In the type of surprise move many Nobel watchers have become accustomed to, the committee has awarded the 2014 Nobel Prize in Literature to French novelist Patrick Modiano, a writer with a deep body of work, but one who was not among the “favorites” discussed in the flurry of pre-announcement speculation.

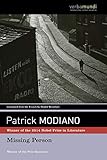

Modiano, 69, is best known for his Prix Goncourt-winning 1978 novel Missing Person. Publisher David R Godine calls it “a detective thriller, a 1950s film noir mix of smoky cafes, illegal passports, and insubstantial figures crossing bridges in the fog. On another level, it is also a haunting meditation on the nature of the self.” While Modiano’s novels have been published in English translations over the years, including by major publishers like Knopf, only a handful of his 25 or so books are currently in print in the U.S. These include Honeymoon and Catherine Certitude, a children’s book, illustrated by Sempe. Yale will be releasing a new edition next year that collects three Modiano novellas under the title Suspended Sentences. Update: Yale has announced that it will now publish the book in November 2014.

Modiano, 69, is best known for his Prix Goncourt-winning 1978 novel Missing Person. Publisher David R Godine calls it “a detective thriller, a 1950s film noir mix of smoky cafes, illegal passports, and insubstantial figures crossing bridges in the fog. On another level, it is also a haunting meditation on the nature of the self.” While Modiano’s novels have been published in English translations over the years, including by major publishers like Knopf, only a handful of his 25 or so books are currently in print in the U.S. These include Honeymoon and Catherine Certitude, a children’s book, illustrated by Sempe. Yale will be releasing a new edition next year that collects three Modiano novellas under the title Suspended Sentences. Update: Yale has announced that it will now publish the book in November 2014.

Here at The Millions, novelist J.P. Smith discussed reading Modiano in French:

All I knew of Modiano was that he wrote about his past and that of his parents, which was intricately bound up with the years of the German Occupation of France, a topic I was about to introduce into my own fiction. Modiano’s true subject, I discovered, is the nature of identity and memory as it’s distilled through the past—in itself a Proustian conceit—and what I find fascinating about him is that his many novels, which take up a good portion of a bookshelf, in a way are like individual chapters of one book. His theme is unchanging; his style, “la petite musique,” as the French say, is virtually the same from book to book. There is nothing “big” about his work, and readers have grown accustomed to considering each succeeding volume as an added chapter to an ongoing literary project. His twenty-five published novels rarely are longer than 200 pages, and in them his characters, who seem to drift, under different names, into first this novel, then another, wander the streets of Paris looking for a familiar place, a remembered face, some link to their elusive past, some ghost from a half-remembered encounter that might shed some light on one’s history. Phone numbers and addresses are dredged up from the past, only to bring more cryptic clues and, if not dead ends, then the kind of silence that hides a deeper and more painful truth.

You open the latest Modiano and you know exactly where you are. The writer is artistically all of a piece. It’s his obsession with memory and the haunted lives of his protagonists which truly caught my attention, and especially how he returns time and again to mine this subject. As someone with a very broken chronology, with a memory of childhood that is in many ways unreliable (how much has been planted there? How much of it is real? What’s been removed by doubt or by someone else’s will?), I saw in Modiano how the capriciousness of memory can in itself become the subject of a novel. And because back then I found plot a troublesome thing to handle in my fiction, the idea of creating a narrator in search of a story became the basis for my first novel. I sent Modiano a copy of it when it was published and, not surprisingly, heard nothing back.