Mentioned in:

Most Anticipated: The Great Spring 2024 Preview

April

April 2

Women! In! Peril! by Jessie Ren Marshall [F]

For starters, excellent title. This debut short story collection from playwright Marshall spans sex bots and space colonists, wives and divorcées, prodding at the many meanings of womanhood. Short story master Deesha Philyaw, also taken by the book's title, calls this one "incisive! Provocative! And utterly satisfying!" —Sophia M. Stewart

The Audacity by Ryan Chapman [F]

This sophomore effort, after the darkly sublime absurdity of Riots I have Known, trades in the prison industrial complex for the Silicon Valley scam. Chapman has a sharp eye and a sharper wit, and a book billed as a "bracing satire about the implosion of a Theranos-like company, a collapsing marriage, and a billionaires’ 'philanthropy summit'" promises some good, hard laughs—however bitter they may be—at the expense of the über-rich. —John H. Maher

The Obscene Bird of Night by José Donoso, tr. Leonard Mades [F]

I first learned about this book from an essay in this publication by Zachary Issenberg, who alternatively calls it Donoso's "masterpiece," "a perfect novel," and "the crowning achievement of the gothic horror genre." He recommends going into the book without knowing too much, but describes it as "a story assembled from the gossip of society’s highs and lows, which revolves and blurs into a series of interlinked nightmares in which people lose their memory, their sex, or even their literal organs." —SMS

Globetrotting ed. Duncan Minshull [NF]

I'm a big walker, so I won't be able to resist this assemblage of 50 writers—including Edith Wharton, Katharine Mansfield, Helen Garner, and D.H. Lawrence—recounting their various journeys by foot, edited by Minshull, the noted walker-writer-anthologist behind The Vintage Book of Walking (2000) and Where My Feet Fall (2022). —SMS

All Things Are Too Small by Becca Rothfeld [NF]

Hieronymus Bosch, eat your heart out! The debut book from Rothfeld, nonfiction book critic at the Washington Post, celebrates our appetite for excess in all its material, erotic, and gluttonous glory. Covering such disparate subjects from decluttering to David Cronenberg, Rothfeld looks at the dire cultural—and personal—consequences that come with adopting a minimalist sensibility and denying ourselves pleasure. —Daniella Fishman

A Good Happy Girl by Marissa Higgins [F]

Higgins, a regular contributor here at The Millions, debuts with a novel of a young woman who is drawn into an intense and all-consuming emotional and sexual relationship with a married lesbian couple. Halle Butler heaps on the praise for this one: “Sometimes I could not believe how easily this book moved from gross-out sadism into genuine sympathy. Totally surprising, totally compelling. I loved it.” —SMS

City Limits by Megan Kimble [NF]

As a Los Angeleno who is steadily working my way through The Power Broker, this in-depth investigation into the nation's freeways really calls to me. (Did you know Robert Moses couldn't drive?) Kimble channels Caro by locating the human drama behind freeways and failures of urban planning. —SMS

We Loved It All by Lydia Millet [NF]

Planet Earth is a pretty awesome place to be a human, with its beaches and mountains, sunsets and birdsong, creatures great and small. Millet, a creative director at the Center for Biological Diversity in Tucson, infuses her novels with climate grief and cautions against extinction, and in this nonfiction meditation, she makes a case for a more harmonious coexistence between our species and everybody else in the natural world. If a nostalgic note of “Auld Lang Syne” trembles in Millet’s title, her personal anecdotes and public examples call for meaningful environmental action from local to global levels. —Nathalie op de Beeck

Like Love by Maggie Nelson [NF]

The new book from Nelson, one of the most towering public intellectuals alive today, collects 20 years of her work—including essays, profiles, and reviews—that cover disparate subjects, from Prince and Kara Walker to motherhood and queerness. For my fellow Bluets heads, this will be essential reading. —SMS

Traces of Enayat by Iman Mersal, tr. Robin Moger [NF]

Mersal, one of the preeminent poets of the Arabic-speaking world, recovers the life, work, and legacy of the late Egyptian writer Enayat al-Zayyat in this biographical detective story. Mapping the psyche of al-Zayyat, who died by suicide in 1963, alongside her own, Mersal blends literary mystery and memoir to produce a wholly original portrait of two women writers. —SMS

The Letters of Emily Dickinson ed. Cristanne Miller and Domhnall Mitchell [NF]

The letters of Emily Dickinson, one of the greatest and most beguiling of American poets, are collected here for the first time in nearly 60 years. Her correspondence not only gives access to her inner life and social world, but reveal her to be quite the prose stylist. "In these letters," says Jericho Brown, "we see the life of a genius unfold." Essential reading for any Dickinson fan. —SMS

April 9

Short War by Lily Meyer [F]

The debut novel from Meyer, a critic and translator, reckons with the United States' political intervention in South America through the stories of two generations: a young couple who meet in 1970s Santiago, and their American-born child spending a semester Buenos Aires. Meyer is a sharp writer and thinker, and a great translator from the Spanish; I'm looking forward to her fiction debut. —SMS

There's Going to Be Trouble by Jen Silverman [F]

Silverman's third novel spins a tale of an American woman named Minnow who is drawn into a love affair with a radical French activist—a romance that, unbeknown to her, mirrors a relationship her own draft-dodging father had against the backdrop of the student movements of the 1960s. Teasing out the intersections of passion and politics, There's Going to Be Trouble is "juicy and spirited" and "crackling with excitement," per Jami Attenberg. —SMS

Table for One by Yun Ko-eun, tr. Lizzie Buehler [F]

I thoroughly enjoyed Yun Ko-eun's 2020 eco-thriller The Disaster Tourist, also translated by Buehler, so I'm excited for her new story collection, which promises her characteristic blend of mundanity and surrealism, all in the name of probing—and poking fun—at the isolation and inanity of modern urban life. —SMS

Playboy by Constance Debré, tr. Holly James [NF]

The prequel to the much-lauded Love Me Tender, and the first volume in Debré's autobiographical trilogy, Playboy's incisive vignettes explore the author's decision to abandon her marriage and career and pursue the precarious life of a writer, which she once told Chris Kraus was "a bit like Saint Augustine and his conversion." Virginie Despentes is a fan, so I'll be checking this out. —SMS

Native Nations by Kathleen DuVal [NF]

DuVal's sweeping history of Indigenous North America spans a millennium, beginning with the ancient cities that once covered the continent and ending with Native Americans' continued fight for sovereignty. A study of power, violence, and self-governance, Native Nations is an exciting contribution to a new canon of North American history from an Indigenous perspective, perfect for fans of Ned Blackhawk's The Rediscovery of America. —SMS

Personal Score by Ellen van Neerven [NF]

I’ve always been interested in books that drill down on a specific topic in such a way that we also learn something unexpected about the world around us. Australian writer Van Neerven's sports memoir is so much more than that, as they explore the relationship between sports and race, gender, and sexuality—as well as the paradox of playing a colonialist sport on Indigenous lands. Two Dollar Radio, which is renowned for its edgy list, is publishing this book, so I know it’s going to blow my mind. —Claire Kirch

April 16

The Notebooks of Sonny Rollins by Sonny Rollins [NF]

The musings, recollections, and drawings of jazz legend Sonny Rollins are collected in this compilation of his precious notebooks, which he began keeping in 1959, the start of what would become known as his “Bridge Years,” during which he would practice at all hours on the Williamsburg Bridge. Rollins chronicles everything from his daily routine to reflections on music theory and the philosophical underpinnings of his artistry. An indispensable look into the mind and interior life of one of the most celebrated jazz musicians of all time. —DF

Henry Henry by Allen Bratton [F]

Bratton’s ambitious debut reboots Shakespeare’s Henriad, landing Hal Lancaster, who’s in line to be the 17th Duke of Lancaster, in the alcohol-fueled queer party scene of 2014 London. Hal’s identity as a gay man complicates his aristocratic lineage, and his dalliances with over-the-hill actor Jack Falstaff and promising romance with one Harry Percy, who shares a name with history’s Hotspur, will have English majors keeping score. Don’t expect a rom-com, though. Hal’s fraught relationship with his sexually abusive father, and the fates of two previous gay men from the House of Lancaster, lend gravity to this Bard-inspired take. —NodB

Bitter Water Opera by Nicolette Polek [F]

Graywolf always publishes books that make me gasp in awe and this debut novel, by the author of the entrancing 2020 story collection Imaginary Museums, sounds like it’s going to keep me awake at night as well. It’s a tale about a young woman who’s lost her way and writes a letter to a long-dead ballet dancer—who then visits her, and sets off a string of strange occurrences. —CK

Norma by Sarah Mintz [F]

Mintz's debut novel follows the titular widow as she enjoys her newfound freedom by diving headfirst into her surrounds, both IRL and online. Justin Taylor says, "Three days ago I didn’t know Sarah Mintz existed; now I want to know where the hell she’s been all my reading life. (Canada, apparently.)" —SMS

What Kingdom by Fine Gråbøl, tr. Martin Aitken [F]

A woman in a psychiatric ward dreams of "furniture flickering to life," a "chair that greets you," a "bookshelf that can be thrown on like an apron." This sounds like the moving answer to the otherwise puzzling question, "What if the Kantian concept of ding an sich were a novel?" —JHM

Weird Black Girls by Elwin Cotman [F]

Cotman, the author of three prior collections of speculative short stories, mines the anxieties of Black life across these seven tales, each of them packed with pop culture references and supernatural conceits. Kelly Link calls Cotman's writing "a tonic to ward off drabness and despair." —SMS

Presence by Tracy Cochran [NF]

Last year marked my first earnest attempt at learning to live more mindfully in my day-to-day, so I was thrilled when this book serendipitously found its way into my hands. Cochran, a New York-based meditation teacher and Tibetan Buddhist practitioner of 50 years, delivers 20 psycho-biographical chapters on recognizing the importance of the present, no matter how mundane, frustrating, or fortuitous—because ultimately, she says, the present is all we have. —DF

Committed by Suzanne Scanlon [NF]

Scanlon's memoir uses her own experience of mental illness to explore the enduring trope of the "madwoman," mining the work of Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Virginia Woolf, Sylvia Plath, Audre Lorde, and others for insights into the long literary tradition of women in psychological distress. The blurbers for this one immediately caught my eye, among them Natasha Trethewey, Amina Cain, and Clancy Martin, who compares Scanlon's work here to that of Marguerite Duras. —SMS

Unrooted by Erin Zimmerman [NF]

This science memoir explores Zimmerman's journey to botany, a now endangered field. Interwoven with Zimmerman's experiences as a student and a mother is an impassioned argument for botany's continued relevance and importance against the backdrop of climate change—a perfect read for gardeners, plant lovers, or anyone with an affinity for the natural world. —SMS

April 23

Reboot by Justin Taylor [F]

Extremely online novels, as a rule, have become tiresome. But Taylor has long had a keen eye for subcultural quirks, so it's no surprise that PW's Alan Scherstuhl says that "reading it actually feels like tapping into the internet’s best celeb gossip, fiercest fandom outrages, and wildest conspiratorial rabbit holes." If that's not a recommendation for the Book Twitter–brained reader in you, what is? —JHM

Divided Island by Daniela Tarazona, tr. Lizzie Davis and Kevin Gerry Dunn [F]

A story of multiple personalities and grief in fragments would be an easy sell even without this nod from Álvaro Enrigue: "I don't think that there is now, in Mexico, a literary mind more original than Daniela Tarazona's." More original than Mario Bellatin, or Cristina Rivera Garza? This we've gotta see. —JHM

Prairie, Dresses, Art, Other by Danielle Dutton [NF]

Coffee House Press has for years relished its reputation for publishing “experimental” literature, and this collection of short stories and essays about literature and art and the strangeness of our world is right up there with the rest of Coffee House’s edgiest releases. Don’t be fooled by the simple cover art—Dutton’s work is always formally inventive, refreshingly ambitious, and totally brilliant. —CK

I Just Keep Talking by Nell Irvin Painter [NF]

I first encountered Nell Irvin Painter in graduate school, as I hung out with some Americanists who were her students. Painter was always a dazzling, larger-than-life figure, who just exuded power and brilliance. I am so excited to read this collection of her essays on history, literature, and politics, and how they all intersect. The fact that this collection contains Painter’s artwork is a big bonus. —CK

April 30

Real Americans by Rachel Khong [F]

The latest novel from Khong, the author of Goodbye, Vitamin, explores class dynamics and the illusory American Dream across generations. It starts out with a love affair between an impoverished Chinese American woman from an immigrant family and an East Coast elite from a wealthy family, before moving us along 21 years: 15-year-old Nick knows that his single mother is hiding something that has to do with his biological father and thus, his identity. C Pam Zhang deems this "a book of rare charm," and Andrew Sean Greer calls it "gorgeous, heartfelt, soaring, philosophical and deft." —CK

The Swans of Harlem by Karen Valby [NF]

Huge thanks to Bebe Neuwirth for putting this book on my radar (she calls it "fantastic") with additional gratitude to Margo Jefferson for sealing the deal (she calls it "riveting"). Valby's group biography of five Black ballerinas who forever transformed the art form at the height of the Civil Rights movement uncovers the rich and hidden history of Black ballet, spotlighting the trailblazers who paved the way for the Misty Copelands of the world. —SMS

Appreciation Post by Tara Ward [NF]

Art historian Ward writes toward an art history of Instagram in Appreciation Post, which posits that the app has profoundly shifted our long-established ways of interacting with images. Packed with cultural critique and close reading, the book synthesizes art history, gender studies, and media studies to illuminate the outsize role that images play in all of our lives. —SMS

May

May 7

Bad Seed by Gabriel Carle, tr. Heather Houde [F]

Carle’s English-language debut contains echoes of Denis Johnson’s Jesus’s Son and Mariana Enriquez’s gritty short fiction. This story collection haunting but cheeky, grim but hopeful: a student with HIV tries to avoid temptation while working at a bathhouse; an inebriated friend group witnesses San Juan go up in literal flames; a sexually unfulfilled teen drowns out their impulses by binging TV shows. Puerto Rican writer Luis Negrón calls this “an extraordinary literary debut.” —Liv Albright

The Lady Waiting by Magdalena Zyzak [F]

Zyzak’s sophomore novel is a nail-biting delight. When Viva, a young Polish émigré, has a chance encounter with an enigmatic gallerist named Bobby, Viva’s life takes a cinematic turn. Turns out, Bobby and her husband have a hidden agenda—they plan to steal a Vermeer, with Viva as their accomplice. Further complicating things is the inevitable love triangle that develops among them. Victor LaValle calls this “a superb accomplishment," and Percival Everett says, "This novel pops—cosmopolitan, sexy, and funny." —LA

América del Norte by Nicolás Medina Mora [F]

Pitched as a novel that "blends the Latin American traditions of Roberto Bolaño and Fernanda Melchor with the autofiction of U.S. writers like Ben Lerner and Teju Cole," Mora's debut follows a young member of the Mexican elite as he wrestles with questions of race, politics, geography, and immigration. n+1 co-editor Marco Roth calls Mora "the voice of the NAFTA generation, and much more." —SMS

How It Works Out by Myriam Lacroix [F]

LaCroix's debut novel is the latest in a strong early slate of novels for the Overlook Press in 2024, and follows a lesbian couple as their relationship falls to pieces across a number of possible realities. The increasingly fascinating and troubling potentialities—B-list feminist celebrity, toxic employer-employee tryst, adopting a street urchin, cannibalism as relationship cure—form a compelling image of a complex relationship in multiversal hypotheticals. —JHM

Cinema Love by Jiaming Tang [F]

Ting's debut novel, which spans two continents and three timelines, follows two gay men in rural China—and, later, New York City's Chinatown—who frequent the Workers' Cinema, a movie theater where queer men cruise for love. Robert Jones, Jr. praises this one as "the unforgettable work of a patient master," and Jessamine Chan calls it "not just an extraordinary debut, but a future classic." —SMS

First Love by Lilly Dancyger [NF]

Dancyger's essay collection explores the platonic romances that bloom between female friends, giving those bonds the love-story treatment they deserve. Centering each essay around a formative female friendship, and drawing on everything from Anaïs Nin and Sylvia Plath to the "sad girls" of Tumblr, Dancyger probes the myriad meanings and iterations of friendship, love, and womanhood. —SMS

See Loss See Also Love by Yukiko Tominaga [F]

In this impassioned debut, we follow Kyoko, freshly widowed and left to raise her son alone. Through four vignettes, Kyoko must decide how to raise her multiracial son, whether to remarry or stay husbandless, and how to deal with life in the face of loss. Weike Wang describes this one as “imbued with a wealth of wisdom, exploring the languages of love and family.” —DF

The Novices of Lerna by Ángel Bonomini, tr. Jordan Landsman [F]

The Novices of Lerna is Landsman's translation debut, and what a way to start out: with a work by an Argentine writer in the tradition of Jorge Luis Borges and Adolfo Bioy Casares whose work has never been translated into English. Judging by the opening of this short story, also translated by Landsman, Bonomini's novel of a mysterious fellowship at a Swiss university populated by doppelgängers of the protagonist is unlikely to disappoint. —JHM

Black Meme by Legacy Russell [NF]

Russell, best known for her hit manifesto Glitch Feminism, maps Black visual culture in her latest. Black Meme traces the history of Black imagery from 1900 to the present, from the photograph of Emmett Till published in JET magazine to the footage of Rodney King's beating at the hands of the LAPD, which Russell calls the first viral video. Per Margo Jefferson, "You will be galvanized by Legacy Russell’s analytic brilliance and visceral eloquence." —SMS

The Eighth Moon by Jennifer Kabat [NF]

Kabat's debut memoir unearths the history of the small Catskills town to which she relocated in 2005. The site of a 19th-century rural populist uprising, and now home to a colorful cast of characters, the Appalachian community becomes a lens through which Kabat explores political, economic, and ecological issues, mining the archives and the work of such writers as Adrienne Rich and Elizabeth Hardwick along the way. —SMS

Stories from the Center of the World ed. Jordan Elgrably [F]

Many in America hold onto broad, centuries-old misunderstandings of Arab and Muslim life and politics that continue to harm, through both policy and rhetoric, a perpetually embattled and endangered region. With luck, these 25 tales by writers of Middle Eastern and North African origin might open hearts and minds alike. —JHM

An Encyclopedia of Gardening for Colored Children by Jamaica Kincaid and Kara Walker [NF]

Two of the most brilliant minds on the planet—writer Jamaica Kincaid and visual artist Kara Walker—have teamed up! On a book! About plants! A dream come true. Details on this slim volume are scant—see for yourself—but I'm counting down the minutes till I can read it all the same. —SMS

Physics of Sorrow by Georgi Gospodinov, tr. Angela Rodel [F]

I'll be honest: I would pick up this book—by the International Booker Prize–winning author of Time Shelter—for the title alone. But also, the book is billed as a deeply personal meditation on both Communist Bulgaria and Greek myth, so—yep, still picking this one up. —JHM

May 14

This Strange Eventful History by Claire Messud [F]

I read an ARC of this enthralling fictionalization of Messud’s family history—people wandering the world during much of the 20th century, moving from Algeria to France to North America— and it is quite the story, with a postscript that will smack you on the side of the head and make you re-think everything you just read. I can't recommend this enough. —CK

Woodworm by Layla Martinez, tr. Sophie Hughes and Annie McDermott [F]

Martinez’s debut novel takes cabin fever to the max in this story of a grandmother, granddaughter, and their haunted house, set against the backdrop of the Spanish Civil War. As the story unfolds, so do the house’s secrets, the two women must learn to collaborate with the malevolent spirits living among them. Mariana Enriquez says that this "tense, chilling novel tells a story of specters, class war, violence, and loneliness, as naturally as if the witches had dictated this lucid, terrible nightmare to Martínez themselves.” —LA

Self Esteem and the End of the World by Luke Healy [NF]

Ah, writers writing about writing. A tale as old as time, and often timeworn to boot. But graphic novelists graphically noveling about graphic novels? (Verbing weirds language.) It still feels fresh to me! Enter Healy's tale of "two decades of tragicomic self-discovery" following a protagonist "two years post publication of his latest book" and "grappling with his identity as the world crumbles." —JHM

All Fours by Miranda July [F]

In excruciating, hilarious detail, All Fours voices the ethically dubious thoughts and deeds of an unnamed 45-year-old artist who’s worried about aging and her capacity for desire. After setting off on a two-week round-trip drive from Los Angeles to New York City, the narrator impulsively checks into a motel 30 miles from her home and only pretends to be traveling. Her flagrant lies, unapologetic indolence, and semi-consummated seduction of a rent-a-car employee set the stage for a liberatory inquisition of heteronorms and queerness. July taps into the perimenopause zeitgeist that animates Jen Beagin’s Big Swiss and Melissa Broder’s Death Valley. —NodB

Love Junkie by Robert Plunket [F]

When a picture-perfect suburban housewife's life is turned upside down, a chance brush with New York City's gay scene launches her into gainful, albeit unconventional, employment. Set at the dawn of the AIDs epidemic, Mimi Smithers, described as a "modern-day Madame Bovary," goes from planning parties in Westchester to selling used underwear with a Manhattan porn star. As beloved as it is controversial, Plunket's 1992 cult novel will get a much-deserved second life thanks to this reissue by New Directions. (Maybe this will finally galvanize Madonna, who once optioned the film rights, to finally make that movie.) —DF

Tomorrowing by Terry Bisson [F]

The newest volume in Duke University’s Practices series collects for the first time the late Terry Bisson’s Locus column "This Month in History," which ran for two decades. In it, the iconic "They’re Made Out of Meat" author weaves an alt-history of a world almost parallel to ours, featuring AI presidents, moon mountain hikes, a 196-year-old Walt Disney’s resurrection, and a space pooch on Mars. This one promises to be a pure spectacle of speculative fiction. —DF

Chop Fry Watch Learn by Michelle T. King [NF]

A large portion of the American populace still confuses Chinese American food with Chinese food. What a delight, then, to discover this culinary history of the worldwide dissemination of that great cuisine—which moonlights as a biography of Chinese cookbook and TV cooking program pioneer Fu Pei-mei. —JHM

On the Couch ed. Andrew Blauner [NF]

André Aciman, Susie Boyt, Siri Hustvedt, Rivka Galchen, and Colm Tóibín are among the 25 literary luminaries to contribute essays on Freud and his complicated legacy to this lively volume, edited by writer, editor, and literary agent Blauner. Taking tacts both personal and psychoanalytical, these essays paint a fresh, full picture of Freud's life, work, and indelible cultural impact. —SMS

Another Word for Love by Carvell Wallace [NF]

Wallace is one of the best journalists (and tweeters) working today, so I'm really looking forward to his debut memoir, which chronicles growing up Black and queer in America, and navigating the world through adulthood. One of the best writers working today, Kiese Laymon, calls Another Word for Love as “One of the most soulfully crafted memoirs I’ve ever read. I couldn’t figure out how Carvell Wallace blurred time, region, care, and sexuality into something so different from anything I’ve read before." —SMS

The Devil's Best Trick by Randall Sullivan [NF]

A cultural history interspersed with memoir and reportage, Sullivan's latest explores our ever-changing understandings of evil and the devil, from Egyptian gods and the Book of Job to the Salem witch trials and Black Mass ceremonies. Mining the work of everyone from Zoraster, Plato, and John Milton to Edgar Allen Poe, Aleister Crowley, and Charles Baudelaire, this sweeping book chronicles evil and the devil in their many forms. --SMS

The Book Against Death by Elias Canetti, tr. Peter Filkins [NF]

In this newly-translated collection, Nobel laureate Canetti, who once called himself death's "mortal enemy," muses on all that death inevitably touches—from the smallest ant to the Greek gods—and condemns death as a byproduct of war and despots' willingness to use death as a pathway to power. By means of this book's very publication, Canetti somewhat succeeds in staving off death himself, ensuring that his words live on forever. —DF

Rise of a Killah by Ghostface Killah [NF]

"Why is the sky blue? Why is water wet? Why did Judas rat to the Romans while Jesus slept?" Ghostface Killah has always asked the big questions. Here's another one: Who needs to read a blurb on a literary site to convince them to read Ghost's memoir? —JHM

May 21

Exhibit by R.O. Kwon [F]

It's been six years since Kwon's debut, The Incendiaries, hit shelves, and based on that book's flinty prose alone, her latest would be worth a read. But it's also a tale of awakening—of its protagonist's latent queerness, and of the "unquiet spirit of an ancestor," that the author herself calls so "shot through with physical longing, queer lust, and kink" that she hopes her parents will never read it. Tantalizing enough for you? —JHM

Cecilia by K-Ming Chang [F]

Chang, the author of Bestiary, Gods of Want, and Organ Meats, returns with this provocative and oft-surreal novella. While the story is about two childhood friends who became estranged after a bizarre sexual encounter but re-connect a decade later, it’s also an exploration of how the human body and its excretions can be both pleasurable and disgusting. —CK

The Great State of West Florida by Kent Wascom [F]

The Great State of West Florida is Wascom's latest gothicomic novel set on Florida's apocalyptic coast. A gritty, ominous book filled with doomed Floridians, the passages fly by with sentences that delight in propulsive excess. In the vein of Thomas McGuane's early novels or Brian De Palma's heyday, this stylized, savory, and witty novel wields pulp with care until it blooms into a new strain of American gothic. —Zachary Issenberg

Cartoons by Kit Schluter [F]

Bursting with Kafkaesque absurdism and a hearty dab of abstraction, Schluter’s Cartoons is an animated vignette of life's minutae. From the ravings of an existential microwave to a pencil that is afraid of paper, Schluter’s episodic outré oozes with animism and uncanniness. A grand addition to City Light’s repertoire, it will serve as a zany reminder of the lengths to which great fiction can stretch. —DF

May 28

Lost Writings by Mina Loy, ed. Karla Kelsey [F]

In the early 20th century, avant-garde author, visual artist, and gallerist Mina Loy (1882–1966) led an astonishing creative life amid European and American modernist circles; she satirized Futurists, participated in Surrealist performance art, and created paintings and assemblages in addition to writing about her experiences in male-dominated fields of artistic practice. Diligent feminist scholars and art historians have long insisted on her cultural significance, yet the first Loy retrospective wasn’t until 2023. Now Karla Kelsey, a poet and essayist, unveils two never-before-published, autobiographical midcentury manuscripts by Loy, The Child and the Parent and Islands in the Air, written from the 1930s to the 1950s. It's never a bad time to be re-rediscovered. —NodB

I'm a Fool to Want You by Camila Sosa Villada, tr. Kit Maude [F]

Villada, whose debut novel Bad Girls, also translated by Maude, captured the travesti experience in Argentina, returns with a short story collection that runs the genre gamut from gritty realism and social satire to science fiction and fantasy. The throughline is Villada's boundless imagination, whether she's conjuring the chaos of the Mexican Inquisition or a trans sex worker befriending a down-and-out Billie Holiday. Angie Cruz calls this "one of my favorite short-story collections of all time." —SMS

The Editor by Sara B. Franklin [NF]

Franklin's tenderly written and meticulously researched biography of Judith Jones—the legendary Knopf editor who worked with such authors as John Updike, Sylvia Plath, Elizabeth Bowen, Anne Tyler, and, perhaps most consequentially, Julia Child—was largely inspired by Franklin's own friendship with Jones in the final years of her life, and draws on a rich trove of interviews and archives. The Editor retrieves Jones from the margins of publishing history and affirms her essential role in shaping the postwar cultural landscape, from fiction to cooking and beyond. —SMS

The Book-Makers by Adam Smyth [NF]

A history of the book told through 18 microbiographies of particularly noteworthy historical personages who made them? If that's not enough to convince you, consider this: the small press is represented here by Nancy Cunard, the punchy and enormously influential founder of Hours Press who romanced both Aldous Huxley and Ezra Pound, knew Hemingway and Joyce and Langston Hughes and William Carlos Williams, and has her own MI5 file. Also, the subject of the binding chapter is named "William Wildgoose." —JHM

June

June 4

The Future Was Color by Patrick Nathan [F]

A gay Hungarian immigrant writing crappy monster movies in the McCarthy-era Hollywood studio system gets swept up by a famous actress and brought to her estate in Malibu to write what he really cares about—and realizes he can never escape his traumatic past. Sunset Boulevard is shaking. —JHM

A Cage Went in Search of a Bird [F]

This collection brings together a who's who of literary writers—10 of them, to be precise— to write Kafka fanfiction, from Joshua Cohen to Yiyun Li. Then it throws in weirdo screenwriting dynamo Charlie Kaufman, for good measure. A boon for Kafkaheads everywhere. —JHM

We Refuse by Kellie Carter Jackson [NF]

Jackson, a historian and professor at Wellesley College, explores the past and present of Black resistance to white supremacy, from work stoppages to armed revolt. Paying special attention to acts of resistance by Black women, Jackson attempts to correct the historical record while plotting a path forward. Jelani Cobb describes this "insurgent history" as "unsparing, erudite, and incisive." —SMS

Holding It Together by Jessica Calarco [NF]

Sociologist Calarco's latest considers how, in lieu of social safety nets, the U.S. has long relied on women's labor, particularly as caregivers, to hold society together. Calarco argues that while other affluent nations cover the costs of care work and direct significant resources toward welfare programs, American women continue to bear the brunt of the unpaid domestic labor that keeps the nation afloat. Anne Helen Petersen calls this "a punch in the gut and a call to action." —SMS

Miss May Does Not Exist by Carrie Courogen [NF]

A biography of Elaine May—what more is there to say? I cannot wait to read this chronicle of May's life, work, and genius by one of my favorite writers and tweeters. Claire Dederer calls this "the biography Elaine May deserves"—which is to say, as brilliant as she was. —SMS

Fire Exit by Morgan Talty [F]

Talty, whose gritty story collection Night of the Living Rez was garlanded with awards, weighs the concept of blood quantum—a measure that federally recognized tribes often use to determine Indigenous membership—in his debut novel. Although Talty is a citizen of the Penobscot Indian Nation, his narrator is on the outside looking in, a working-class white man named Charles who grew up on Maine’s Penobscot Reservation with a Native stepfather and friends. Now Charles, across the river from the reservation and separated from his biological daughter, who lives there, ponders his exclusion in a novel that stokes controversy around the terms of belonging. —NodB

June 11

The Material by Camille Bordas [F]

My high school English teacher, a somewhat dowdy but slyly comical religious brother, had a saying about teaching high school students: "They don't remember the material, but they remember the shtick." Leave it to a well-named novel about stand-up comedy (by the French author of How to Behave in a Crowd) to make you remember both. --SMS

Ask Me Again by Clare Sestanovich [F]

Sestanovich follows up her debut story collection, Objects of Desire, with a novel exploring a complicated friendship over the years. While Eva and Jamie are seemingly opposites—she's a reserved South Brooklynite, while he's a brash Upper Manhattanite—they bond over their innate curiosity. Their paths ultimately diverge when Eva settles into a conventional career as Jamie channels his rebelliousness into politics. Ask Me Again speaks to anyone who has ever wondered whether going against the grain is in itself a matter of privilege. Jenny Offill calls this "a beautifully observed and deeply philosophical novel, which surprises and delights at every turn." —LA

Disordered Attention by Claire Bishop [NF]

Across four essays, art historian and critic Bishop diagnoses how digital technology and the attention economy have changed the way we look at art and performance today, identifying trends across the last three decades. A perfect read for fans of Anna Kornbluh's Immediacy, or the Style of Too Late Capitalism (also from Verso).

War by Louis-Ferdinand Céline, tr. Charlotte Mandell [F]

For years, literary scholars mourned the lost manuscripts of Céline, the acclaimed and reviled French author whose work was stolen from his Paris apartment after he fled to Germany in 1944, fearing punishment for his collaboration with the Nazis. But, with the recent discovery of those fabled manuscripts, War is now seeing the light of day thanks to New Directions (for anglophone readers, at least—the French have enjoyed this one since 2022 courtesy of Gallimard). Adam Gopnik writes of War, "A more intense realization of the horrors of the Great War has never been written." —DF

The Uptown Local by Cory Leadbeater [NF]

In his debut memoir, Leadbeater revisits the decade he spent working as Joan Didion's personal assistant. While he enjoyed the benefits of working with Didion—her friendship and mentorship, the more glamorous appointments on her social calendar—he was also struggling with depression, addiction, and profound loss. Leadbeater chronicles it all in what Chloé Cooper Jones calls "a beautiful catalog of twin yearnings: to be seen and to disappear; to belong everywhere and nowhere; to go forth and to return home, and—above all else—to love and to be loved." —SMS

Out of the Sierra by Victoria Blanco [NF]

Blanco weaves storytelling with old-fashioned investigative journalism to spotlight the endurance of Mexico's Rarámuri people, one of the largest Indigenous tribes in North America, in the face of environmental disasters, poverty, and the attempts to erase their language and culture. This is an important book for our times, dealing with pressing issues such as colonialism, migration, climate change, and the broken justice system. —CK

Any Person Is the Only Self by Elisa Gabbert [NF]

Gabbert is one of my favorite living writers, whether she's deconstructing a poem or tweeting about Seinfeld. Her essays are what I love most, and her newest collection—following 2020's The Unreality of Memory—sees Gabbert in rare form: witty and insightful, clear-eyed and candid. I adored these essays, and I hope (the inevitable success of) this book might augur something an essay-collection renaissance. (Seriously! Publishers! Where are the essay collections!) —SMS

Tehrangeles by Porochista Khakpour [F]

Khakpour's wit has always been keen, and it's hard to imagine a writer better positioned to take the concept of Shahs of Sunset and make it literary. "Like Little Women on an ayahuasca trip," says Kevin Kwan, "Tehrangeles is delightfully twisted and heartfelt." —JHM

Traveling: On the Path of Joni Mitchell by Ann Powers [NF]

The moment I saw this book's title—which comes from the opening (and, as it happens, my favorite) track on Mitchell's 1971 masterpiece Blue—I knew it would be one of my favorite reads of the year. Powers, one of the very best music critics we've got, masterfully guides readers through Mitchell's life and work at a fascinating slant, her approach both sweeping and intimate as she occupies the dual roles of biographer and fan. —SMS

All Desire Is a Desire for Being by René Girard, ed. Cynthia L. Haven [NF]

I'll be honest—the title alone stirs something primal in me. In honor of Girard's centennial, Penguin Classics is releasing a smartly curated collection of his most poignant—and timely—essays, touching on everything from violence to religion to the nature of desire. Comprising essays selected by the scholar and literary critic Cynthia L. Haven, who is also the author of the first-ever biographical study of Girard, Evolution of Desire, this book is "essential reading for Girard devotees and a perfect entrée for newcomers," per Maria Stepanova. —DF

June 18

Craft by Ananda Lima [F]

Can you imagine a situation in which interconnected stories about a writer who sleeps with the devil at a Halloween party and can't shake him over the following decades wouldn't compel? Also, in one of the stories, New York City’s Penn Station is an analogue for hell, which is both funny and accurate. —JHM

Parade by Rachel Cusk [F]

Rachel Cusk has a new novel, her first in three years—the anticipation is self-explanatory. —SMS

Little Rot by Akwaeke Emezi [F]

Multimedia polymath and gender-norm disrupter Emezi, who just dropped an Afropop EP under the name Akwaeke, examines taboo and trauma in their creative work. This literary thriller opens with an upscale sex party and escalating violence, and although pre-pub descriptions leave much to the imagination (promising “the elite underbelly of a Nigerian city” and “a tangled web of sex and lies and corruption”), Emezi can be counted upon for an ambience of dread and a feverish momentum. —NodB

When the Clock Broke by John Ganz [NF]

I was having a conversation with multiple brilliant, thoughtful friends the other day, and none of them remembered the year during which the Battle of Waterloo took place. Which is to say that, as a rule, we should all learn our history better. So it behooves us now to listen to John Ganz when he tells us that all the wackadoodle fascist right-wing nonsense we can't seem to shake from our political system has been kicking around since at least the early 1990s. —JHM

Night Flyer by Tiya Miles [NF]

Miles is one of our greatest living historians and a beautiful writer to boot, as evidenced by her National Book Award–winning book All That She Carried. Her latest is a reckoning with the life and legend of Harriet Tubman, which Miles herself describes as an "impressionistic biography." As in all her work, Miles fleshes out the complexity, humanity, and social and emotional world of her subject. Tubman biographer Catherine Clinton says Miles "continues to captivate readers with her luminous prose, her riveting attention to detail, and her continuing genius to bring the past to life." —SMS

God Bless You, Otis Spunkmeyer by Joseph Earl Thomas [F]

Thomas's debut novel comes just two years after a powerful memoir of growing up Black, gay, nerdy, and in poverty in 1990s Philadelphia. Here, he returns to themes and settings that in that book, Sink, proved devastating, and throws post-service military trauma into the mix. —JHM

June 25

The Garden Against Time by Olivia Laing [NF]

I've been a fan of Laing's since The Lonely City, a formative read for a much-younger me (and I'd suspect for many Millions readers), so I'm looking forward to her latest, an inquiry into paradise refracted through the experience of restoring an 18th-century garden at her home the English countryside. As always, her life becomes a springboard for exploring big, thorny ideas (no pun intended)—in this case, the possibilities of gardens and what it means to make paradise on earth. —SMS

Cue the Sun! by Emily Nussbaum [NF]

Emily Nussbaum is pretty much the reason I started writing. Her 2019 collection of television criticism, I Like to Watch, was something of a Bible for college-aged me (and, in fact, was the first book I ever reviewed), and I've been anxiously awaiting her next book ever since. It's finally arrived, in the form of an utterly devourable cultural history of reality TV. Samantha Irby says, "Only Emily Nussbaum could get me to read, and love, a book about reality TV rather than just watching it," and David Grann remarks, "It’s rare for a book to feel alive, but this one does." —SMS

Woman of Interest by Tracy O'Neill [NF]

O’Neill's first work of nonfiction—an intimate memoir written with the narrative propulsion of a detective novel—finds her on the hunt for her biological mother, who she worries might be dying somewhere in South Korea. As she uncovers the truth about her enigmatic mother with the help of a private investigator, her journey increasingly becomes one of self-discovery. Chloé Cooper Jones writes that Woman of Interest “solidifies her status as one of our greatest living prose stylists.” —LA

Dancing on My Own by Simon Wu [NF]

New Yorkers reading this list may have witnessed Wu's artful curation at the Brooklyn Museum, or the Whitney, or the Museum of Modern Art. It makes one wonder how much he curated the order of these excellent, wide-ranging essays, which meld art criticism, personal narrative, and travel writing—and count Cathy Park Hong and Claudia Rankine as fans. —JHM

[millions_email]

Most Anticipated, Too: The Great Second-Half 2016 Nonfiction Book Preview

Last week, we previewed 93 works of fiction due out in the second half of 2016. Today, we follow up with 44 nonfiction titles coming out in the next six months, ranging from a new rock memoir by Bruce Springsteen to a biography of one our country’s most underrated writers, Shirley Jackson, by critic Ruth Franklin. Along the way, we profile hotly anticipated titles by Jesmyn Ward, Tom Wolfe, Teju Cole, Jennifer Weiner, Michael Lewis, our own Mark O’Connell, and many more.

Break out the beach umbrellas and the sun block. It’s shaping up to be a very hot summer (and fall!) for new nonfiction.

July:

How to Be a Person in the World by Heather Havrilesky: Advice from “Polly,” New York magazine’s online column for the lovelorn, career-confused, adulthood-challenged, and generally angsty. Havrilesky pours her heart into her answers, offering guidance that is equal parts tough love, “I’ve been there,” and curveball. This collection includes new material as well as previously published fan favorites. (Hannah)

Trump: A Graphic Biography by Ted Rall: Just in time for the Republican convention, cartoonist Rall follows his recent graphic bios of Sen. Bernie Sanders and CIA whistleblower Edward Snowden with a comic book peek into the life and times of America’s favorite short-fingered vulgarian. Given that Rall once called on Barack Obama to resign, saying the 44th president made “Bill Clinton look like a paragon of integrity and follow-through,” it’s a safe bet that Trump won’t be flogging this one on his campaign website. (Michael)

Not Pretty Enough by Gerri Hirshey: A biography of Helen Gurley Brown, the founder and creator of Cosmopolitan magazine, following Brown from her upbringing in the Ozarks to her freewheeling single years in L.A. to her rise in the New York advertising and magazine world. The “fun, fearless” editor lived large and worked hard, embracing new sexual and economic freedoms and teaching other women to do the same by offering candid advice on sex, love, money, career, and friendship. (Hannah)

Bush by Jean Edward Smith: He did it his way. According to Smith, author of previous bios of Dwight D. Eisenhower and F.D.R., President George W. Bush relied on his religious faith and gut instinct to make key decisions of his presidency, including the fateful order to invade Iraq a year and a half after the 9/11 attacks. Only in the final months of his second term, with the banking system nearing collapse, did the “Decider-in-Chief” pay closer attention to expert advice and take actions that pulled the world economy back from the brink. (Michael)

Welcome to the Goddamn Ice Cube by Blair Braverman: Fans of This American Life might recognize Braverman from Episode 558, “Game Face”, in which Braverman, working as a dog musher, got stuck in a storm on an Alaskan glacier with a group of tourists who had no idea of the danger they were in. Her memoir describes her tendency to court danger as she ventures into the arctic, a landscape that is not only physically exhausting but also a man’s world that doesn’t have much room for a young woman. (Hannah)

The Voyeur’s Motel by Gay Talese: Some questioned Talese’s journalistic ethics when an excerpt from this book was published in The New Yorker in April. Others admired it as an endurance feat of reporting. Talese spent decades corresponding and visiting a voyeuristic motel owner, Gerald Foos, who constructed a motel that allowed him to secretly spy on his guests. After 35 years, Foos agreed to let Talese reveal his identity and lifelong obsession with voyeurism. In the weeks leading up to publication, Talese has admitted that some of the facts in the book are wrong and told The Washington Post that he won’t be promoting it. Then he told the The New York Times he would be promoting it. We don't know what to make of it all, either. You'll just have to read the book and decide for yourself. (Hannah)

Bobby Kennedy by Larry Tye: Drawing on interviews, unpublished memoirs, newly released government files, “and fifty-eight boxes of papers that had been under lock and key for the past forty years,” Tye traces Bobby Kennedy’s journey from 1950s cold warrior to 1960s liberal icon following the assassination of his older brother, John, in 1963. In an era when presidential candidates are routinely excoriated for decades-old policy positions, it can be instructive to recall that the would-be savior of the urban poor began his public life just 15 years earlier as counsel to red-baiting Sen. Joseph McCarthy. (Michael)

August

The Fire This Time edited by Jesmyn Ward: Fifty-three years after James Baldwin’s classic The Fire Next Time, and one year after Ta-Nehisi Coates’s scalding book-length meditation on race, Between the World and Me, Ward has collected 18 essays by some of the country’s foremost thinkers on race in America, including Claudia Rankine, Isabel Wilkerson, and former U.S. Poet Laureate Natasha Trethewey. “To Baldwin's call we now have a choral response -- one that should be read by every one of us committed to the cause of equality and freedom,” says historian Jelani Cobb.

The Gardener and the Carpenter by Alison Gopnik: This parenting book takes issue with the culture of “parenting,” a hyper-vigilant, goal-oriented style of childcare that leaves children and caregivers exhausted. Gopnik, a developmental psychologist, and the author of The Philosophical Baby, argues that parents should adopt a looser style, one that is more akin to gardening than building a particular structure. Her metaphor is backed up by years of research and observation. (Hannah)

Scream by Tama Janowitz: A memoir from the author of Slaves of New York, the acclaimed short story collection about young people trying to make it in downtown Manhattan in the 1980s. Following the publication of Slaves, Janowitz was grouped with the “Brat Pack” writers Bret Easton Ellis and Jay McInerney famed for their deadpan minimalist style. Scream reflects on that time, as well as the more universal life experiences that followed as Janowitz became a wife, mother, and caregiver to her aging mother. (Hannah)

American Heiress by Jeffrey Toobin: As the author of The Run of His Life, about the O.J. Simpson murder trial, and A Vast Conspiracy, about the Bill Clinton-Monica Lewinsky sex scandal, Toobin is no stranger to tabloid-drenched legal sagas, which makes him an ideal guide to the media circus surrounding Patty Hearst’s 1974 kidnapping and later trial for bank robbery. Drawing on interviews and a trove of previously unreleased records, Toobin, a New Yorker staff writer, tries to make sense of one of the weirdest and most violent episodes in recent American history. (Michael)

The Kingdom of Speech by Tom Wolfe: The maximalist novelist returns to his nonfiction roots with a book that argues speech is what divides humans from animals, above all else. (Tell that to Dr. Dolittle!) Wolfe delves into controversial debates about what role speech has played in our evolution as a technological species. For a sneak preview of his arguments, check out his 2006 NEA lecture, “The Human Beast”. (Hannah)

Blood in the Water by Heather Ann Thompson: Anyone needing to be reminded that the problems in America’s prison system date back to long before the War on Drugs may want to pick up Thompson’s history of the infamous 1971 Attica prison uprising. After 1,300 prisoners seized control of the upstate New York prison, holding guards and other employees hostage for four days, the state sent in troopers to take the prison back by force, leaving 39 people dead and 100 more severely injured. Thompson has drawn on newly unearthed documents and interviews with participants from all sides of the debacle to create what is being billed the “first definitive account” of the uprising 45 years ago. (Michael)

Known and Strange Things by Teju Cole: This first work of nonfiction by the Nigerian-American novelist best known for Open City collects more than 50 short essays touching on topics from Virginia Woolf and William Shakespeare to Instagram and the Black Lives Matter movement. In one essay, Cole, an art historian and photographer, looks at how African-American photographer Roy DeCarava, forced to shoot with film designed for white skin tones, depicted his black subjects. In another essay, Cole dissects “the White Savior Industrial Complex” that he says guides much of Western aid to African nations. (Michael)

September

Born to Run by Bruce Springsteen: After performing at halftime for the 2009 Super Bowl, the bard of New Jersey decided it was time to write his memoirs. This 500-page doorstopper covers Springsteen’s Catholic childhood, his early ambition to become a musician, his inspirations, and the formation of the E Street Band. Springsteen’s lyrics have always shown a gift for storytelling, so we’re guessing this is going to be a good read. (Hannah)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O’Neil: Big Data is everywhere, setting our insurance premiums, evaluating our job performance, and deciding whether we qualify for that special interest rate on our home loan. In theory, this should eliminate bias and make ours a better, fairer world, but in fact, says O’Neil, a former Wall Street data analyst, the algorithms that rule our lives can reinforce discrimination if they’re sloppily designed or improperly applied. O’Neil has a Ph.D. in math from Harvard, and runs the blog, mathbabe.org, where you can find answers to questions like “Why did the Brexit polls get it so wrong?” and why the data-driven policing program “Broken Windows” doesn’t work. (Michael)

Words on the Move by John McWhorter: Does the way some people use the word “literally” drive you up the (metaphorical) wall? Before you, like, blow a gasket, try this book by a Columbia University professor who argues that we should embrace rather than condemn the natural evolution of the English language, whether it’s the use of “literally” to mean “figuratively” or the advent of business jargon like “What’s the ask?” If that’s not enough bracing talk about how we talk, in January 2017 McWhorter is releasing a second book, Talking Back, Talking Black, about African American Vernacular English. (Michael)

The Pigeon Tunnel by John le Carré: The British intelligence officer turned bestselling spy novelist has written his first memoir, regaling readers with stories from his extraordinary writing career. A witness to great historical change in Europe and abroad, le Carré visited Russia before and after the fall of the Berlin Wall, and met many fascinating characters in his travels, including KGB officers, an imprisoned German terrorist, and a female aid worker who was the inspiration for the main character in The Constant Gardner. Le Carré also writes about watching Alec Guinness take on his most famous character, George Smiley. (Hannah)

Avid Reader: A Life by Robert Gottlieb: Legendary editor and dance aficionado Gottlieb has had a career that could fill several memoirs. He began at Simon & Schuster, where he quickly rose to the top, discovering American classics like Catch-22 along the way. He left Simon & Schuster to run Alfred A. Knopf, and later, to succeed William Shawn as editor of The New Yorker. Gottlieb has worked with some of the country’s most celebrated writers, including John Cheever, Toni Morrison, Shirley Jackson, and Robert Caro. (Hannah)

This Vast Southern Empire by Matthew Karp: In the contemporary American mind, the Confederacy is recalled as a rump government of Southern plutocrats bent on protecting an increasingly outmoded form of chattel slavery, but as this new history reminds us, before the Civil War, many of the men who guided America’s foreign policy and territorial expansion were Southern slave owners. At the height of their power in antebellum Washington, Southern politicians like Vice President John C. Calhoun and U.S. Secretary of War Jefferson Davis modernized the U.S. military and protected slavery in Brazil, Cuba, and the Republic of Texas. (Michael)

Shirley Jackson by Ruth Franklin: Shirley Jackson, best known for her bone-chilling and classic short story, “The Lottery,” has to be one of our most underrated novelists. Franklin describes Jackson’s fiction as “domestic horror,” a pioneering genre that explored women’s isolation in marriage and family life through the occult. Franklin’s biography has already been praised by Neil Gaiman, who wrote that it provides “a way of reading Jackson and her work that threads her into the weave of the world of words, as a writer and as a woman, rather than excludes her as an anomaly.” (Hannah)

When in French by Lauren Collins: New Yorker staffer Collins moved to London only to fall in love with a Frenchman. For years, the couple spoke to each another in English but Collins always wondered what she was missing by not communicating in her partner’s native tongue. When she and her husband moved to Geneva, Collins decided to learn French from the Swiss. When in French details Collins’s struggles to learn a new language in her 30s, as well as the joy of attaining a deeper understanding of French culture and people. (Hannah)

Hidden Figures by Margot Lee Shetterly: During the early Space Race years, female mathematicians known as “human computers” used slide rules and adding machines to make the calculations that launched rockets, and later astronauts, into space. Many of these women were black math teachers recruited from segregated schools in the South to fill spots in the aeronautics industry created by wartime labor shortages. Not surprisingly, Hidden Figures, which focuses on the all-black “West Computing” group at the Langley Memorial Aeronautical Laboratory, is being made into a movie starring Taraji Henson and Kevin Costner. (Michael)

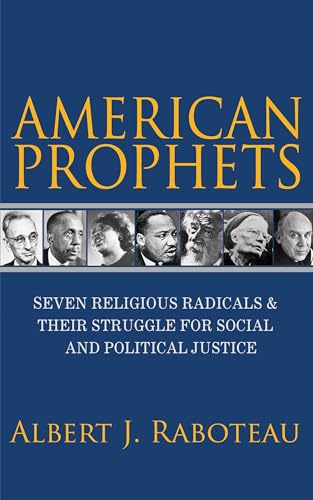

American Prophets by Albert J. Raboteau: This fascinating social history profiles seven religious leaders whose collective efforts helped to fight war, racism, and poverty and bring about massive social change in midcentury America. It’s a list that includes Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., as well as Abraham Joshua Heschel, A. J. Muste, Dorothy Day, Howard Thurman, Thomas Merton, and Fannie Lou Hamer. Raboteau finds new connections between these figures and delves into the ideas and theologies that inspired them. (Hannah)

The Art of Waiting by Belle Boggs: The title of this essay collection comes from Boggs’s much-shared Orion essay, which frankly depicted her despair as she realized that she might never conceive a child. What made the essay special was Boggs’s eye to the natural world, as she observed fertility and birth in the birds and animals near her rural home. Boggs continues to focus her gaze outward in these essays as she reports on families who have chosen to adopt, LBGT couples considering surrogacy and assisted reproduction, and the financial and legal complications accompanying these alternative means of fertility. (Hannah)

Time Travel: A History by James Gleick: The tech-savvy author of The Information and Chaos shows how time travel as a literary conceit is intimately intertwined with the modern understanding of time that arose from technological innovations like the telegraph, train travel, and advances in clock-making. Beginning with H.G. Wells, author of The Time Machine, Gleick tracks the evolution of time travel as a cultural construct from the novels of Marcel Proust to the cult British TV show Doctor Who. (Michael)

Strangers in Their Own Land by Arlie Russell Hochschild: Perfectly timed for the start of the last lap of the presidential campaign, this book endeavors to see red-state voters as they see themselves -- not as dupes of right-wing media, but as ordinary, patriotic Americans trying to do the best for their families and themselves. A renowned sociologist and author of The Second Shift, a classic 1989 study of women’s roles in working families, Hochschild ventures far from her home in uber-liberal Berkeley, Calif., to meet hardcore conservatives in southern Louisiana. There, as in so much of working-class America, she finds lives riven by stagnant wages, the loss of homes, and an exhausting chase after an ever-elusive American dream. (Michael)

Eyes on the Street by Robert Kanigel: Anyone who has window-shopped in SoHo or marveled at the walkability of their neighborhood can thank activist Jane Jacobs who forever changed how planners thought about and designed urban spaces with her landmark 1961 book The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Kanigel, author of The Man Who Knew Infinity, traces the roots of the great urban pioneer who wrote seven books and stopped New York’s all-powerful planning czar Robert Moses from running a major highway through Lower Manhattan, all without a college degree. (Michael)

October

Love for Sale by David Hajdu: In his previous books, Hajdu has written about jazz and folk music; in Love for Sale he tells the story of American popular music from its vaudeville beginnings to Blondie at CBGB to today’s electronic dance music. Hajdu highlights overlooked performers like blues singer Bessie Smith and Jimmie Rodgers, a country singer who incorporated yodeling into his music. (Hannah)

Future Sex by Emily Witt: In her first book, journalist and critic Witt writes about the intersection between sex and technology, otherwise known as online dating. Witt reports on internet pornography, polyamory, and other sexual subcultures, giving an honest and open-minded account of how people pursue pleasure and connection in a changing sexual landscape. (Hannah)

Hungry Heart by Jennifer Weiner: No, it’s not the second volume of Springsteen’s memoirs -- instead, it’s an essay collection from a bestselling author who may be as famous for her defense of chick-lit as she is for her own female-centric novels. This is Weiner’s first volume of nonfiction, and she has a lifetime of topics to cover: growing up as an outsider in her picture-perfect town, her early years as a newspaper reporter, finding her voice as a novelist, becoming a mother, the death of her estranged father, and what it felt like to hear her daughter use the “f-word” -- “fat” -- for the first time. (Hannah)

Truevine by Beth Macy: One day in 1899, a white man offered a piece of candy to George and Willie Muse, the children of black sharecroppers in Truevine, Va., setting off a chain of events that led to the boys being kidnapped into a circus, which billed them as cannibals and “Ambassadors from Mars” in tours that played for royalty at Buckingham Palace and in sold-out shows at Madison Square Garden. Like Macy’s last book, Factory Man, about a good-old-boy owner of a local furniture factory in Virginia who took on low-cost Chinese exporters and won, Truevine promises a mix of quirky characters, propulsive narrative, and an insider’s look at a neglected corner of American history. (Michael)

Upstream by Mary Oliver: Essays from one of America’s most beloved poets. As always, Oliver’s draws inspiration from the natural world, and Provincetown, Mass., her home and life-long muse. Oliver also writes about her early love of Walt Whitman, the labor of poetry, and the continuing influence of classic American writers such as Robert Frost, Edgar Allan Poe, and Ralph Waldo Emerson. (Hannah)

Black Elk by Joe Jackson: A biography of a Native American holy man whose epic life spanned a dramatic era in the history of the American West. In his youth, Black Elk fought in Little Big Horn, witnessed the death of his second cousin, Crazy Horse, and traveled to Europe to perform in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. In later years, he fought in Wounded Knee, became an activist for the Lakota people, and converted to Catholicism. Known to many through his spiritual testimony, Black Elk Speaks, this biography brings the man to life, as well as the turbulent times he lived through. (Hannah)

November

Born a Crime by Trevor Noah: As the child of a white Dutch father and a black Xhosa mother who had to pretend she was her own child’s nanny on the rare occasions the family was together, comedian Noah’s very existence was evidence of a crime under the apartheid laws of his native South Africa. In his memoir, Noah recalls eating caterpillars to stave off hunger and being thrown by his eccentric mother from a speeding car driven by murderous gangsters. If you survived a childhood like that, you might not be so intimated at the prospect of replacing Jon Stewart on The Daily Show, either. (Michael)

My Lost Poets by Philip Levine: In this posthumous essay collection from one of our pre-eminent poets, Levine writes about composing poems as a child, studying with John Berryman, the influence of Spanish poets on his work, his idols and mentors, and his many inspirations: jazz, Spain, Detroit, and masters of the form like William Wordsworth and John Keats. (Hannah)

Writing to Save a Life by John Edgar Wideman: Ten years before Emmett Till was brutally lynched for supposedly whistling at a white woman in Mississippi, his father Louis was executed by the U.S. army for rape and murder. Wideman, who was the same age as Emmett Till, just 14, the year he was murdered, mixes memoir and historical research in his exploration of the eerily twinned executions of the two Till men. A Rhodes Scholar and MacArthur “genius grant” recipient, Wideman knows all too well what it means to have a close relative accused of a violent crime: his son, Jacob, and his brother, Robert, were both convicted of murder. (Michael)

Searching for John Hughes by Jason Diamond: Diamond has established himself as an authority on/gently obsessive superfan of John Hughes with pieces on the filmmaker for Buzzfeed and The Atlantic (from where I learned the shameful fact that John Hughes was responsible for the movie Flubber in addition to his suite of beloved suburban-white-kid films). Diamond’s Hughes interest stretches back to his time as an aspiring, and doomed, Hughes biographer. Diamond commemorates this journey through a memoir and cultural history of a brief, vanished moment in the Chicagoland suburbs. (Lydia)

December

The Undoing Project by Michael Lewis: Why do people go with their guts, even when their guts so often steer them wrong? Lewis stumbled onto this fundamental human question in his bestselling 2003 book Moneyball, about how the Oakland A’s, a cash-strapped major league team, used data analysis to beat wealthier teams. A brief reference in a review of Moneyball in The New Republic led Lewis to two psychologists, Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, whose work explores why humans follow their intuition. If Kahneman’s name sounds familiar, that’s because he’s a Nobel laureate and author of the 2011 bestseller Thinking Fast and Slow. That’s a lot of bestseller cred in one book. (Michael)

And Beyond

To Be a Machine by Mark O’Connell: In his first full-length book, due out in March 2017, longtime Millions staff writer O’Connell offers an inside look at the “transhumanism movement,” the adherents of which hope to one day “solve” the problem of death and use technology to propel human evolution. If O’Connell’s pieces for this site and his ebook, Epic Fail: Bad Art, Viral Fame, and the History of the Worst Thing Ever, published by The Millions in 2013, are any guide, To Be a Machine will be smart and odd and very, very funny. (Michael)

Abandon Me by Melissa Febos: Following on the success of her debut memoir, Whip Smart, about her years as a professional dominatrix and junkie, Febos turns back the clock to examine her relationship with her birth father, whose legacy includes his Native American heritage and a tendency toward addiction. Interwoven with these family investigations is the story of Febos’s passionate long-distance love affair with another woman. Abandon Me is slated for February 2017. (Michael)

Lower Ed by Tressie McMillan Cottom: A much-needed examination of the recent expansion of for-profit universities, which have put millions of young people into serious debt at the beginning of their careers. Cottom links the rise of for-profit universities to rising inequality, drawing on her own experience as an admissions counselor at two for-profit universities, and interviewing students, activists, and senior executives in the industry. (Hannah)

Hunger by Roxane Gay: In our spring nonfiction preview, we looked forward to Gay’s memoir Hunger, which was slated to be published in June 2016, but her publishing date has been pushed back to June 2017. According to reporting from EW, and Gay’s own tweets, the book simply took longer than Gay expected. She also wanted its release to follow a book of short stories, Difficult Women, which will be published in January 2017. (Hannah)

And Now We Have Everything by Meaghan O’Connell: Millions Year in Reading alum and New York magazine’s The Cut columnist O’Connell will bring her signature voice to a collection of essays about motherhood billed as “this generation’s Operating Instructions.” Readers who follow O’Connell’s writing for The Cut or her newsletter look forward to a full volume of her relatable, sometimes mordant, sometimes tender reflections on writing and family life. (Lydia)

The Revolution Has Been Televised: On Big Sports and Big Money

Years ago, I wrote a book about the women’s professional tennis tour. In 1973, the year Billie Jean King beat Bobby Riggs, access to players at most tournaments was easy; few agents or managers walled them off from the press. Coaches? Unheard of. Nutritionists? Please. The very best female tennis pros in the country earned thousands of dollars for winning ($25,000 for the U.S. Open), not millions. To save money, they overnighted at the homes of local enthusiasts.

Now, like other sports, tennis is a billion-dollar enterprise and players like Roger Federer and Maria Sharapova rank high on Forbes “Richest Athletes” list. The inflation is just as obvious in my other favorite sport, baseball. A recent Wall Street Journal article on New York Mets pitcher Jacob deGrom, whose 2016 salary is $607,000, carried the headline “Baseball’s Underpaid All-Stars.” The average baseball salary this year is $4.4 million.

Mark McCormack, the agent and lawyer who made Arnold Palmer golf’s first millionaire, and Marvin Miller, the undaunted leader of the baseball players’ union, are among those generally credited as important nonplayers who helped turn sports into a business that benefited its “workers” as well as their employers. There are numerous others, though, and in his new book, Players, Journal reporter Matthew Futterman thoroughly investigates the financial revolution in pro sports. He describes how athletes like hurdler Edwin Moses, unheralded executives like the NFL’s Frank Vuono, and people like McCormack enabled players grab the power that once was in the hands of team owners and event promoters. The revolution, argues Futterman, has in many ways improved the sports that fans love to watch; well-played players who no longer need to work at other jobs in their free hours are better trained, better conditioned (and yes, better compensated). But has the revolution gone overboard?

Players might be the best book about the business of sports since Moneyball. Instead of investigating one sport through the lens of one team, Futterman looks at several major sports, focusing on key participants. He begins with McCormack, whose story has been told before but is still the spark that gave rise to the revolution. McCormack’s guiding principle was that “stars were the gasoline that made the engine of any sport go...They were a salable commodity that was being undervalued...” As a youngster growing up in Chicago in the 1930s and '40s, he loved sports and even when “alone on his porch throwing a ball in the air all afternoon, he was always keeping score.” He became a lawyer and an excellent amateur golfer.

Arnold Palmer was a great golfer. But his earnings were tiny. His big paycheck came from an endorsement deal in 1954 with Wilson for $5,000, yet their clubs were not even premium products; Palmer crafted his own clubs in his home workshop. Moreover the company had the right to renew the deal each time it was about to expire. After convincing Palmer he could do better, McCormack became the golfer’s agent and finally extricated him from the Wilson deal, setting up instead Palmer’s own golf club company. “McCormack was playing a new game,” writes Futterman. “The object was liberation.” His plan to give Palmer control of his own name and marketplace worth would be the template for every other arrangement McCormack made.

McCormack moved on to tennis. After meeting the chairman of Wimbledon, he realized the most prestigious tournament in the world was not taking advantage of its image, and arranged to market the film rights to the tournament. Eventually came the windfall -- a six year deal with NBC for Wimbledon TV for $5.2 million. It was, writes Futterman, a key element in his vision -- to widen the popularity of his players, he needed to showcase them on a mass scale. TV would grow the prize money and thus the value of players’ names to sponsors. McCormack, like Hollywood czar Lew Wasserman, would control not just the stars but the venues. “Wimbledon doesn’t break a leg, sprain an ankle, fail a drug test or lose six-love, six-love,” he told others.

By the 1990s, McCormack’s influence was so pervasive that his company, International Management Company, or IMG, was referred to by nasty nicknames: “I Am Greedy,” “I Manage God.” By 2001 his management roster went well beyond sports -- its list included Margaret Thatcher and the Nobel Prize Foundation.

Every sport had its own path to big money and professionalization. Before 1968, writes Futterman, the men who ran tennis “starved the sport.” Stars who went out on their own, like Rod Laver, barnstormed for peanuts on a pro tour while being barred from the top tournaments like Wimbledon, which was open only to amateurs. Although they were allowed to participate in the Grand Slams after 1968, the International Lawn Tennis Association raked in money while offering poor purses and no say to the players who made it great. This led the men, who had joined together in the Association of Tennis Professionals, to stage a boycott of the 1973 Wimbledon event. It severely hurt the career of American Stan Smith, the defending champion, who honored the boycott. Ultimately, the tennis lords caved, and Smith eventually got his measure of fame by having his name on a best-selling shoe.

The boycott was incredibly successful; it led to a boom as the sport was taken up by recreational players and pros reaped the rewards of wider exposure. The total prize money at the U.S. open was $160,000 in 1972. By 1983 it was $2 million. The growth meant the explosion in the care and nurturing of stars who hired coaches, physiotherapists, and nutritionists, and companies that produced new racquets made of space-age materials. By last year, the male and female U.S. Open winners alone earned over $3 million each.

Baseball, the professional sport most dominant in the first half of the 20th century, saw a similar upward dollar trajectory. Here, Futterman uses pitcher Jim “Catfish” Hunter to tell the story of free agency and the resulting monetary explosion. His career showed how an athlete from a poor farming family in North Carolina upended “the entire salary structure of sports,” showing every “athlete a better lesson in free-market economics than anyone could have gotten at Harvard Business School.” The lesson: “the person who gets paid the most sets the market for everyone else below him,” i.e. a rising tide lifts all boats. How big a lesson was this? In 1966, despite having its own union headed by Miller, baseball’s reserve clause that bound a player to one team meant that the average major league player’s salary was $14,000. Topps paid each exactly $125 to put them on a bubble-gum card.

I’m sorry Futterman did not mention the two-man holdout by the Dodgers’ great pitchers Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale before the 1966 season, when the two asked for a million dollars over three years and settled for about $130,000 for Koufax (in what became his final season) and $105,000 for Drysdale. It was a landmark in the struggle for free agency, which culminated in Hunter’s battle with the “perhaps the greediest and most penurious” ballclub owner, Charles O. Finley of the Oakland A’s.

Players details the almost unbelievable tale of how Finley’s stupid missteps allowed the owner to be declared in default of his contract with Hunter. (Among other things, Finley claimed it was awkward for him to get his estranged wife’s signature on a document.) The pitcher was declared a free agent, an open market bidding war began, and the Yankees signed Hunter to a multimillion dollar contract “worth roughly fifteen times more than the next highest player.” The rest is, well history, right up to Jacob deGrom’s measly $607,000 salary, which is so low because with only three years in the big leagues he is not yet eligible for free agency.

In football, Players dates the revolution not to Commissioner Pete Rozelle, who is often hailed for dragging the NFL into modern times, but to the league’s actions in 1978, when it adopted rules that made offenses more potent. The owners were persuaded by Tex Schramm, general manager of the Dallas Cowboys that unless the game permitted higher scores, it would stagnate. Indeed, once rules limiting defenses in hampering receivers and offensive linemen, and once the “west coast offense” gave quarterbacks a chance to move the ball with lots of short, high percentage passes, it was, in Futterman’s words, “easier for players to thrill fans.”

The star system took hold. In 1990, the league created the Quarterbacks Club, to which the likes of Troy Aikman and Dan Marino lent their names to lucrative licensing arrangements. Where NFL players lost was that, previously, their union had handled the licensing. The new arrangement bled the union dry. Today, football generals get huge salaries but the privates get nonguaranteed contracts.