1.

I was recently fired for the first time. When I was hired I had harbored no illusions this would be a job I would love or at which I would even modestly excel; instead, I thought it was a job I could do to a perfunctory degree of competence. In the interview, my future boss looked over my resume and asked me basic questions about my schedule and experience before describing the tasks and required skills. The subject was popular economics, and the job—as a research assistant—would be mostly image searching, he said, with some fact checking and occasional reporting. When he finished, he turned and looked at me: “Does this sound like something you could do?”

I was recently fired for the first time. When I was hired I had harbored no illusions this would be a job I would love or at which I would even modestly excel; instead, I thought it was a job I could do to a perfunctory degree of competence. In the interview, my future boss looked over my resume and asked me basic questions about my schedule and experience before describing the tasks and required skills. The subject was popular economics, and the job—as a research assistant—would be mostly image searching, he said, with some fact checking and occasional reporting. When he finished, he turned and looked at me: “Does this sound like something you could do?”

We were sitting next to each other in oversized armchairs and my resume lay on the coffee table in front of us. It was the silent third party in these negotiations, and I couldn’t tell whose side it was on. I had recently made its verbs more active and its alignments more precise, and the result was, without a doubt, an attractive piece of paper. My education, work experience, and skills and interests fit onto a single page, appearing neither cramped, nor as if I were unaccomplished. I had experience with both books and periodicals, and had paid my dues while also gaining some management experience. According to my resume, I had the skills to do the job.

Still, I hesitated. I stared at the piece of paper, wishing it could talk, that we could excuse ourselves into the other room and confer as to the best course of action. Instead the thing sat there, flat and silent, and I was on my own to weigh pros and cons. Deadlines were not an issue, but the subject matter would be since I am as good at economics as I am at being an astronaut. That said, it was pop economics, which would be a stretch for me but a stretch I could maybe make. I don’t like fact checking but I have experience with it, and while talking on the telephone isn’t my favorite thing to do, I can do it the way I used to run laps around the gym. I met the gaze of my future boss: “Yes,” I said. “I think this is something I could do.”

Two and a half months later, he called to tell me our time together was over. The night before I had sent him images of the wrong radio towers from the turn of the century for the second time in a row. It had been late and I didn’t know where on the internet to find the right ones but excuses had ceased to matter: I had made so many mistakes by then that adding another to the list was what the job had become. It wasn’t that I didn’t care about the job or like my boss; I both cared about the job and liked my boss; I was just empirically bad at the work.

After we hung up, I stared at the computer screen. I was not happy about having been fired, but I was relieved I wouldn’t have to wake up the next morning knowing it was a foregone conclusion I would spend my working hours professionally underperforming. I had had a feeling this would happen, but it was a feeling I hadn’t wanted to face because it meant admitting that the few skills I had accrued over my thirty years were even less flexible than I feared: Being able to talk to people about poetry or folk music or their lives in general did not translate into being able to research trivia about car seat fatality statistics in the 1950s. The worst part about getting fired, however, was that it prompted the question, “What now?” to which I didn’t—and don’t—have an answer.

2.

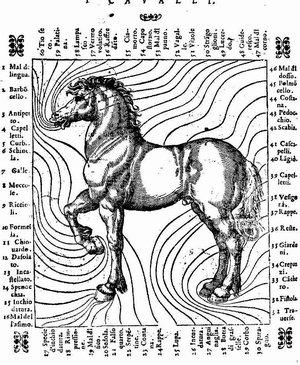

Starting early—as young as four or five—I was one of those girls who was obsessed with horses. I had the books and the Breyer models and, sometimes, I ran around in the yard or the street pretending to be one. It wasn’t long into the obsession before I began asking my father—architect, urban planner, humble university professor—for a pony. The first time I asked I was six and my father’s response was that if I wanted a pony I should plan on becoming an investment banker. When I asked him what an investment banker was his definition was, “Someone who makes enough money to have a pony.” This was when I understood that money is one of life’s confounding questions.

Starting early—as young as four or five—I was one of those girls who was obsessed with horses. I had the books and the Breyer models and, sometimes, I ran around in the yard or the street pretending to be one. It wasn’t long into the obsession before I began asking my father—architect, urban planner, humble university professor—for a pony. The first time I asked I was six and my father’s response was that if I wanted a pony I should plan on becoming an investment banker. When I asked him what an investment banker was his definition was, “Someone who makes enough money to have a pony.” This was when I understood that money is one of life’s confounding questions.

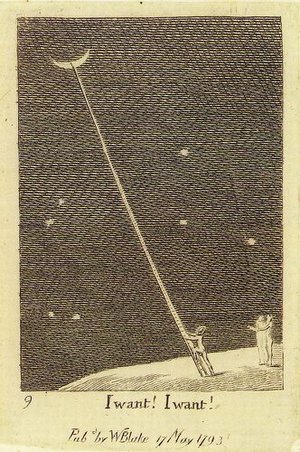

There’s a famous drawing by William Blake of a figure standing at the bottom of a ladder that leads to the moon. The figure is reaching skyward; the caption reads, “I want! I want!” and seems to perfectly illustrate my relationship to my career, such as it is: I am on the ground while this career of mine lurks in the dark nearly 400,000 miles distant. After I got over wanting to be an investment banker for the ponies the profession could afford me, I went through phases of wanting to be a professional horseback rider, a folk singer, a Supreme Court justice, a vintner, a personal shopper, and a writer. While none of these—save scoring a spot on the Supreme Court—is a particularly lucrative career choice, the choice of writer is perhaps the least so of all. This makes it especially unfortunate that wanting to be a writer is the only one that stuck.

By the time I graduated from college, enough people had told me I couldn’t make a living this way for me to begin trying to jury rig my skills and interests into skills and interests that paid. I worked as an English teacher, a crime reporter, a waitress, a library assistant, and as a research assistant for authors. With each job I told myself it was temporary: just a job until I could forge a writing career. Alas, the most money I’ve ever earned for a piece of writing I’ve written because I wanted to write it is $50, and that was a month ago. Until recently I had—naively—not considered fully demoting my future writing career to past, present, and future hobby, but the reality is that the time has past come. I’ve paid the rent these ten years by looking at my resume and telling myself to “Make it work,” as well as with some generous support from my family. I now see that writing is proving at least as costly as a pony could have ever been.

It’s true: I worry sometimes that writing has gone the way of the pony, that it is no longer a way to help work the farm but—as it’s been said before—has become a pastime only for those who can afford it, and among whom I do not number. This is also when I feel as if I am beating back the tumbleweeds of cynicism with a piece of string. I try to turn the analogy around, repeating to myself the cliché that a writer is not what you are but who you are. By this logic, writers are the ponies. Because we can’t afford to keep ourselves, we hire ourselves out to humans. In the best case scenarios we like our humans and enjoy the challenges of what they have us do. Indeed, under their guidance we are able to do things we never thought possible: pirouette and jump over fences as tall as we are. In the worst-case scenarios we end up foul-tempered in a stall, pinning our ears to the backs of our heads and gnashing our teeth whenever someone tries to come in and tack us up.

Sometimes, too, while trying to jump fences, we don’t quite make it over cleanly: a rail comes tumbling to the ground or we do. We’re usually able to pick ourselves up long enough to exit the ring with dignity, but in the more dramatic mishaps, there are those inevitable moments after the fall when we are running around the ring, spooked and directionless, broken reins swinging wildly and in danger of tripping us again.

3.

I would be lying of course if I didn’t admit I fell harder than I initially may have thought. The days and weeks following my firing were the first time I admitted to myself that instead of building a Blakeian ladder to the moon that could hold my weight, maybe I have been building one bound to collapse, constructed from toothpicks all along. When I build again I want it to be with real wood and nails, and maybe propped this time against a new and different moon.

Resumes are funny things because they are pieces of paper on which we are supposed appear both professional and human, which, with any luck, we are. When I look at my resume and consider the left turns I could make at this career crossroads, I am forced to consider what my skills and interests truly are. According to my resume, my skills and interests include, traveling, eating food and drinking wine, playing music, cuddling with homeless animals, contemporary design, MS Word, and MacIntosh and PC platforms. While I like to think these things are true, I hope I have other, less canned attributes. Perhaps, too, when these are combined, a picture of my strengths might emerge with an eye to job placement. I sometimes play with the idea of creating a resume that relegates Education and Work Experience to a few lines at the bottom of the piece of paper, and instead gives the featured slot to my Skills and Interests. Each skill and interest would be put into resume-speak and bullet pointed:

- Imaginary degree in angling furniture.

- High tolerance for busy work.

- Ability to pee efficiently in public restrooms.

- Precision sweeper.

- Passion for shunning umbrellas in favor of getting wet.

- Petfinder.com

- Open to criticism of clog wearing.

- Adept at hating brunch.

- Self-taught in the art of having feelings.

- Pretty good at sharing.

- Communicating via face every thought that passes through brain.

- Eager to jump to tragic conclusions about temporary illnesses.

- Prompt to excuse self after belching.

- Laughs loudly, often, at other people’s jokes.

Looking at the list now, it seems my skills and interests qualify me for nothing other than being myself, which was at least part of the problem to begin with: I can’t get paid for being me, nor should I be and nor do I want to be. Keeping a running list of my skills and interests is only a beginning. Since I am by now a fully formed human being, it is a beginning I can only hope won’t take another 30 years to maneuver in my favor.

4.

I write this as the mail is piling up on my kitchen counter, more than half of which is bills and monthly statements from Bank of America that I am afraid to open. The rest is from my alma mater asking me to give them all the money I don’t already owe to credit cards, hospitals and my therapist. I already know I owe more money than I have and I don’t want to see the cold hard evidence written out on paper. When I visit my parents the time always comes when my father sits me down and says, “So, how’s your bank account?” as if my bank account were a member of the family. It practically is—the ugly stepchild—and I treat it accordingly. I tell him it’s fine or at least that it was the last time I hung out with it. I don’t tell him I can’t remember the last time this was because, the truth is, I don’t want him to have to worry about it and I am wracked with guilt that he does and that he has to.

Once upon a time my father wanted to be a painter. He became an architect instead because the schooling pardoned him from the draft and the degree would let him afford a family. I know he has felt conflicted about this decision his entire life—that he felt forced into it by his parents when he was young and trying to figure out how to make his way.

I know because I have watched him struggle for years with how he should advise me to proceed with my life. Moments after he suggests I try advertising or television as a career move, he backtracks and says I should do something that makes me happy, to not give up on this writing thing quite yet.

He’ll then hedge–money makes things easier–before telling me again. Keep writing.

[Image credits: Images from Fiaschi’s book, J Mark Dodds]