly like that. It’s like trying to be the best parent that you can be to that particular child, and wondering who they are, rather than trying to impose who you are on them. While also recognizing that they’re a piece of you.

I do think having a child made me better understand my own writing in general. I think for Joseph I didn’t fully get him until I was able to see him as a child, from his parents’ perspective, and to see the brat that he was, in a way. Seeing that I was like, oh, now I get it. Because it’s a novel about his relationship to his parents in a lot of ways. I was missing that huge piece and didn’t know I was missing it.