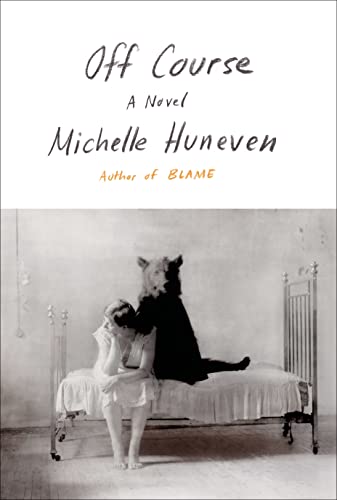

The epigraph of Michelle Huneven’s fourth novel, Off Course, reads like a warning:

If a woman in her late twenties hasn’t found an absorbing occupation, and if, restless or adventurous, she begins to drift, she flirts with peril; for this is a vulnerable age, when demons present, singly and in droves, often taking the forms of men.

When I read this, I immediately though of HBO’s Girls, and how it could easily serve as an epigraph for that show, as well. But as I made way through Off Course, my thinking changed. The most important part of the epigraph, I realized, was the very first phrase: “a woman in her late twenties”. The girls in Girls aren’t old enough to truly “flirt with peril”; they might get into trouble, but it’s unlikely that anything they do will throw their lives off course.

When I read this, I immediately though of HBO’s Girls, and how it could easily serve as an epigraph for that show, as well. But as I made way through Off Course, my thinking changed. The most important part of the epigraph, I realized, was the very first phrase: “a woman in her late twenties”. The girls in Girls aren’t old enough to truly “flirt with peril”; they might get into trouble, but it’s unlikely that anything they do will throw their lives off course.

The stakes are higher for a woman like Cressida Hartley, the heroine of Off Course. At 28, she’s a post-doc right on the precipice of adult life — or at least, a life out of school. All she has to do is write her dissertation. Her parents offer her the use of their summer cabin in the Sierras, a place she hated as a child. She accepts, thinking the isolation will be good for productivity. But she finds ways to procrastinate.

During her very first week, she hooks up with the local lothario and ends up dating him for months. It’s part of Cress’s charm, as well as her vulnerability, that she doesn’t care about his reputation. When their fling ends amicably, Cress gets down to work and, more importantly, you, the reader, begin to root for her. By then you understand what she’s up against: it’s not only that she has no interest in her dissertation (although this is a problem); it’s not only that she’s lonely (this is a bigger problem); it’s not only that she’s living in a house that is the embodiment of her childhood (an even bigger problem); it’s that the mountain itself exerts a pull on her. Her family’s cabin is a kind of Narnia for her, a place out of time visited by strange characters and surrounded by incredible natural beauty. On her very first night, Cress opens her window to feel the breeze, “bearing the scent of pine and mineral dust.” Above, “the moon cast a blue glow.” Already, we’re in the land of fairy tales (where demons might lurk) but Huneven caps off the passage with this ominous foreshadowing:

And so it was on familiar roads, in her family’s other home, with the blessings of those closest to her, that she veered off course, into the woods.

It’s hard to discuss how and why Cress veers off course without giving away too many details, but it doesn’t spoil much to reveal that a man is involved. I won’t say more about him except that he’s married, and his marriage throws up all the usual obstacles. It also puts you in the position of reading a romance from the point of view of “the other woman.” Although almost everyone in Cress’s life is judgmental of her choice, it’s hard to feel anything but sympathy for Cress. Still, she is a peculiar heroine. Or maybe she’s just adrift, and hard to pin down: She’s competent yet lost, independent yet passive, intelligent yet guileless. I found myself admiring her on one page and worrying about her on the next. Cress worries, too, at one point observing that she has begun to live “an offhand life,” one that she can’t look at directly, “for fear it would dissolve.”

Part of this novel’s power is that it spans several years, but time passes in a way that mimics life experience. The novel’s early chapters are warm and expansive and descriptive as Cress settles into her new mountain home and becomes a part of the community. Time passes slowly as it does at the beginning of a vacation. But as the novel progresses, and the area and its people become familiar to both Cress and the reader, the pace picks up. At the beginning of the novel, several chapters are spent on one season. By the end of the book, two months passes with a line break.

This is a novel about obsessive love and at some point during my reading of it, I became obsessed with the story in a way that surprised me. You could say my experience mirrored Cress’s own love affair, which starts out simply and easily but then somehow turns into a life-altering event that keeps Cress captive in the mountains for years. Although I wouldn’t characterize Off Course as a life-altering novel, it did cast a very strong spell. The fairy tale theme is pervasive and like all good fairy tales, there is a sense of unease, of darkness unseen. Cress describes her love as “a sad old king,” the arrival of spring is “a clear flammable gas in the air,” and a pocketknife is found buried in the dirt, like a bad omen.

It’s only when Cress descends to a lower elevation to visit friends that she realizes how strange her life has become:

…it was if she’d awakened from a dream or, more accurately, been dumped out of a fairy tale like the peasant girls who’d fallen down wells and found themselves in dark forests where animals talked and princes wandered disguised as beggars and you performed test after test until you woke up in your old bed, a silver flask the only proof of your ordeal.

The question of why Cressida finds herself in limbo haunts Off Course. She has everything going for her: she’s a well-educated young woman, from a well-off family, with a strong network of friends and acquaintances. She makes new friends easily and doesn’t have trouble finding work or places to live. She’s smart, resourceful, confident, and adaptable. So how does she lose her bearings? Huneven offers a number of ideas, including a Freudian one that, like so many Freudian clues, was so obvious in retrospect that I couldn’t believe I’d missed it. But no single explanation is put forth as the primary reason for Cress’s missteps. The mystery of those squandered years — and “squandered” is Cress’s word, not mine — remains unresolved in a way that feels very true to life.