Mentioned in:

Most Anticipated: The Great Spring 2024 Preview

April

April 2

Women! In! Peril! by Jessie Ren Marshall [F]

For starters, excellent title. This debut short story collection from playwright Marshall spans sex bots and space colonists, wives and divorcées, prodding at the many meanings of womanhood. Short story master Deesha Philyaw, also taken by the book's title, calls this one "incisive! Provocative! And utterly satisfying!" —Sophia M. Stewart

The Audacity by Ryan Chapman [F]

This sophomore effort, after the darkly sublime absurdity of Riots I have Known, trades in the prison industrial complex for the Silicon Valley scam. Chapman has a sharp eye and a sharper wit, and a book billed as a "bracing satire about the implosion of a Theranos-like company, a collapsing marriage, and a billionaires’ 'philanthropy summit'" promises some good, hard laughs—however bitter they may be—at the expense of the über-rich. —John H. Maher

The Obscene Bird of Night by José Donoso, tr. Leonard Mades [F]

I first learned about this book from an essay in this publication by Zachary Issenberg, who alternatively calls it Donoso's "masterpiece," "a perfect novel," and "the crowning achievement of the gothic horror genre." He recommends going into the book without knowing too much, but describes it as "a story assembled from the gossip of society’s highs and lows, which revolves and blurs into a series of interlinked nightmares in which people lose their memory, their sex, or even their literal organs." —SMS

Globetrotting ed. Duncan Minshull [NF]

I'm a big walker, so I won't be able to resist this assemblage of 50 writers—including Edith Wharton, Katharine Mansfield, Helen Garner, and D.H. Lawrence—recounting their various journeys by foot, edited by Minshull, the noted walker-writer-anthologist behind The Vintage Book of Walking (2000) and Where My Feet Fall (2022). —SMS

All Things Are Too Small by Becca Rothfeld [NF]

Hieronymus Bosch, eat your heart out! The debut book from Rothfeld, nonfiction book critic at the Washington Post, celebrates our appetite for excess in all its material, erotic, and gluttonous glory. Covering such disparate subjects from decluttering to David Cronenberg, Rothfeld looks at the dire cultural—and personal—consequences that come with adopting a minimalist sensibility and denying ourselves pleasure. —Daniella Fishman

A Good Happy Girl by Marissa Higgins [F]

Higgins, a regular contributor here at The Millions, debuts with a novel of a young woman who is drawn into an intense and all-consuming emotional and sexual relationship with a married lesbian couple. Halle Butler heaps on the praise for this one: “Sometimes I could not believe how easily this book moved from gross-out sadism into genuine sympathy. Totally surprising, totally compelling. I loved it.” —SMS

City Limits by Megan Kimble [NF]

As a Los Angeleno who is steadily working my way through The Power Broker, this in-depth investigation into the nation's freeways really calls to me. (Did you know Robert Moses couldn't drive?) Kimble channels Caro by locating the human drama behind freeways and failures of urban planning. —SMS

We Loved It All by Lydia Millet [NF]

Planet Earth is a pretty awesome place to be a human, with its beaches and mountains, sunsets and birdsong, creatures great and small. Millet, a creative director at the Center for Biological Diversity in Tucson, infuses her novels with climate grief and cautions against extinction, and in this nonfiction meditation, she makes a case for a more harmonious coexistence between our species and everybody else in the natural world. If a nostalgic note of “Auld Lang Syne” trembles in Millet’s title, her personal anecdotes and public examples call for meaningful environmental action from local to global levels. —Nathalie op de Beeck

Like Love by Maggie Nelson [NF]

The new book from Nelson, one of the most towering public intellectuals alive today, collects 20 years of her work—including essays, profiles, and reviews—that cover disparate subjects, from Prince and Kara Walker to motherhood and queerness. For my fellow Bluets heads, this will be essential reading. —SMS

Traces of Enayat by Iman Mersal, tr. Robin Moger [NF]

Mersal, one of the preeminent poets of the Arabic-speaking world, recovers the life, work, and legacy of the late Egyptian writer Enayat al-Zayyat in this biographical detective story. Mapping the psyche of al-Zayyat, who died by suicide in 1963, alongside her own, Mersal blends literary mystery and memoir to produce a wholly original portrait of two women writers. —SMS

The Letters of Emily Dickinson ed. Cristanne Miller and Domhnall Mitchell [NF]

The letters of Emily Dickinson, one of the greatest and most beguiling of American poets, are collected here for the first time in nearly 60 years. Her correspondence not only gives access to her inner life and social world, but reveal her to be quite the prose stylist. "In these letters," says Jericho Brown, "we see the life of a genius unfold." Essential reading for any Dickinson fan. —SMS

April 9

Short War by Lily Meyer [F]

The debut novel from Meyer, a critic and translator, reckons with the United States' political intervention in South America through the stories of two generations: a young couple who meet in 1970s Santiago, and their American-born child spending a semester Buenos Aires. Meyer is a sharp writer and thinker, and a great translator from the Spanish; I'm looking forward to her fiction debut. —SMS

There's Going to Be Trouble by Jen Silverman [F]

Silverman's third novel spins a tale of an American woman named Minnow who is drawn into a love affair with a radical French activist—a romance that, unbeknown to her, mirrors a relationship her own draft-dodging father had against the backdrop of the student movements of the 1960s. Teasing out the intersections of passion and politics, There's Going to Be Trouble is "juicy and spirited" and "crackling with excitement," per Jami Attenberg. —SMS

Table for One by Yun Ko-eun, tr. Lizzie Buehler [F]

I thoroughly enjoyed Yun Ko-eun's 2020 eco-thriller The Disaster Tourist, also translated by Buehler, so I'm excited for her new story collection, which promises her characteristic blend of mundanity and surrealism, all in the name of probing—and poking fun—at the isolation and inanity of modern urban life. —SMS

Playboy by Constance Debré, tr. Holly James [NF]

The prequel to the much-lauded Love Me Tender, and the first volume in Debré's autobiographical trilogy, Playboy's incisive vignettes explore the author's decision to abandon her marriage and career and pursue the precarious life of a writer, which she once told Chris Kraus was "a bit like Saint Augustine and his conversion." Virginie Despentes is a fan, so I'll be checking this out. —SMS

Native Nations by Kathleen DuVal [NF]

DuVal's sweeping history of Indigenous North America spans a millennium, beginning with the ancient cities that once covered the continent and ending with Native Americans' continued fight for sovereignty. A study of power, violence, and self-governance, Native Nations is an exciting contribution to a new canon of North American history from an Indigenous perspective, perfect for fans of Ned Blackhawk's The Rediscovery of America. —SMS

Personal Score by Ellen van Neerven [NF]

I’ve always been interested in books that drill down on a specific topic in such a way that we also learn something unexpected about the world around us. Australian writer Van Neerven's sports memoir is so much more than that, as they explore the relationship between sports and race, gender, and sexuality—as well as the paradox of playing a colonialist sport on Indigenous lands. Two Dollar Radio, which is renowned for its edgy list, is publishing this book, so I know it’s going to blow my mind. —Claire Kirch

April 16

The Notebooks of Sonny Rollins by Sonny Rollins [NF]

The musings, recollections, and drawings of jazz legend Sonny Rollins are collected in this compilation of his precious notebooks, which he began keeping in 1959, the start of what would become known as his “Bridge Years,” during which he would practice at all hours on the Williamsburg Bridge. Rollins chronicles everything from his daily routine to reflections on music theory and the philosophical underpinnings of his artistry. An indispensable look into the mind and interior life of one of the most celebrated jazz musicians of all time. —DF

Henry Henry by Allen Bratton [F]

Bratton’s ambitious debut reboots Shakespeare’s Henriad, landing Hal Lancaster, who’s in line to be the 17th Duke of Lancaster, in the alcohol-fueled queer party scene of 2014 London. Hal’s identity as a gay man complicates his aristocratic lineage, and his dalliances with over-the-hill actor Jack Falstaff and promising romance with one Harry Percy, who shares a name with history’s Hotspur, will have English majors keeping score. Don’t expect a rom-com, though. Hal’s fraught relationship with his sexually abusive father, and the fates of two previous gay men from the House of Lancaster, lend gravity to this Bard-inspired take. —NodB

Bitter Water Opera by Nicolette Polek [F]

Graywolf always publishes books that make me gasp in awe and this debut novel, by the author of the entrancing 2020 story collection Imaginary Museums, sounds like it’s going to keep me awake at night as well. It’s a tale about a young woman who’s lost her way and writes a letter to a long-dead ballet dancer—who then visits her, and sets off a string of strange occurrences. —CK

Norma by Sarah Mintz [F]

Mintz's debut novel follows the titular widow as she enjoys her newfound freedom by diving headfirst into her surrounds, both IRL and online. Justin Taylor says, "Three days ago I didn’t know Sarah Mintz existed; now I want to know where the hell she’s been all my reading life. (Canada, apparently.)" —SMS

What Kingdom by Fine Gråbøl, tr. Martin Aitken [F]

A woman in a psychiatric ward dreams of "furniture flickering to life," a "chair that greets you," a "bookshelf that can be thrown on like an apron." This sounds like the moving answer to the otherwise puzzling question, "What if the Kantian concept of ding an sich were a novel?" —JHM

Weird Black Girls by Elwin Cotman [F]

Cotman, the author of three prior collections of speculative short stories, mines the anxieties of Black life across these seven tales, each of them packed with pop culture references and supernatural conceits. Kelly Link calls Cotman's writing "a tonic to ward off drabness and despair." —SMS

Presence by Tracy Cochran [NF]

Last year marked my first earnest attempt at learning to live more mindfully in my day-to-day, so I was thrilled when this book serendipitously found its way into my hands. Cochran, a New York-based meditation teacher and Tibetan Buddhist practitioner of 50 years, delivers 20 psycho-biographical chapters on recognizing the importance of the present, no matter how mundane, frustrating, or fortuitous—because ultimately, she says, the present is all we have. —DF

Committed by Suzanne Scanlon [NF]

Scanlon's memoir uses her own experience of mental illness to explore the enduring trope of the "madwoman," mining the work of Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Virginia Woolf, Sylvia Plath, Audre Lorde, and others for insights into the long literary tradition of women in psychological distress. The blurbers for this one immediately caught my eye, among them Natasha Trethewey, Amina Cain, and Clancy Martin, who compares Scanlon's work here to that of Marguerite Duras. —SMS

Unrooted by Erin Zimmerman [NF]

This science memoir explores Zimmerman's journey to botany, a now endangered field. Interwoven with Zimmerman's experiences as a student and a mother is an impassioned argument for botany's continued relevance and importance against the backdrop of climate change—a perfect read for gardeners, plant lovers, or anyone with an affinity for the natural world. —SMS

April 23

Reboot by Justin Taylor [F]

Extremely online novels, as a rule, have become tiresome. But Taylor has long had a keen eye for subcultural quirks, so it's no surprise that PW's Alan Scherstuhl says that "reading it actually feels like tapping into the internet’s best celeb gossip, fiercest fandom outrages, and wildest conspiratorial rabbit holes." If that's not a recommendation for the Book Twitter–brained reader in you, what is? —JHM

Divided Island by Daniela Tarazona, tr. Lizzie Davis and Kevin Gerry Dunn [F]

A story of multiple personalities and grief in fragments would be an easy sell even without this nod from Álvaro Enrigue: "I don't think that there is now, in Mexico, a literary mind more original than Daniela Tarazona's." More original than Mario Bellatin, or Cristina Rivera Garza? This we've gotta see. —JHM

Prairie, Dresses, Art, Other by Danielle Dutton [NF]

Coffee House Press has for years relished its reputation for publishing “experimental” literature, and this collection of short stories and essays about literature and art and the strangeness of our world is right up there with the rest of Coffee House’s edgiest releases. Don’t be fooled by the simple cover art—Dutton’s work is always formally inventive, refreshingly ambitious, and totally brilliant. —CK

I Just Keep Talking by Nell Irvin Painter [NF]

I first encountered Nell Irvin Painter in graduate school, as I hung out with some Americanists who were her students. Painter was always a dazzling, larger-than-life figure, who just exuded power and brilliance. I am so excited to read this collection of her essays on history, literature, and politics, and how they all intersect. The fact that this collection contains Painter’s artwork is a big bonus. —CK

April 30

Real Americans by Rachel Khong [F]

The latest novel from Khong, the author of Goodbye, Vitamin, explores class dynamics and the illusory American Dream across generations. It starts out with a love affair between an impoverished Chinese American woman from an immigrant family and an East Coast elite from a wealthy family, before moving us along 21 years: 15-year-old Nick knows that his single mother is hiding something that has to do with his biological father and thus, his identity. C Pam Zhang deems this "a book of rare charm," and Andrew Sean Greer calls it "gorgeous, heartfelt, soaring, philosophical and deft." —CK

The Swans of Harlem by Karen Valby [NF]

Huge thanks to Bebe Neuwirth for putting this book on my radar (she calls it "fantastic") with additional gratitude to Margo Jefferson for sealing the deal (she calls it "riveting"). Valby's group biography of five Black ballerinas who forever transformed the art form at the height of the Civil Rights movement uncovers the rich and hidden history of Black ballet, spotlighting the trailblazers who paved the way for the Misty Copelands of the world. —SMS

Appreciation Post by Tara Ward [NF]

Art historian Ward writes toward an art history of Instagram in Appreciation Post, which posits that the app has profoundly shifted our long-established ways of interacting with images. Packed with cultural critique and close reading, the book synthesizes art history, gender studies, and media studies to illuminate the outsize role that images play in all of our lives. —SMS

May

May 7

Bad Seed by Gabriel Carle, tr. Heather Houde [F]

Carle’s English-language debut contains echoes of Denis Johnson’s Jesus’s Son and Mariana Enriquez’s gritty short fiction. This story collection haunting but cheeky, grim but hopeful: a student with HIV tries to avoid temptation while working at a bathhouse; an inebriated friend group witnesses San Juan go up in literal flames; a sexually unfulfilled teen drowns out their impulses by binging TV shows. Puerto Rican writer Luis Negrón calls this “an extraordinary literary debut.” —Liv Albright

The Lady Waiting by Magdalena Zyzak [F]

Zyzak’s sophomore novel is a nail-biting delight. When Viva, a young Polish émigré, has a chance encounter with an enigmatic gallerist named Bobby, Viva’s life takes a cinematic turn. Turns out, Bobby and her husband have a hidden agenda—they plan to steal a Vermeer, with Viva as their accomplice. Further complicating things is the inevitable love triangle that develops among them. Victor LaValle calls this “a superb accomplishment," and Percival Everett says, "This novel pops—cosmopolitan, sexy, and funny." —LA

América del Norte by Nicolás Medina Mora [F]

Pitched as a novel that "blends the Latin American traditions of Roberto Bolaño and Fernanda Melchor with the autofiction of U.S. writers like Ben Lerner and Teju Cole," Mora's debut follows a young member of the Mexican elite as he wrestles with questions of race, politics, geography, and immigration. n+1 co-editor Marco Roth calls Mora "the voice of the NAFTA generation, and much more." —SMS

How It Works Out by Myriam Lacroix [F]

LaCroix's debut novel is the latest in a strong early slate of novels for the Overlook Press in 2024, and follows a lesbian couple as their relationship falls to pieces across a number of possible realities. The increasingly fascinating and troubling potentialities—B-list feminist celebrity, toxic employer-employee tryst, adopting a street urchin, cannibalism as relationship cure—form a compelling image of a complex relationship in multiversal hypotheticals. —JHM

Cinema Love by Jiaming Tang [F]

Ting's debut novel, which spans two continents and three timelines, follows two gay men in rural China—and, later, New York City's Chinatown—who frequent the Workers' Cinema, a movie theater where queer men cruise for love. Robert Jones, Jr. praises this one as "the unforgettable work of a patient master," and Jessamine Chan calls it "not just an extraordinary debut, but a future classic." —SMS

First Love by Lilly Dancyger [NF]

Dancyger's essay collection explores the platonic romances that bloom between female friends, giving those bonds the love-story treatment they deserve. Centering each essay around a formative female friendship, and drawing on everything from Anaïs Nin and Sylvia Plath to the "sad girls" of Tumblr, Dancyger probes the myriad meanings and iterations of friendship, love, and womanhood. —SMS

See Loss See Also Love by Yukiko Tominaga [F]

In this impassioned debut, we follow Kyoko, freshly widowed and left to raise her son alone. Through four vignettes, Kyoko must decide how to raise her multiracial son, whether to remarry or stay husbandless, and how to deal with life in the face of loss. Weike Wang describes this one as “imbued with a wealth of wisdom, exploring the languages of love and family.” —DF

The Novices of Lerna by Ángel Bonomini, tr. Jordan Landsman [F]

The Novices of Lerna is Landsman's translation debut, and what a way to start out: with a work by an Argentine writer in the tradition of Jorge Luis Borges and Adolfo Bioy Casares whose work has never been translated into English. Judging by the opening of this short story, also translated by Landsman, Bonomini's novel of a mysterious fellowship at a Swiss university populated by doppelgängers of the protagonist is unlikely to disappoint. —JHM

Black Meme by Legacy Russell [NF]

Russell, best known for her hit manifesto Glitch Feminism, maps Black visual culture in her latest. Black Meme traces the history of Black imagery from 1900 to the present, from the photograph of Emmett Till published in JET magazine to the footage of Rodney King's beating at the hands of the LAPD, which Russell calls the first viral video. Per Margo Jefferson, "You will be galvanized by Legacy Russell’s analytic brilliance and visceral eloquence." —SMS

The Eighth Moon by Jennifer Kabat [NF]

Kabat's debut memoir unearths the history of the small Catskills town to which she relocated in 2005. The site of a 19th-century rural populist uprising, and now home to a colorful cast of characters, the Appalachian community becomes a lens through which Kabat explores political, economic, and ecological issues, mining the archives and the work of such writers as Adrienne Rich and Elizabeth Hardwick along the way. —SMS

Stories from the Center of the World ed. Jordan Elgrably [F]

Many in America hold onto broad, centuries-old misunderstandings of Arab and Muslim life and politics that continue to harm, through both policy and rhetoric, a perpetually embattled and endangered region. With luck, these 25 tales by writers of Middle Eastern and North African origin might open hearts and minds alike. —JHM

An Encyclopedia of Gardening for Colored Children by Jamaica Kincaid and Kara Walker [NF]

Two of the most brilliant minds on the planet—writer Jamaica Kincaid and visual artist Kara Walker—have teamed up! On a book! About plants! A dream come true. Details on this slim volume are scant—see for yourself—but I'm counting down the minutes till I can read it all the same. —SMS

Physics of Sorrow by Georgi Gospodinov, tr. Angela Rodel [F]

I'll be honest: I would pick up this book—by the International Booker Prize–winning author of Time Shelter—for the title alone. But also, the book is billed as a deeply personal meditation on both Communist Bulgaria and Greek myth, so—yep, still picking this one up. —JHM

May 14

This Strange Eventful History by Claire Messud [F]

I read an ARC of this enthralling fictionalization of Messud’s family history—people wandering the world during much of the 20th century, moving from Algeria to France to North America— and it is quite the story, with a postscript that will smack you on the side of the head and make you re-think everything you just read. I can't recommend this enough. —CK

Woodworm by Layla Martinez, tr. Sophie Hughes and Annie McDermott [F]

Martinez’s debut novel takes cabin fever to the max in this story of a grandmother, granddaughter, and their haunted house, set against the backdrop of the Spanish Civil War. As the story unfolds, so do the house’s secrets, the two women must learn to collaborate with the malevolent spirits living among them. Mariana Enriquez says that this "tense, chilling novel tells a story of specters, class war, violence, and loneliness, as naturally as if the witches had dictated this lucid, terrible nightmare to Martínez themselves.” —LA

Self Esteem and the End of the World by Luke Healy [NF]

Ah, writers writing about writing. A tale as old as time, and often timeworn to boot. But graphic novelists graphically noveling about graphic novels? (Verbing weirds language.) It still feels fresh to me! Enter Healy's tale of "two decades of tragicomic self-discovery" following a protagonist "two years post publication of his latest book" and "grappling with his identity as the world crumbles." —JHM

All Fours by Miranda July [F]

In excruciating, hilarious detail, All Fours voices the ethically dubious thoughts and deeds of an unnamed 45-year-old artist who’s worried about aging and her capacity for desire. After setting off on a two-week round-trip drive from Los Angeles to New York City, the narrator impulsively checks into a motel 30 miles from her home and only pretends to be traveling. Her flagrant lies, unapologetic indolence, and semi-consummated seduction of a rent-a-car employee set the stage for a liberatory inquisition of heteronorms and queerness. July taps into the perimenopause zeitgeist that animates Jen Beagin’s Big Swiss and Melissa Broder’s Death Valley. —NodB

Love Junkie by Robert Plunket [F]

When a picture-perfect suburban housewife's life is turned upside down, a chance brush with New York City's gay scene launches her into gainful, albeit unconventional, employment. Set at the dawn of the AIDs epidemic, Mimi Smithers, described as a "modern-day Madame Bovary," goes from planning parties in Westchester to selling used underwear with a Manhattan porn star. As beloved as it is controversial, Plunket's 1992 cult novel will get a much-deserved second life thanks to this reissue by New Directions. (Maybe this will finally galvanize Madonna, who once optioned the film rights, to finally make that movie.) —DF

Tomorrowing by Terry Bisson [F]

The newest volume in Duke University’s Practices series collects for the first time the late Terry Bisson’s Locus column "This Month in History," which ran for two decades. In it, the iconic "They’re Made Out of Meat" author weaves an alt-history of a world almost parallel to ours, featuring AI presidents, moon mountain hikes, a 196-year-old Walt Disney’s resurrection, and a space pooch on Mars. This one promises to be a pure spectacle of speculative fiction. —DF

Chop Fry Watch Learn by Michelle T. King [NF]

A large portion of the American populace still confuses Chinese American food with Chinese food. What a delight, then, to discover this culinary history of the worldwide dissemination of that great cuisine—which moonlights as a biography of Chinese cookbook and TV cooking program pioneer Fu Pei-mei. —JHM

On the Couch ed. Andrew Blauner [NF]

André Aciman, Susie Boyt, Siri Hustvedt, Rivka Galchen, and Colm Tóibín are among the 25 literary luminaries to contribute essays on Freud and his complicated legacy to this lively volume, edited by writer, editor, and literary agent Blauner. Taking tacts both personal and psychoanalytical, these essays paint a fresh, full picture of Freud's life, work, and indelible cultural impact. —SMS

Another Word for Love by Carvell Wallace [NF]

Wallace is one of the best journalists (and tweeters) working today, so I'm really looking forward to his debut memoir, which chronicles growing up Black and queer in America, and navigating the world through adulthood. One of the best writers working today, Kiese Laymon, calls Another Word for Love as “One of the most soulfully crafted memoirs I’ve ever read. I couldn’t figure out how Carvell Wallace blurred time, region, care, and sexuality into something so different from anything I’ve read before." —SMS

The Devil's Best Trick by Randall Sullivan [NF]

A cultural history interspersed with memoir and reportage, Sullivan's latest explores our ever-changing understandings of evil and the devil, from Egyptian gods and the Book of Job to the Salem witch trials and Black Mass ceremonies. Mining the work of everyone from Zoraster, Plato, and John Milton to Edgar Allen Poe, Aleister Crowley, and Charles Baudelaire, this sweeping book chronicles evil and the devil in their many forms. --SMS

The Book Against Death by Elias Canetti, tr. Peter Filkins [NF]

In this newly-translated collection, Nobel laureate Canetti, who once called himself death's "mortal enemy," muses on all that death inevitably touches—from the smallest ant to the Greek gods—and condemns death as a byproduct of war and despots' willingness to use death as a pathway to power. By means of this book's very publication, Canetti somewhat succeeds in staving off death himself, ensuring that his words live on forever. —DF

Rise of a Killah by Ghostface Killah [NF]

"Why is the sky blue? Why is water wet? Why did Judas rat to the Romans while Jesus slept?" Ghostface Killah has always asked the big questions. Here's another one: Who needs to read a blurb on a literary site to convince them to read Ghost's memoir? —JHM

May 21

Exhibit by R.O. Kwon [F]

It's been six years since Kwon's debut, The Incendiaries, hit shelves, and based on that book's flinty prose alone, her latest would be worth a read. But it's also a tale of awakening—of its protagonist's latent queerness, and of the "unquiet spirit of an ancestor," that the author herself calls so "shot through with physical longing, queer lust, and kink" that she hopes her parents will never read it. Tantalizing enough for you? —JHM

Cecilia by K-Ming Chang [F]

Chang, the author of Bestiary, Gods of Want, and Organ Meats, returns with this provocative and oft-surreal novella. While the story is about two childhood friends who became estranged after a bizarre sexual encounter but re-connect a decade later, it’s also an exploration of how the human body and its excretions can be both pleasurable and disgusting. —CK

The Great State of West Florida by Kent Wascom [F]

The Great State of West Florida is Wascom's latest gothicomic novel set on Florida's apocalyptic coast. A gritty, ominous book filled with doomed Floridians, the passages fly by with sentences that delight in propulsive excess. In the vein of Thomas McGuane's early novels or Brian De Palma's heyday, this stylized, savory, and witty novel wields pulp with care until it blooms into a new strain of American gothic. —Zachary Issenberg

Cartoons by Kit Schluter [F]

Bursting with Kafkaesque absurdism and a hearty dab of abstraction, Schluter’s Cartoons is an animated vignette of life's minutae. From the ravings of an existential microwave to a pencil that is afraid of paper, Schluter’s episodic outré oozes with animism and uncanniness. A grand addition to City Light’s repertoire, it will serve as a zany reminder of the lengths to which great fiction can stretch. —DF

May 28

Lost Writings by Mina Loy, ed. Karla Kelsey [F]

In the early 20th century, avant-garde author, visual artist, and gallerist Mina Loy (1882–1966) led an astonishing creative life amid European and American modernist circles; she satirized Futurists, participated in Surrealist performance art, and created paintings and assemblages in addition to writing about her experiences in male-dominated fields of artistic practice. Diligent feminist scholars and art historians have long insisted on her cultural significance, yet the first Loy retrospective wasn’t until 2023. Now Karla Kelsey, a poet and essayist, unveils two never-before-published, autobiographical midcentury manuscripts by Loy, The Child and the Parent and Islands in the Air, written from the 1930s to the 1950s. It's never a bad time to be re-rediscovered. —NodB

I'm a Fool to Want You by Camila Sosa Villada, tr. Kit Maude [F]

Villada, whose debut novel Bad Girls, also translated by Maude, captured the travesti experience in Argentina, returns with a short story collection that runs the genre gamut from gritty realism and social satire to science fiction and fantasy. The throughline is Villada's boundless imagination, whether she's conjuring the chaos of the Mexican Inquisition or a trans sex worker befriending a down-and-out Billie Holiday. Angie Cruz calls this "one of my favorite short-story collections of all time." —SMS

The Editor by Sara B. Franklin [NF]

Franklin's tenderly written and meticulously researched biography of Judith Jones—the legendary Knopf editor who worked with such authors as John Updike, Sylvia Plath, Elizabeth Bowen, Anne Tyler, and, perhaps most consequentially, Julia Child—was largely inspired by Franklin's own friendship with Jones in the final years of her life, and draws on a rich trove of interviews and archives. The Editor retrieves Jones from the margins of publishing history and affirms her essential role in shaping the postwar cultural landscape, from fiction to cooking and beyond. —SMS

The Book-Makers by Adam Smyth [NF]

A history of the book told through 18 microbiographies of particularly noteworthy historical personages who made them? If that's not enough to convince you, consider this: the small press is represented here by Nancy Cunard, the punchy and enormously influential founder of Hours Press who romanced both Aldous Huxley and Ezra Pound, knew Hemingway and Joyce and Langston Hughes and William Carlos Williams, and has her own MI5 file. Also, the subject of the binding chapter is named "William Wildgoose." —JHM

June

June 4

The Future Was Color by Patrick Nathan [F]

A gay Hungarian immigrant writing crappy monster movies in the McCarthy-era Hollywood studio system gets swept up by a famous actress and brought to her estate in Malibu to write what he really cares about—and realizes he can never escape his traumatic past. Sunset Boulevard is shaking. —JHM

A Cage Went in Search of a Bird [F]

This collection brings together a who's who of literary writers—10 of them, to be precise— to write Kafka fanfiction, from Joshua Cohen to Yiyun Li. Then it throws in weirdo screenwriting dynamo Charlie Kaufman, for good measure. A boon for Kafkaheads everywhere. —JHM

We Refuse by Kellie Carter Jackson [NF]

Jackson, a historian and professor at Wellesley College, explores the past and present of Black resistance to white supremacy, from work stoppages to armed revolt. Paying special attention to acts of resistance by Black women, Jackson attempts to correct the historical record while plotting a path forward. Jelani Cobb describes this "insurgent history" as "unsparing, erudite, and incisive." —SMS

Holding It Together by Jessica Calarco [NF]

Sociologist Calarco's latest considers how, in lieu of social safety nets, the U.S. has long relied on women's labor, particularly as caregivers, to hold society together. Calarco argues that while other affluent nations cover the costs of care work and direct significant resources toward welfare programs, American women continue to bear the brunt of the unpaid domestic labor that keeps the nation afloat. Anne Helen Petersen calls this "a punch in the gut and a call to action." —SMS

Miss May Does Not Exist by Carrie Courogen [NF]

A biography of Elaine May—what more is there to say? I cannot wait to read this chronicle of May's life, work, and genius by one of my favorite writers and tweeters. Claire Dederer calls this "the biography Elaine May deserves"—which is to say, as brilliant as she was. —SMS

Fire Exit by Morgan Talty [F]

Talty, whose gritty story collection Night of the Living Rez was garlanded with awards, weighs the concept of blood quantum—a measure that federally recognized tribes often use to determine Indigenous membership—in his debut novel. Although Talty is a citizen of the Penobscot Indian Nation, his narrator is on the outside looking in, a working-class white man named Charles who grew up on Maine’s Penobscot Reservation with a Native stepfather and friends. Now Charles, across the river from the reservation and separated from his biological daughter, who lives there, ponders his exclusion in a novel that stokes controversy around the terms of belonging. —NodB

June 11

The Material by Camille Bordas [F]

My high school English teacher, a somewhat dowdy but slyly comical religious brother, had a saying about teaching high school students: "They don't remember the material, but they remember the shtick." Leave it to a well-named novel about stand-up comedy (by the French author of How to Behave in a Crowd) to make you remember both. --SMS

Ask Me Again by Clare Sestanovich [F]

Sestanovich follows up her debut story collection, Objects of Desire, with a novel exploring a complicated friendship over the years. While Eva and Jamie are seemingly opposites—she's a reserved South Brooklynite, while he's a brash Upper Manhattanite—they bond over their innate curiosity. Their paths ultimately diverge when Eva settles into a conventional career as Jamie channels his rebelliousness into politics. Ask Me Again speaks to anyone who has ever wondered whether going against the grain is in itself a matter of privilege. Jenny Offill calls this "a beautifully observed and deeply philosophical novel, which surprises and delights at every turn." —LA

Disordered Attention by Claire Bishop [NF]

Across four essays, art historian and critic Bishop diagnoses how digital technology and the attention economy have changed the way we look at art and performance today, identifying trends across the last three decades. A perfect read for fans of Anna Kornbluh's Immediacy, or the Style of Too Late Capitalism (also from Verso).

War by Louis-Ferdinand Céline, tr. Charlotte Mandell [F]

For years, literary scholars mourned the lost manuscripts of Céline, the acclaimed and reviled French author whose work was stolen from his Paris apartment after he fled to Germany in 1944, fearing punishment for his collaboration with the Nazis. But, with the recent discovery of those fabled manuscripts, War is now seeing the light of day thanks to New Directions (for anglophone readers, at least—the French have enjoyed this one since 2022 courtesy of Gallimard). Adam Gopnik writes of War, "A more intense realization of the horrors of the Great War has never been written." —DF

The Uptown Local by Cory Leadbeater [NF]

In his debut memoir, Leadbeater revisits the decade he spent working as Joan Didion's personal assistant. While he enjoyed the benefits of working with Didion—her friendship and mentorship, the more glamorous appointments on her social calendar—he was also struggling with depression, addiction, and profound loss. Leadbeater chronicles it all in what Chloé Cooper Jones calls "a beautiful catalog of twin yearnings: to be seen and to disappear; to belong everywhere and nowhere; to go forth and to return home, and—above all else—to love and to be loved." —SMS

Out of the Sierra by Victoria Blanco [NF]

Blanco weaves storytelling with old-fashioned investigative journalism to spotlight the endurance of Mexico's Rarámuri people, one of the largest Indigenous tribes in North America, in the face of environmental disasters, poverty, and the attempts to erase their language and culture. This is an important book for our times, dealing with pressing issues such as colonialism, migration, climate change, and the broken justice system. —CK

Any Person Is the Only Self by Elisa Gabbert [NF]

Gabbert is one of my favorite living writers, whether she's deconstructing a poem or tweeting about Seinfeld. Her essays are what I love most, and her newest collection—following 2020's The Unreality of Memory—sees Gabbert in rare form: witty and insightful, clear-eyed and candid. I adored these essays, and I hope (the inevitable success of) this book might augur something an essay-collection renaissance. (Seriously! Publishers! Where are the essay collections!) —SMS

Tehrangeles by Porochista Khakpour [F]

Khakpour's wit has always been keen, and it's hard to imagine a writer better positioned to take the concept of Shahs of Sunset and make it literary. "Like Little Women on an ayahuasca trip," says Kevin Kwan, "Tehrangeles is delightfully twisted and heartfelt." —JHM

Traveling: On the Path of Joni Mitchell by Ann Powers [NF]

The moment I saw this book's title—which comes from the opening (and, as it happens, my favorite) track on Mitchell's 1971 masterpiece Blue—I knew it would be one of my favorite reads of the year. Powers, one of the very best music critics we've got, masterfully guides readers through Mitchell's life and work at a fascinating slant, her approach both sweeping and intimate as she occupies the dual roles of biographer and fan. —SMS

All Desire Is a Desire for Being by René Girard, ed. Cynthia L. Haven [NF]

I'll be honest—the title alone stirs something primal in me. In honor of Girard's centennial, Penguin Classics is releasing a smartly curated collection of his most poignant—and timely—essays, touching on everything from violence to religion to the nature of desire. Comprising essays selected by the scholar and literary critic Cynthia L. Haven, who is also the author of the first-ever biographical study of Girard, Evolution of Desire, this book is "essential reading for Girard devotees and a perfect entrée for newcomers," per Maria Stepanova. —DF

June 18

Craft by Ananda Lima [F]

Can you imagine a situation in which interconnected stories about a writer who sleeps with the devil at a Halloween party and can't shake him over the following decades wouldn't compel? Also, in one of the stories, New York City’s Penn Station is an analogue for hell, which is both funny and accurate. —JHM

Parade by Rachel Cusk [F]

Rachel Cusk has a new novel, her first in three years—the anticipation is self-explanatory. —SMS

Little Rot by Akwaeke Emezi [F]

Multimedia polymath and gender-norm disrupter Emezi, who just dropped an Afropop EP under the name Akwaeke, examines taboo and trauma in their creative work. This literary thriller opens with an upscale sex party and escalating violence, and although pre-pub descriptions leave much to the imagination (promising “the elite underbelly of a Nigerian city” and “a tangled web of sex and lies and corruption”), Emezi can be counted upon for an ambience of dread and a feverish momentum. —NodB

When the Clock Broke by John Ganz [NF]

I was having a conversation with multiple brilliant, thoughtful friends the other day, and none of them remembered the year during which the Battle of Waterloo took place. Which is to say that, as a rule, we should all learn our history better. So it behooves us now to listen to John Ganz when he tells us that all the wackadoodle fascist right-wing nonsense we can't seem to shake from our political system has been kicking around since at least the early 1990s. —JHM

Night Flyer by Tiya Miles [NF]

Miles is one of our greatest living historians and a beautiful writer to boot, as evidenced by her National Book Award–winning book All That She Carried. Her latest is a reckoning with the life and legend of Harriet Tubman, which Miles herself describes as an "impressionistic biography." As in all her work, Miles fleshes out the complexity, humanity, and social and emotional world of her subject. Tubman biographer Catherine Clinton says Miles "continues to captivate readers with her luminous prose, her riveting attention to detail, and her continuing genius to bring the past to life." —SMS

God Bless You, Otis Spunkmeyer by Joseph Earl Thomas [F]

Thomas's debut novel comes just two years after a powerful memoir of growing up Black, gay, nerdy, and in poverty in 1990s Philadelphia. Here, he returns to themes and settings that in that book, Sink, proved devastating, and throws post-service military trauma into the mix. —JHM

June 25

The Garden Against Time by Olivia Laing [NF]

I've been a fan of Laing's since The Lonely City, a formative read for a much-younger me (and I'd suspect for many Millions readers), so I'm looking forward to her latest, an inquiry into paradise refracted through the experience of restoring an 18th-century garden at her home the English countryside. As always, her life becomes a springboard for exploring big, thorny ideas (no pun intended)—in this case, the possibilities of gardens and what it means to make paradise on earth. —SMS

Cue the Sun! by Emily Nussbaum [NF]

Emily Nussbaum is pretty much the reason I started writing. Her 2019 collection of television criticism, I Like to Watch, was something of a Bible for college-aged me (and, in fact, was the first book I ever reviewed), and I've been anxiously awaiting her next book ever since. It's finally arrived, in the form of an utterly devourable cultural history of reality TV. Samantha Irby says, "Only Emily Nussbaum could get me to read, and love, a book about reality TV rather than just watching it," and David Grann remarks, "It’s rare for a book to feel alive, but this one does." —SMS

Woman of Interest by Tracy O'Neill [NF]

O’Neill's first work of nonfiction—an intimate memoir written with the narrative propulsion of a detective novel—finds her on the hunt for her biological mother, who she worries might be dying somewhere in South Korea. As she uncovers the truth about her enigmatic mother with the help of a private investigator, her journey increasingly becomes one of self-discovery. Chloé Cooper Jones writes that Woman of Interest “solidifies her status as one of our greatest living prose stylists.” —LA

Dancing on My Own by Simon Wu [NF]

New Yorkers reading this list may have witnessed Wu's artful curation at the Brooklyn Museum, or the Whitney, or the Museum of Modern Art. It makes one wonder how much he curated the order of these excellent, wide-ranging essays, which meld art criticism, personal narrative, and travel writing—and count Cathy Park Hong and Claudia Rankine as fans. —JHM

[millions_email]

What the Caged Bird Feels: A List of Writers in Support of Vegetarianism

Growing up as a vegetarian in rural England in the ’90s, I was sometimes under the impression that my lifestyle was unusual—if not radical. In recent years, vegetarianism (and reduced-meat diets) have become more mainstream even in rural areas.

With time I’ve come to realize that there have always been vegetarians and vegetarian communities. Perhaps the more interesting ones for me are the artists and thinkers who go against the grain, choosing to think and live differently from the people around them. There is sometimes difficulty in ascertaining the validity of claims that certain historical figures actually followed a vegetarian lifestyle. For Da Vinci we have both Giorgio Vasari’s accounts and the letters between Andrea Corsali and Da Vinci’s patron Giuliano de’ Medici as convincing sources; for Pythagoras we have a number of ancient sources, as well as his enduring legacy. My awareness of Albert Einstein’s vegetarianism comes from primary sources—letters to Hans Muehsam and Max Kariel.

I will employ the term “vegetarian sentiment” here, as vegetarianism and veganism are ideologies before they are followed through in lifestyle and dietary choices. There are many writers and thinkers who advocate for vegetarianism and/or animal rights but still consume flesh meat. There’s Alice Walker, who I’ll talk about in more detail later; there’s Voltaire, who argued fervently against Descartes’s belief that animals were mere machines (though he may have been a practicing vegetarian based on what he writes in Dictionnaire Philosophique: “Men fed upon carnage, and drinking strong drinks, have all an impoisoned and acrid blood which drives them mad in a hundred different ways.”

Anna Sewell, through her children’s novel Black Beauty, taught young and old readers about how to treat both animals and humans with kindness—and in turn spurred progression in the animal welfare movement.

Raskolinov’s fearful horse dream in Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment is symbolic of what is soon to come—though also revelatory of what the author feels about animals. In his later novel The Brothers Karamazov, there’s a discussion between Alyosha and the elder Zosima:

Love animals: God has given them the rudiments of thought and joy untroubled. Do not trouble their joy, don't harass them, don't deprive them of their happiness, don't work against God's intent. Man, do not pride yourself on superiority to animals; they are without sin, and you, with your greatness, defile the earth by your appearance on it, and leave the traces of your foulness after you—alas, it is true of almost every one of us!

Suffragists who fought for women’s rights were also heavily involved in campaigning against vivisection and the consumption of meat. Many suffragists thought that the adoption of a vegetarian diet could herald a new world where women were not confined to the kitchens. Carol J. Adams writes in her book The Sexual Politics of Meat (extract obtained from Stuff Mom Never Told You):

We can follow the historic alliance of feminism and vegetarianism in Utopian writings and societies, antivivisection activism, the temperance and suffrage movements, and twentieth century pacifism. Hydropathic institutes in the nineteenth century, which featured vegetarian regimens, were frequented by Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Sojourner Truth, and others. At a vegetarian banquet in 1853, the gathered guests lifted their alcohol-free glasses to toast: “Total Abstinence, Women's Rights, and Vegetarianism.”

Recently a friend came to me asking for a recommendation for vegetarian literature. I was taken a little off guard, for I have never actively searched for books on vegetarianism. Why read to be convinced of an opinion I already share? Though I realized that I had read books by vegetarian authors (of fiction), and writers who have expressed a vegetarian sentiment. And though I couldn’t answer his question, it compelled me to pick up work by authors whose experiences of (and sometimes motivations for) vegetarianism were entirely different from my own.

While far from exhaustive, I shall discuss some among them here.

1. Franz Kafka

Max Brod is often remembered as the friend who wouldn’t burn Franz Kafka’s life’s work, as was asked of him by Kafka, instead publishing it posthumously. If it were not for his refusal to follow his friend’s instructions, we might not have stories such as The Metamorphosis and The Castle. But Brod was also a prolific published writer during his lifetime, and he eventually became Kafka’s biographer. Much of what we know about Kafka comes from Brod, including his experimentation with different diets—in part to ease his lifelong sickness.

One of the most striking images from Franz Kafka: A Biography is where Brod recalls how Kafka, a recently turned strict vegetarian, once visited the Berlin aquarium:

Suddenly he began to speak to the fish in their illuminated tanks, “Now at last I can look at you in peace, I don't eat you any more.” ...

Among my notes I find something else that Kafka said about vegetarianism...He compared vegetarians with the early Christians, persecuted everywhere, everywhere laughed at, and frequenting dirty haunts. “What is meant by its nature for the highest and the best, spreads among the lowly people.”

In a letter from Brod to Kafka’s fiancee Felice Bauer, Brod writes:

After years of trial and error Franz has at last found the only diet that suits him, the vegetarian one. For years he suffered from his stomach; now he is as healthy and as fit as I have ever known him. Then along come his parents, of course, and in the name of love try to force him back into eating meat and being ill—it is just the same with his sleeping habits. At last he has found what suits him best, he can sleep, can do his duty in that senseless office, and get on with his literary work. But then his parents...This really makes me bitter.

2. Jonathan Safran Foer

Jonathan Safran Foer returns to fellow Jewish writer Kafka’s moment at the Berlin aquarium throughout his first nonfiction work, Eating Animals. The book is the result of three years spent immersed in the world of animal agriculture. This was in part motivated by a desire to make an informed decision about what to feed his newborn son—but also to become more resolved with regard to his wavering vegetarianism. He makes the invisible realities for factory-farmed animals visible for himself and the reader, forcing us to think about what is impaled on our forks.

Eating Animals is essentially his own denunciation of factory farming, but it is also a reflection on the culture that surrounds meat eating: the history of ambivalence toward carnism; societal hypocrisies; the myth of consent and other stories cultures create for themselves to justify slaughter; the language we use to devalue some animals but place value in others that we love as companions.

In several places, Safran Foer refers back to that moment when Kafka looks at fish at the Berlin aquarium. He uses Walter Benjamin’s interpretation of Kafka’s animal tales to frame this part of his own story. Benjamin tells us how Kafka’s animals are “receptacles of forgetting,” while shame—as paraphrased by Safran Foer—is “a response and a responsibility before invisible others.”

“What had moved Kafka to become vegetarian?” asks Safran Foer:

A possible answer lies in the connection Benjamin makes, on the one hand, between animals and shame, and on the other, between animals and forgetting. Shame is the work of memory against forgetting. Shame is what we feel when we almost entirely—yet not entirely—forget social expectations and our obligations to others in favor of our immediate satisfaction.

Shame doesn’t just prompt forgetting about the animals we harm. “What we forget about animals,” writes Safran Foer, “we begin to forget about ourselves.”

During the spring of 2007, Safran Foer lived in Berlin with his family, and they would visit the aquarium Kafka had visited the previous century—and like him, they would stare into the tanks at the sea life. “As a writer aware of that Kafka story, I came to feel a certain kind of shame at the aquarium,” he writes. Among the various manifestations of shame he experienced: shame at feeling “grossly inadequate” compared to his hero, shame at being a Jew in Berlin:

And then there was the shame in being human: the shame of knowing that twenty of the roughly thirty-five classified species of seahorse worldwide are threatened with extinction because they are killed “unintentionally” in seafood production. The shame of indiscriminate killing for no nutritional necessity or political cause or irrational hatred or intractable human conflict.

For Safran Foer, remembering thwarts forgetting when he visits the kill floor of Paradise Locker Meats and looks into the eyes of a pig who is minutes away from being slaughtered; he didn’t quite feel at ease being the pig’s last sight, though what he felt wasn’t quite shame either. “The pig wasn’t a receptacle of my forgetting,” he writes. “The animal was a receptacle of my concern. I felt—I feel—relief in that. My relief doesn’t matter to the pig. But it matters to me.”

3. Alice Walker

“KNOW what the caged bird feels,” wrote Paul Laurence Dunbar in a poem entitled “Sympathy.” With this poem, Dunbar—who was born to parents who had been enslaved before the American Civil War—opened up this dreaded comparison between human and animal slavery. The line was borrowed by Maya Angelou for the title of her autobiography, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings.

Most will feel uncomfortable with comparisons between animal suffering and human suffering—the title of Marjorie Spiegel’s The Dreaded Comparison acknowledges this. The African-American writer and self-described womanist Alice Walker, known best perhaps for The Color Purple, prefaced Marjorie Spiegel’s controversial title. Walker writes, “It is a comparison that, even for those of us who recognize its validity, is a difficult one to face. Especially so, if we are the descendants of slaves. Or of slave owners. Or of both. Especially so if we are also responsible in some way for the present treatment of animals.”

Though Walker acknowledges the difficulty of this comparison, she concludes that she agrees with Spiegel’s line of reason: “The animals of the world exist for their own reasons. They were not made for humans any more than black people were made for whites or women for men. This is the gist of Spiegel’s cogent, humane and astute argument, and it is sound.”

Walker is not a vegetarian. In a book entitled The Chicken Chronicles, the author writes about her relationship with her flock of chickens. Rather than turn her head, Walker confronts her food vis-à-vis—in this way, the chicken is not a receptacle of her forgetting. Interviewer Diane Rehm expressed surprise upon learning that Walker eats birds. “I know, I know. It's a contradiction and I have been a vegan and I've been a vegetarian,” replied Walker, “but from time to time, I do eat chicken. I grew up on chicken and I accept that.”

Vegetarianism, or veganism, is something to which Walker seems to aspire, though. To an audience at Emory University, the author talks about her love of cows and says she is glad she doesn’t eat them. She then recites a short poem she wrote for an Italian friend who wanted help giving up meat, “La Vaca”:

Look

into

her eyes

and know:

She does not think

of

herself

as

steak.

[millions_ad]

4. Isaac Bashevis Singer

The comparison between human and animal slavery is not the only dreaded comparison; the Nobel laureate Isaac Bashevis Singer has become the classic reference for comparisons between intensive farming and the Holocaust. In “The Letter Writer,” he wrote, "In relation to [animals], all people are Nazis; for the animals, it is an eternal Treblinka."

Singer was born in a village near Warsaw, Poland. His father was a Hasidic rabbi, while his mother was the daughter of the rabbi of Bilgoraj. Singer seemed destined to become a rabbi, too, though a brief enrollment at a rabbinical school turned him off the idea. He worked brief stints in a number of fields before emigrating to the United States, fearful of the rise of Nazism in neighboring Germany. In New York City he worked as a journalist for a Yiddish-language newspaper before penning his own novels and short stories, including The Slave and The Family Moskat.

Vegetarianism crops up often in his work. Yet it is nowhere near as explicit as in “The Slaughterer,” a short story which first appeared in The New Yorker in 1967 and now resides in The Collected Stories of Isaac Bashevis Singer. The story follows Yoineh Meir, a Jew who—like Singer—seems destined to become a rabbi. A competitor takes Meir’s place, and instead he is offered the role of the town’s ritual slaughterer. The career causes him daily anguish and eventually leads to his own untimely demise. The story is graphic and bloody, the protagonist sensitive and empathetic toward all living creatures:

Yoneih Meir no longer slept at night. If he dozed off, he was immediately beset by nightmares. Cows assumed human shape, with beards, and skullcaps over their horns. Yoineh Meir would be slaughtering a calf, but it would turn into a girl. Her neck throbbed, and she pleaded to be saved. She ran to the study house and splattered the courtyard with her blood. He even dreamed that he had slaughtered [his wife] instead of a sheep.

Yoineh Meir extends his love toward all animals when he realizes what it means to kill one. Later in the narrative, Singer writes that “when you slaughter a creature, you slaughter God.”

5. J.M. Coetzee

In his metafictional novella The Lives of Animals, Coetzee’s alter ego and fictional novelist Elizabeth Costello is invited to be a guest lecturer at a university’s annual literary seminary. Rather than talk about literature, she decides to talk about animal cruelty and in several places compares the mass slaughter of animals to the Holocaust:

The people who lived in the countryside around Treblinka—Poles, for the most part—said that they did not know what was going on in the camp; said that, while in a general way they might have guessed what was going on, they did not know for sure; said that, while in a sense they might have known, in another sense they did not know, could not afford to know, for their own sake. ...

I return one last time to the places of death all around us, the places of slaughter to which, in a huge communal effort, we close our hearts. Each day a fresh holocaust, yet, as far as I can see, our moral being is untouched. ...

It was from the Chicago stockyards that the Nazis learned how to process bodies.

We know Coetzee is a vegetarian and active animal rights advocate, though in The Lives of Animals it becomes difficult to distinguish between Elizabeth Costello’s views and J. M. Coetzee’s. He has written several op-eds for the Sydney Herald about beliefs we can safely say are his own.

In one article, Coetzee criticizes the manner in which consumers tend to idealize family farms:

It would be a mistake to idealize traditional animal husbandry as the standard by which the animal products industry falls short. Traditional animal husbandry is brutal enough, just on a smaller scale. A better standard by which to judge both practices would be the simple standard of humanity: is this truly the best that humans are capable of?

In another, Coetzee expresses his optimism concerning the compassion of children: “It takes but one glance into a slaughterhouse to turn a child into a lifelong vegetarian.”

6. V.S. Naipaul

V.S. Naipaul has a visceral response to the sight and smell of meat. Naipaul was born in Trinidad; unusual among Indian laborers in the Caribbean region, Naipaul’s paternal grandfather was a Brahmin—the highest ranked caste among Hindus in India. Naipaul’s father also claimed this distinction, though the validity of his claim is less clear. Often, due to general caste rules, Brahmins distinguish themselves from other castes by adhering to a strict vegetarian diet. All Hindus aspire to transcend this life through self-realization—halting the transmigration from one body to the next. To do so, in their daily lives they must act in accordance with the tenets of Sattva Guna (mode of goodness) laid out in the Bhagavad Gita, a Hindu scripture which includes the abstention of flesh meat.

For many Hindus who follow a lacto-vegetarian diet, the ideological reasons for not eating animals are still ever present—for others, it is merely a distinction inherited from the cultural context into which they were born. I don’t know which category Naipaul fits into. He has, to the best of my knowledge, never spoken openly about any ideological reason for his vegetarianism.

He has, however, written about his disgust at the sight of meat. What is perhaps the first mention is in his early work Between Father and Son: Family Letters. A young Naipaul received a scholarship to study at Oxford, where he found himself struggling with depression and loneliness. In a bid to bridge the distance between continents, he wrote letters to his family—a correspondence that lasted four years and ended with the death of his father. In a letter to his elder sister Kamla, dated Sept. 21, 1949, he recapitulates a distressing situation during an Old Boy’s Association dinner: “Special arrangements, I was informed after dinner, had been made for me but these appeared to have been limited to serving me potatoes in different ways—now fried, now boiled.” Turtle soup was served to the other diners; being vegetarian, Naipaul asked the manager for corn soup instead. “He ignored this and the waiter bought me a plateful of green slime. This was the turtle soup. I was nauseated and annoyed and told the man to take it away. This, I was told, was a gross breach of etiquette.”

7. Leo Tolstoy

Vegetarianism was the focal point of several of his essays and tied in with his pre-existing beliefs in the benefits of abstinence. In On Civil Disobedience, for example, Tolstoy writes, “A man can live and be healthy without killing animals for food; therefore, if he eats meat, he participates in taking animal life merely for the sake of his appetite. And to act so is immoral.”

Tolstoy originally wrote The First Step as the foreword to The Ethics of Diet by Howard Williams. In it, Tolstoy encourages readers to practice harmlessness: “If a man aspires towards a righteous life, his first act of abstinence is from injury to animals.” He also suggests that vegetarianism is humanity’s natural state: “So strong is humanity's aversion to all killing. But by example, by encouraging greediness, by the assertion that God has allowed it, and above all by habit, people entirely lose this natural feeling.”

He wrote extensively about violence, and in a letter to Mahatma Gandhi published later as A Letter to a Hindu, Tolstoy convinced Gandhi to use nonviolent resistance to gain independence from the British colonial rule in the Indian peninsula. In his essay “What I Believe,” Tolstoy emphasizes his conviction that we become more violent by inflicting suffering upon animals: “As long as there are slaughter houses there will always be battlefields.”

Four years after Tolstoy’s death, his private secretary Valentin Bulgakov wrote an article for London-based The Vegetarian News to celebrate Tolstoy’s “great service to the vegetarian movement” during the last 23 years of his life. The article ends like this:

I close what I have to say with the words of Leo Tolstoy himself: “Here, indeed, outwardly, are we met but inwardly we are bound to every living creature. Already are we conscious of many of the motions of the spiritual world, but others have not yet been borne in upon us. Nevertheless they come, even as the earth presently comes to see the light of the stars, which to our eyes at this moment is invisible.”

Image: Flickr/ilovebutter

Books Are Garbage

Books are sacred objects. Books are garbage. Between, the books with badly bent covers on the parsons tables of Midas Muffler and orthopedists’ waiting rooms. Books bought by the yard to complement the colors in the redecorated den. The tumbled remainders of remainders on the dollar store shelf, Geoff Dyer next to Christian fiction. The gorgeously designed new releases presented on the tabletops of independent bookstores as if they were hand-painted confections in a vitrine at Teuscher. Then there is the final stop, where some books are no longer figurative garbage. They are actual trash.

I no longer go to church, since here in the Catskills we have the dump. Ours is the purest iteration of the cathedral: on a windswept rise under a ceiling of sky, the enclosing mountains the choir waiting silently to begin. Beneath the metal eaves of a soaring peaked roof, mortal leavings gather.

The dump’s offering plate is a discarded sideboard on which parishioners jettison belongings someone else might yet find useful. Old plates. Used mugs. Videotapes (Sylvester Stallone in his salad days, Jane Fonda in very small workout wear, cartoon features once prized by children). Stuffed animals. Inscrutable decorations for such holidays as the Festooning of the Kitchen with Inspirational Adages on Little Faux Chalkboards. Books. Boxes and boxes of books, soaking up the ambient humidity and anything that might have spilled on its way to interment in the great roll-off sepulchers that swallow couches, wheels that will never roll again, and black plastic bags in their hundreds. Books that are no longer wanted, because—Long-ago read? Owners moved, downsizing, died? Gifts from now-despised givers?

Here is where a book reaches the bottom of the narrative ladder that, as in Black Beauty, describes life’s trajectory ever downward, unless, at the end sudden redemption plucks the unfortunate from final doom. I root through piles of superannuated World Book Encyclopedias and Ultimate Grill cookbooks and find what I am looking for but did not know I was. More than occasionally slightly mildewed, but that’s not always a disqualifier.

These are the definition of a gift. They stir the rescuer’s impulse; they recall past happy lives spent in narrow aisles of the Strand, sitting on the floor at the old used-textbook annex of the Barnes & Noble on Fifth Avenue, book barns and yard sales and stoop sales. Not that I’ve never offloaded books myself. A library fair finally received the collection of philosophy and Middle English works I realized, after boxing and unboxing them through the course of several moves, would never be cracked again. I don’t like to get rid of books, though I do—they tell a personal history, I imagine with obvious false hope, my grandchildren will one day be fascinated to trace. Never at the dump, though. I use the dump for retrieval only.

[millions_email]

Today the gems do not hide. They are in their open box. Today’s trash is the complete Emily Dickinson in hardcover, with dust jacket. Today’s detritus is an unread Penguin Classics Don Quixote. Today’s undesirable is Of Human Bondage in a Modern Library edition. The sight of a virgin Penguin is alluring enough. But it’s the running torchbearer on the cover of a Modern Library that rouses an atavistic urge sharp as hunger. The Modern Library editions my parents collected when they were in college were the backdrop against which the cinema of life unreeled. Of course I would collect them myself as soon as I was on my own. I was the reader envisioned by Boni & Liveright in 1917 when they conceived the Modern Library imprint: eager to attain culture in the form of immortal literature, but short-pocketed.

I begin reading that night. Philip, the misplaced orphan, who is like a book and also like Maugham himself, finds lost volumes on a shelf. Philip’s severe guardian bought books reflexively but did not read much: “he forgot the odd lots he had bought at one time and another because they were cheap.” And so, among the dry dust of pedagogy, Philip finds some real “old-fashioned novels.” As he read, he forgot “the life about him” and “formed the most delightful habit in the world, the habit of reading: he did not know that thus he was providing himself with a refuge from all the distress of life; he did not know either that he was creating for himself an unreal world which would make the real world of every day a source of bitter disappointment.” How had I missed Maugham before?

What you had forgotten, the dump remembers. It addresses all manner of grave omissions and gaps. That is what I want to believe, and at my place of worship I believe anything I wish.

Whatever led these books to have been discarded sometime close to my Friday 11 a.m. visit? I don’t know. Happenstance is a meaningless miracle with no origin. The dump and what you find there, or don’t, is just one of those things.

I open the cover and see this was a book meant for the long haul, for possession and the permanent shelf. The original owner had affixed a bookplate. These delightful claims on the posterity of one’s books have fallen into disuse. Because the idea of building a library—a lasting monument to character—has itself fallen into disuse in days when it is a moral superiority to get rid of the “unuseful.” The plate is an atmospheric woodcut depicting two figures (or perhaps the same one in a time-lapse portrayal of hope), one defeated and one who has risen to gesture aspiringly at the night sky. Ad Astra reads its legend—To the Stars.

In another two weeks my own garbage has piled up warningly, predictable as few things are anymore. The lids on the recycling bins are askew, plastic and tin looking to make their escape. So I load the truck again. I don’t permit myself to look at the old sideboard until I’ve finished my final task: a walk down the hill to the scrap metal mountain, there to toss with a clang the Christmas tree holder that’s outlived its usefulness. Then I head back up and into the nave, eye searching for the telltale heap of cardboard boxes that signals ripe pickings. No such luck. There is only one small box on the ground; I fear an old Thermos or, worse, pot holders. Instead—and this I swear, for only a sociopath lies in church—there are only two books. I am suddenly struck, or struck back to the moment where you get born again.

As if one begat the other, the two are stacked, bound together by the design of serendipity. What I see is a message. What I see is The Anatomy of Revolution arising from The Nature of Prejudice.

I have been an atheist for decades, but I have also long bent to collect pennies from the dirt, believing them portents of luck. The dump embraces both aspects of an inexplicable persistence. It is a place of generosity. It is an oracle. Today I think I was right about the church part. Maybe only god can help us now. But first, I look well at what is found by chance at the same time it is put right in my hands.

Image Credit: Pexels/Wendelin Jacober.

Born from Books: Six Authors on Their Childhood Reading

Books are our first, and sometimes best, teachers. I inherited the books of my older brothers. While they were away at college, I went into their rooms and stacked and arranged the titles by color and letter. My two favorite relics from their childhood were Punt, Pass and Kick and The How and Why Wonder Book of Stars. The diagrams of movement across the gridiron reminded me of the constellation maps. I appreciated that athletic bodies and celestial bodies were in constant motion, and yet might be captured in a single glance.

I was years away from the writing instruction of workshops and line edits, or the training of literary analysis. Those early years of reading were charged with the stuff of raw imagination. After I exhausted the books of my brothers, my parents took me to the library and used book sales. I wanted to run and play basketball, but I also wanted to read until I fell asleep, chin planted on open pages. My father had been a college football player who studied theology; my mother read history and poetry and told stories with layers and layers of detail. I was raised to appreciate words and to embrace wonder.

It might be because I teach young students, but I am endlessly fascinated by the routes of our reading lives. I seek interviews with writers because I look for their origin stories. I want to pinpoint the moment reading became a life-breathing activity. I am particularly drawn to the memories of writers whose imaginations remains raw and jarring; writers who are “charged,” to borrow the language of Gerard Manley Hopkins.

I contacted six writers with such imaginations, and am happy to share their memories about the books that were most formative during their childhoods.

1. Nina McConigley, author of Cowboys and East Indians:

It's hard to grow up in the American West and not read Laura Ingalls Wilder. I read all the Little House on the Prairie books at a young age, and I was in love with the whole pioneer narrative. Like Laura, my parents had traveled far to make a home in the West. I also came to love the simplicity of her language and her storytelling. She had no sentimentality. She would so matter-of-factly say the worst news: Mary was blind. The crops failed. It was a sad day though when I realized Laura and I would not have been friends. Her ma hated Indians (albeit the other kind), and the books weren't that kind to others or brown people. But I marveled over her making a lot out of little -- sewing, canning, simple pleasures. But I mostly connected with how Laura loved the land—the prairies and woods, the sky and open-- which were so important to me as a little girl in Wyoming.

Since my parents both grew up in colonized countries -- India and Ireland, much of what they read as children was British. So, as a little girl, I was introduced to Enid Blyton, who seemed to be the most prolific writer ever. She wrote several series from the Famous Five and Secret Seven to scores of boarding school narratives like The O'Sullivan Twins or The Naughtiest Girl. But what I loved were her fairy stories. She wrote a trilogy about a magic tree which started with The Enchanted Wood. In the book, three children found a magic tree, and climbed it -- and at the top was a series of ever-changing lands -- The Land of Birthdays, The Land of Sweets. I think as a brown kid living in Wyoming, these books were the ultimate in escapism. I was transported into a forest in England where the world was constantly shifting. I found this extremely comforting. I would often find myself climbing the big cottonwood tree in our backyard, hoping I would be taken away by something bigger than me.

2. William Giraldi, author of Hold the Dark:

In the late 1980s, Time-Life Books had a popular, 33-volume series called Mysteries of the Unknown. At 11 years old, I didn’t know enough to be irked by the redundant title -- all mysteries are unknown: that’s the definition of “mystery” -- and so I grabbed the phone (Time-Life advertised on television) and soon began receiving books on UFOs and the Loch Ness Monster, poltergeists and Sasquatch, Atlantis and the Bermuda Triangle and the Great Pyramid of Giza, werewolves and vampires and witches. For a cradle Roman Catholic reared in only one acceptable species of the supernatural, these titles seemed great feats of transgression and betrayal, fonts of the extraordinary and occult, a concussion of the spiritual and the cerebral, the factual and the fantastical. The books were mostly cascades of conjecture and fatuity, of course, but they rubbed against my imagination in all the ways I needed then. Mystery is another word for hope; monsters are how we make sense of ourselves. New Jersey seemed so drab without them. In the years after the Time-Life series, I’d be found by Poe and Stoker, by Stevenson and Wells, and then it was off into the more “serious” stuff: important books, yes, but hardly ever as wondrous.

3. Sara Eliza Johnson, author of Bone Map:

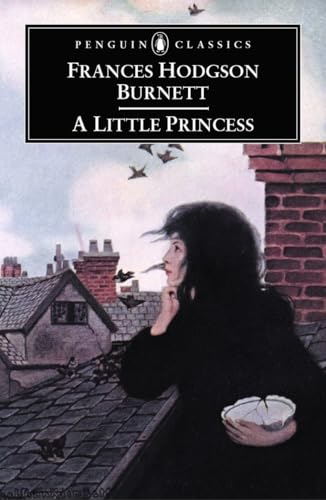

I remember loving Black Beauty and A Little Princess, which was my mother’s favorite book as a girl (and one reason for my name, which has no “h!”). I also read a lot of series meant for young girls -- Nancy Drew, The Babysitters Club, the Ramona Quimby books -- though my absolute favorite series was Goosebumps. R.L. Stine wrote the original series in my prime formative reading years, from 1992 (when I was eight years old) to 1997 (when I was 13), and I was always so excited when a new one came out. My early love of Goosebumps (as well as the Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark series) blossomed into the unapologetic affection for the horror genre I have today, a lonely affection to have in adulthood! But my favorite book as a child was probably The Giver, which, like many in my generation, I read for English class at the beginning of sixth grade. It was my first taste of dystopia, and so, in some ways, the first challenge to my world, and the first literary protagonist with whom I truly felt a kinship. When Jonas receives from the Giver the unwieldy collection of memories his monotone community has buried -- of pain, war, starvation, but also pleasure and art -- he becomes isolated and lonely in a way I think that I sometimes felt then, as a shy child without siblings. In the Receiving process, memory is a physical phenomenon literally subsumed and experienced by the body, as when Jonas receives the memory of a broken leg and feels as if his leg is broken -- an early reminder that these entities we often consider purely psychological, such as memory, language, and dream, have physical and even physiological presences. I never read the rest of the books in the series, and I’m glad I didn’t, because I think perhaps one of my favorite aspects of the book -- one of its lessons for even adult authors -- is how it ends, in that it doesn’t quite end, leaves us in the aperture of uncertainty: “Behind him, across the vast distances of space and time, from the place he had left, he thought he heard music too. But perhaps it was only an echo.”

4. Dimitry Elias Léger, author of God Loves Haiti: