As I think is the case for most writers born after 1980, the first outlets to publish my work were online. To be more specific, they were blogs—online spaces that valued ideas and abstraction over narrative and detail. My writing followed an outline similar to the five-paragraph essay: here’s what I’m trying to communicate, here’s how it affects you, here’s how you should respond.

I am grateful for these online outlets: they gave me deadlines and creative autonomy and a reason to write outside of the college classroom where I took my first creative writing courses or, later, my nine-to-five office job. But writing for the Internet did not teach me about concreteness or precision. It taught me to come up with an argument and explicate, maybe with a brief anecdote to catch the reader’s interest. The actual substance of the material world rarely made an appearance.

I learned about particularity from literature. Books reward attention to detail by virtue of being physical objects. You can flip to the end of a novel if you like, but it feels like cheating—much more than skimming an online article, index finger flicking across the mouse. Books aren’t designed to seize the reader with wild titles or to funnel her through a story using lists and bite-sized sections. They are designed to construct worlds furnished with smells and objects and memories, and this construction requires the accumulation of concrete and specific building blocks.

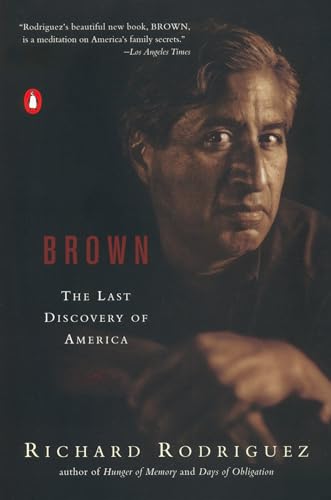

In Brown: the Last Discovery of America Richard Rodriguez writes, “Literature flows to the particular, the mundane, the greasiness of paper, the taste of warm beer, the smell of onion or quince…Literature cannot by this impulse betray the grandeur of its subject—there is only one subject: What it feels like to be alive. Nothing is irrelevant. Nothing is typical.”

Durga Chew-Bose’s first essay collection, Too Much and Not the Mood, is a ranging, intricate work crowded with lush detail. Her prose blends commentary on pop culture with the precision of literature. It flows to the particular, just as Rodriguez suggests literature should. Nothing is irrelevant: not the examination of an emoji, not Allen Iverson’s voice, not a “lathery shade of peach” in a painting at the Met. Chew-Bose is meticulous in recording what it feels like to be alive, down to the most unassuming observations: “A poorly painted wall. Its cracks. The ceiling fan’s chop. A woman on the C train pulling her ponytail through its tie, not once or twice, but six times.”

Not only does Chew-Bose welcome life’s minutiae into her writing, she delights in it, a fact that lends even her densest and most tangential prose charm. No object or observation is too mundane to elicit wonder. Under her attention, there’s awe to be drawn from a scene in The Godfather or the emotional power of cheap pop songs, the kind with “nowhere lyrics that repeat one word over and over like a hymn written in neon-tube lighting.” That is, songs that send us singing down the freeway, gleefully unabashed and willing to roll the windows down even in a drizzle. (Or maybe that’s just me.)

Too Much and Not the Mood celebrates the minute experiences that heighten our capacity for wonder. The book reminded me that an event, a trip, or a day is the sum of its concrete parts, a compilation of every miniature, material detail: the bricks that form a home. Under Chew-Bose’s keen-eyed observation, a wedding is not a wedding in the abstract sense of the word; it is the glimpse of gold sandals under a dress, a chilled red wine, “sequined strings of twinkle lights blurring with purple bougainvillea vines,” desert mountains turning jewel tones, and cake abandoned on plates while guests dance.

I read Too Much and Not the Mood in my final residency of graduate school. I was leaving behind two years of immersion in language, and my preemptive nostalgia meant paying closer attention than usual to my surroundings and sensations: the spike of sage in the air, the rock-salt rim of a margarita, a poem recited aloud as trees waved in agreement outside the window. I read Chew-Bose’s essays at a courtyard table in Santa Fe as thunderstorms rolled in and out and rain speckled the book cover and my cohort and I reached across one other for snacks and hummed over words.

That’s what her writing did for me: it made me hum in recognition. Even though her particulars are not mine, she reports them with an accuracy that generates recognition. They are specific enough to jolt my own memories. When she writes that she is happiest “barefoot in [my parents’] home eating sliced fruit,” I felt my parents’ hardwood kitchen floor under my feet and tasted crescents of peach, placed one after another onto my tongue. That is the essence of childhood summers for me, and the essence of what I’ve left behind in becoming an adult: the backyard in Santa Barbara, a warm towel under my stomach as I lay in the grass reading a library book, cherries or a peach within reach.

I imagine Chew-Bose’s wonder ignites a similar emotion in most readers, if not through recognition than purely through the aesthetics of her language. Take this passage: “Palm trees pipe my sense of awe into its purest form. Puppies asleep on their sides, lattice piecrusts, and women in perfectly tailored pantsuits generate a similar response. So does young Al Pacino. …Those young Pacino eyes capsize me.” That specificity of example and those pitch-perfect verbs—pipe, capsize—supply plenty of wonder on their own.

Reading Too Much and Not the Mood reminded me I could write about these things—nostalgia for my parent’s kitchen, lattice piecrusts, cheap pop music—and not only that, but by honing in on the specifics of my own life, I could reach through the screen or the page and speak to the specifics of a stranger’s life. Chew-Bose’s zeroing-in on the miniature proves that experiencing beauty often requires paying close attention. Which is perhaps good advice for writing as much as for life. “Thinking of someone the way he was is really just another way of writing,” Chew-Bose asserts in the opening, sprawling essay “Heart Museum.” “Thinking about someone I was once in love with—how he’d peel an orange and hand me a slice or how is white T-shirt would peek out from under his gray sweatshirt. … Thinking about that crescent of white cotton is a version of writing.” Too Much and Not the Mood can be read as a manual for how to write: pay close attention, and write about what captures.

A number of the essays in Too Much and Not the Mood first appeared in online publications like The Hairpin. I’m thankful that Chew-Bose is one of many writers restoring particularity to the Internet’s prose, as well as delight. A phrase like “a dragon fruit’s Dalmatian-speckled insides” is a reprieve, pointing me back to the tactile, intricate world outside my book or screen. Chew-Bose’s talent is to hold up objects to the light so they refract, expanding beyond their material existence—the concrete speaking to abstract concepts of affection, nostalgia, loss, and wonder. There’s something mischievous about giving attention to these objects, if only because they’re so likely to go unnoticed. In her exactitude, Chew-Bose points out what many of us miss: the glints, the one-offs, the seconds that normally scurry past. Look there, her writing seems to say. There it is—pay attention.