1.

My grandmother died last November at ninety-six. I hadn’t seen her in thirteen years. The funeral was in Switzerland, where she’d lived for decades, and I went only because my mother asked me to. Twice.

My mother was nervous. She doesn’t like public-speaking in general, and I imagine the emotional stakes of this situation were high. She had had a complicated relationship with her mother. Standing in the chilly chapel, she turned to me and whispered, “I don’t think I’m going to make it.”

“You’ll be fine,” I said. “Just remember what an asshole she was.”

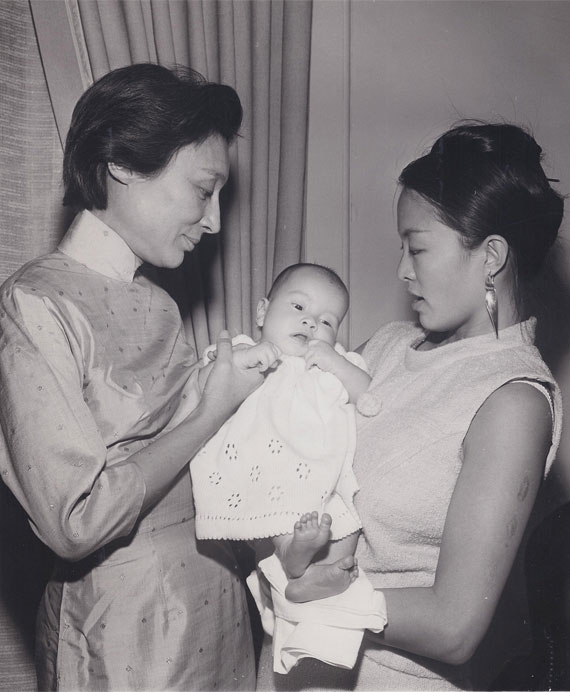

My grandmother, the writer Han Suyin, was born Mathilde Rosalie Claire Elizabeth Genevieve Chou in China in 1916 to a Belgian mother and a Chinese father, which makes her, genetically, my closest match in my extended family, though until her death and funeral, I had chosen not to think too carefully about what we share. I’m the daughter of a full-Chinese mother (adopted by my grandmother) and a Russian Jew. Ori-Yenta, my father used to call me. When I was born, my grandmother told my mother that it was lucky I was a girl, the implication being that mixed-race girls had it better than mixed-race boys. They may have had it better, but they didn’t have it very good. Certainly, she hadn’t had it easy. A younger sibling had died because no doctor, white or Asian, would touch the infant, and my grandmother’s own mother — who, to her credit, did touch her — nevertheless referred to her as “the yellowish object.” With that row to hoe, the yellowish object became a Eurasian force of nature, a woman who was fierce and charismatic, as well as chameleonlike and a master at control and getting what she wanted. “I do what I want,” she said in one interview. “That’s the leitmotiv of my life.” My father, even to her face, called her Dragon Lady.

I was hugely ambivalent about her. Was she someone to be emulated or deplored? She spoke and wrote in three languages, became a doctor and a writer, publishing over forty books across five decades. A self-appointed ambassador between East and West at a time when few foreigners had access to Communist China, she visited with Zhou Enlai a dozen times and with Mao Zedong as early as 1966. She was hosted by three members of the Gang of Four. She called the Cultural Revolution a “creative historical undertaking” and wrote laudatory biographies of Mao and Zhou. Her pen name, by the way, translates as “common little voice.”

She was a life-long apologist for the Communist regime and declared her roots to be in China but lived in Paris, New York, Hong Kong, and Switzerland. At one point, she wore only Bally shoes. All her winter coats were fur coats, and one of the only things I remember her teaching me was how to fold silk shirts with tissue paper so they wouldn’t wrinkle in a suitcase.

She ate chili peppers straight off the plant. How did she do that? I’d wonder as a child, grossed out and jealous all at once.

Over the years, I stared at her whenever I got the chance, drawn by the way a room’s energy inevitably centered on her. She had thick grey hair, chopped short, in which she was always losing her hands. She could silence a room with those hands. I witnessed countless moments when she would interrupt someone then outline the ways in which that person was very, very wrong. And I found myself feeling both admiration and sympathy for those who had been silenced. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve come to respect even more the scope of her work: biographies, autobiographies, and novels chronicling wars, love affairs, betrayals, and allegiances set everywhere from Belgium to Singapore, India to America. She had a wide-ranging imagination, which made her refusal to empathize with her loved ones that much more hurtful.

In a 1969 letter, she wishes me a happy fourth birthday, encloses some stamps for my collection, and hopes that I will grow up “to be a big, happy girl,” and then adds, “The little Chinese girls and boys are preparing to defend themselves in case they too are attacked and killed by American soldiers and burnt alive with napalm.” No reason her four-year-old granddaughter shouldn’t know what kind of atrocities were being committed in her name.

At her funeral that day in Switzerland, there were five eulogies. Like all the others, my mother spoke of her almost exclusively as a public figure, the good work she’d done to bridge all races of the world. This might’ve been less eloquent if the eulogists hadn’t all been family members.

2.

No wonder I’ve preferred not to think too much about what my grandmother and I share, but listening to all those eulogies, and spending three days with my mother in a tiny Swiss hotel room, I had to. She was Eurasian; I’m Eurasian. She was a writer; I’m a writer. In one of her memoirs, published when I was twelve, she writes, “Karen is so very much like me in some ways that it is almost unbelievable.” What could she possibly have observed in pre-teen me to allow her to make that claim? Since her death, it’s occurred to me that those aspects of a mixed-race identity — her protean nature, her desire to control information and the narratives made from it — that served her have served me, and may have enabled the least appealing parts of ourselves. Turns out it’s not just my grandmother who deserves my ambivalence.

Those who have been disenchanted with me over the years, reading this, might say: Dragon Lady. A woman with chameleonlike abilities. A master at getting what she wants. A control freak. Now who does that sound like?

My parents divorced when I was three, and with fearsome precocity, I learned how to play them off each other. If my mother left me for an hour when I was, say, six, I’d call my father and tell him that I was frightened and alone. He’d rush across town, and from the safety of my bedroom I’d listen to him chiding her, all of us together again. When she insisted I pack my own suitcase for my vacations with him, I’d leave out key items and when he’d help me unpack, I’d explain that I’d had to pack by myself. And we’d head off to the store for a new swimsuit, new sneakers, a better racquet.

Applying to college, I wrote my essay about the double-edged sword of being a part of two races without being fully either. I got in. My first published short story mined the exoticism and low-level abuse of a 1972 trip to China that my grandmother took my mother and me on.

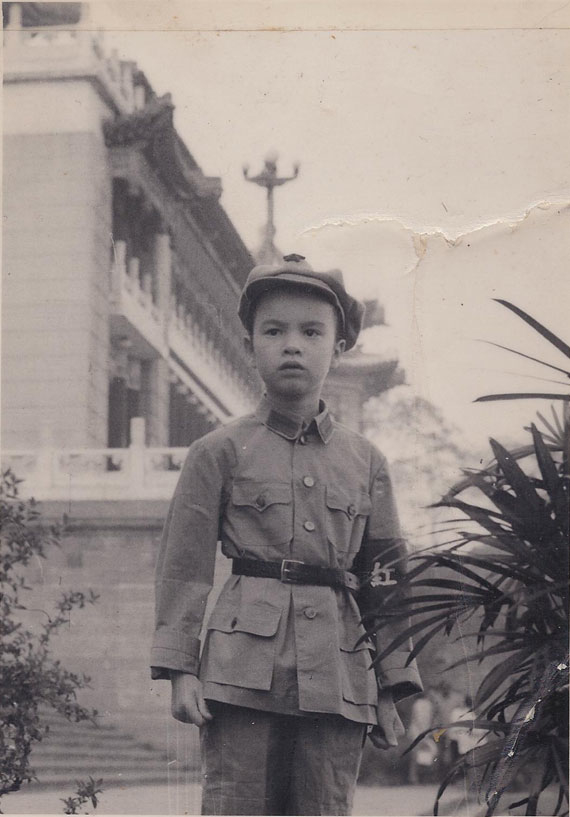

On that trip, wielding her Important Person status, my grandmother had a tailor work round the clock sewing me a Red Guard uniform. She had six-year-old me photographed in it the next morning. I’m saluting. She sent the photo to my father who went, as she knew he would, ballistic. He wasn’t big on political indoctrination.

More often than not, she used her imaginative abilities in the service of her own desires, remaining unabashed and unapologetic. “I never correct a word,” she said. “Sometimes I find that after many years have gone by, what you said at that time — even though it might have been castigated and damned as wrong — became right again.” Her books hurt some loved ones — as one put it, “It is truly unfortunate that she has a propensity sometimes to mix fact with fiction with unpleasant results for the persons concerned” — but she was absolutely certain of her authority to use that information. Yet when it came to some of her family’s most important stories, she denied information, or offered multiple, unreliable narratives. It’s been one of the great sadnesses of my mother’s life that despite endless requests, her mother provided only contradictory and evasive accounts of her biological parents’ identities. In one version, my grandmother bought my mother for a thousand yuan from a peasant family; in another, it’s a middle-class family with just one too many girls; in yet another, my mother is my grandfather’s illegitimate child, and my grandmother is the martyr.

That 1972 trip to China was meant to reintroduce my mother to her homeland — she had left when she was a young girl — and to introduce me to that half of my heritage. But the central agenda was to find my mother’s biological mother. In my grandmother’s memoir of the trip, she claims that she asked my mother if she’d like to see her mother, and my mother declined. This is not the way I remember it. I remember many requests made of many people during our time in Szechuan. I remember no one being able to track the woman down. We came the closest when we met with an old woman who had made my mother’s first pair of trousers. I remember we met beneath a banyan tree. There was no breeze. It was 107 in the shade. Mosquitoes circled my ankles. As the woman talked, she kept her eyes closed. She rolled her head around like someone feeling for the sun. No one translated for me, and I spent the meeting watching my mother. Even now, I remember her need, palpable in the thick air, and I remember my six-year-old impatience, an impatience I now understand was borne of jealousy, because I felt I had never had my mother’s attention the way this woman had it.

In my grandmother’s memoir, she expresses surprise that my mother didn’t want to meet her biological mother. But what I remember from that trip is a conversation I wasn’t supposed to hear. My grandmother’s special status had earned us the privilege of staying in a guest house for dignitaries as the only visitors. I woke from a nap to find my mother gone from our room. I went down to my grandmother’s suite to find them. I walked over a pale green carpet displaying scenes of Chairman Mao’s life in chronological order handmade by the members of an entire village to celebrate his last birthday.

At my grandmother’s room, the double doors were ajar. I stopped, looked through the space between door and door frame, and listened. They were talking about my mother’s mother. My mother lit a cigarette. I had never seen her smoke. My grandmother said, “She probably doesn’t even want to see you.” She said, “She did give you up.”

I don’t remember my mother’s reaction. I don’t remember talking to her about it later. I never told her what I overheard that day. There was no commiserating with her about the brutality of that moment. Whatever solace could’ve been offered was not. Over the years, I’ve had no trouble imagining how that comment must’ve made my mother feel. An ability to empathize was not the problem, and who did that sound like? What did I do with that memory? Years later, I wrote a short story about it.

3.

In the same book in which my grandmother claims how alike she and I were, she writes about me, “I have a fear that she may have…no time…to really grow into giving as well as taking.”

When my mother returns to the chair next to mine in that Swiss chapel, having just barely made it through her eulogy without falling apart, it is that moment in my grandmother’s book I think about. I whisper “Good job” to my mother the way I might to a pre-schooler, but that is all I offer. Why did I so often not offer what was clearly needed? Why is it that I have to imagine so many of the stories that matter so much to my mother? Because I have chosen not to ask. Me, the person who’s known even to passing strangers as the person who will ask anyone anything.

I was there in 1972 when my mother searched for her “real” mother and in 2012 when my mother lost the only mother she’d known. Her need was, and is, clear.

Some sort of nurturing or supportive presence: that’s what she was asking for when she asked me to come to the funeral. It was what she meant when before her eulogy she turned to me to say she wasn’t going to make it. It was what she was asking for the night after the funeral when, in a loud, busy café, she insisted on telling, in full, narratives from her life, a life that I already knew. Here, she was saying, I’m giving you something my mother could not give me: the stories we’ve shared to the best of my memory, to the best of my knowledge. And what had I given her back? Measured responses. Controlled reactions. The bare minimum. And who did that sound like?

I’ll come to the funeral, but I’ll only stay three days. I’ll tell you you’ll be fine giving the eulogy, but make a flippant comment that ignores your real panic. I know those stories, I’ll say not unkindly.

What could my grandmother have seen in a twelve-year-old me that made her say we were unbelievably alike? What is the single most important way in which my grandmother and I are alike? Our treatment of my mother. This is behavior I’m ashamed of, but I haven’t stopped. And if I’m being even more honest, I have to say that our mixed-race heritage may have more to do with that than I’d like to admit.

As mixed-race girls, we learned to take what we could from where we could to make a whole. That’s a vulnerable position to be in, susceptible to second-guessing and collapse, but it’s also a crash course in manipulation. Hence the posturing of invulnerability. The multitude of ways that my grandmother and I announced a lack of need, and presented ourselves as in solid control. We don’t need you, we projected, and therefore we may have to ignore what you need as we go about proving that to ourselves once and again. One of the only things I know how to say in Chinese is: Wo zi ze lai. I can help myself.

Certainly, my grandmother saw a lot of things when she looked at my mother, but just as certainly one of them was a Chinese woman: a clearly recognizable member of a group that my grandmother had spent her whole life trying to be accepted as a part of. And haven’t I, too, wished to be recognized as clearly one thing or another? As much as a mixed-race heritage has felt interesting and full, haven’t I also wished for the world to be able to look at me and recognize what they’re seeing?

The day I left Switzerland, my mother asked, “Don’t you think we could break the cycle?”

“What cycle?” I asked.

“Of control,” she said.

“Oh,” I said, knowing what she meant: that relinquishing control has always been the hardest thing for all three of us. “I would say that our relationship is a whole lot better than your relationship with Grandma was.”

And it is. But my mother was quiet for the rest of the taxi ride to the airport because that wasn’t really what she had asked, was it?

I rationalized: I wasn’t as bad as Grandma. I may have kept my solace to myself, but I’d never been as brutal as Grandma could be. And then a few weeks after the funeral, my mother came to visit. I picked her up at the bus station. She opted for the five-hour bus trip instead of the two-hour train so I didn’t have to drive the hour to the train station. Her conversation was full of the logistics of the will, the squabbling with the other heirs. She was unhappy with the will, suspected my grandmother had been duped in various ways. It was about ethics, she kept insisting.

Back at the house, impatient, I said, “Look, mom. You’re in emotional competition with these people.”

She insisted it was not about emotions.

“Please,” I said, so sure of my psychological reasoning. “This is about who Grandma loved more. And the one person who could’ve solved that problem for you when she was alive chose not to. And now she’s dead, so you’re going to have to do this on your own.” Then I told her I couldn’t talk to her about this anymore.

I silenced the room; I implied she was very, very wrong. And then I left.

4.

When my mother left home to go to college, my grandmother threw away almost everything she left behind. Stuffed animals, handmade dolls with suitcases full of outfits, books. Photographs. Drawings of the houses they had lived in, the pets they had had. Diaries.

I think about that now, months after I said those things to my mother. My mother coming home to discover the artifacts used to recognize the only life she knew, discarded. She may be full Chinese, recognizable to others, but unlike her, my grandmother and I were recognizable to ourselves. Our lifelong insistence on controlling our own narratives, ignoring what didn’t fit, had protected us from anyone’s versions but our own. These are understandings I wouldn’t have had without experiencing the funeral with my mother. These are understandings I haven’t yet shared with my mother.

I imagine my mother coming home for the holidays, standing in the doorway to what used to be her room, and taking breaths before asking why; my grandmother looking into the neater, tidier room and telling her she was far too old for all that stuff, before she moved on down the hallway: this, knowing them, was how it must have gone. My heart breaks for my mother. But, knowing me, this essay is the only sharing with her I’m likely to do.

Images courtesy the author.