Poets know form equals function. Even better, poets know form enables function — which might explain why poets appear more deliberately invested in form than fiction writers. Form is essential to poetry because it requires the union of strangeness and conformity. By nature, poems are acts of selection and deletion. The poet makes her own margins. In fiction, white space is often arbitrary: a clearing of the space amidst dialogue, the breaths between paragraphs. Poems are sculpted art, and it helps to begin them with a sense of form.

Edward Hirsch’s The Essential Poet’s Glossary — what he calls a “shorter and more focused” version of his encyclopedic A Poet’s Glossary — contains a wide variety of entries. He covers poetic movements and styles, from “abstract poetry” to “zaum,” a “kind of sound poetry, a disruptive poetic language focused on the materiality of words.” A gifted poet himself, Hirsch has long been known as a clear and specific critic. Each entry of this pared volume feels like a tight, concrete prose poem. Lovers of verse are blessed with specific examples and quotable lines. Hirsch’s book sends poets to other books, other poems, and even better — inspires poets to create new work.

Edward Hirsch’s The Essential Poet’s Glossary — what he calls a “shorter and more focused” version of his encyclopedic A Poet’s Glossary — contains a wide variety of entries. He covers poetic movements and styles, from “abstract poetry” to “zaum,” a “kind of sound poetry, a disruptive poetic language focused on the materiality of words.” A gifted poet himself, Hirsch has long been known as a clear and specific critic. Each entry of this pared volume feels like a tight, concrete prose poem. Lovers of verse are blessed with specific examples and quotable lines. Hirsch’s book sends poets to other books, other poems, and even better — inspires poets to create new work.

My favorite part of Hirsch’s book is his compendium of poetic forms. Many are idiosyncratic and obscure — adjectives that have never stopped poets before. Each poetic form is an opportunity. A new house for words. In alphabetical order, here are 10 of the most intriguing forms included in Hirsch’s volume. Why not try them yourself?

1. Canzone

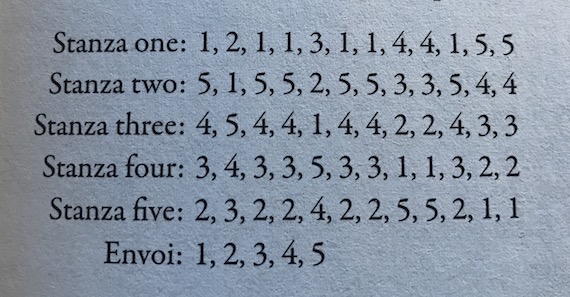

Petrarch established this form of lyric love poem with stanzas of five or six lines, ending with an envoi — a half-stanza. Hirsch identifies Dante Alighieri as an admirer of the canzone, and the great poet created his own “maddeningly difficult” permutation of the form, which “uses the same five end-words in each of the five 12-line stanzas, intricately varying the pattern.”

See also the recursive wit of Marilyn Hacker’s “Canzone:” “sinewy and singular, the tongue / accomplishes what, perhaps, no other organ / can.”

2. Epinicion

Pindar began the tradition of writing commissioned victory odes for 5th -century B.C.E. athletes. These poems “called for an ecstatic performance that communally reenacted the ritual participation in the divine.” A race or a wrestling match became the occasion for eternal significance. Gods and heroes were intoned. Steph Curry and Serena Williams deserve contemporary epinicia, but so might weekend warriors on the pick-up court hustling to recreate glory days. It would not be the first time that poetry has elevated the mediocre.

3. Ghazal

A gorgeous form, originated in 7th-century Arabia and practiced until the present. Hirsch finds meaning in both definitions of the word: “sweet talk” and “the cry of the gazelle when it is cornered in a hunt and knows it must die.” Ahmed Ali notes an “atmosphere of sadness and grief pervades the ghazal.” Agha Shahid Ali calls them “ravishing disunities.” The form has several versions, but in one, there are “five or more autonomous couplets. Each two-line unit is independent, disjunctive.” See Patricia Smith’s “Hip-Hop Ghazal:” “As the jukebox teases, watch my sistas throat the heartbreak, / inhaling bassline, cracking backbone and singing thru hips.”

4. Kyrielle

A French form with “any number of four-line stanzas, usually rhymed. The last line of the first stanza repeats, sometimes with meaningful variations, as the final line of each quatrain.” Hirsch suggests Thomas Campion’s 1613 poem “With broken heart and contrite sigh” as a text that “fits the letter and law” of the form. Campion repeats “God, be merciful to me” before concluding “God has been merciful to me.” Another useful example: Theodore Roethke’s children’s poem “Dinky:” “O what’s the weather in a Beard? / It’s windy there, and rather weird, / And when you think the sky has cleared / — Why, there is Dirty Dinky.”

5. Muwashshah

Andalusian Arabic strophic poem that “regularly alternates sections with separate rhymes and others with common rhymes.” Think aa bbaa ccaa and so on. Began in 9th-century Spain and delivered in classical Arabic — although its final couplet often arrived in more vernacular Spanish. Later, Jewish Andalusian poets adopted the form, which became known as “girdle poems.” Peter Cole describes such a poem as one “in which the rhyming chorus winds about the various strophes of the poem as a gem-studded sash cuts across the body.”

6. Pantoum

So much in poetry is lost in translation, including the strict original rhyme of Charles Baudelaire’s pantoum “Evening Harmony:” “Now comes the time when swaying on its stem / each flower offers incense to the night; / phrases and fragrances circle in the dark– / languorous waltz that casts a lingering spell!” The spirit remains. Each line of a pantoum includes between eight and 12 syllables. Hirsch likens the pantoum’s disjunctive nature to the ghazal: “the sentence that makes up the first pair of lines has no immediate logical or narrative connection with the second pair of lines.” At first, the connection is made by rhyme, sound repetition, or even pun, but “there is also an oblique but necessary relationship, and the first statement turns out to be a metaphor for the second one.” The pantoum “is always looking back over its shoulder, and thus is well suited to evoke a sense of times past.”

7. Renga

A Japanese form, meaning “linked poem.” First created “around a thousand years ago” as a “party game,” each stanza of a renga links to the preceding section. Poets bounced tanka-like sections off each other, honing “their skills at creating images and linking dissimilar elements.” In the traditional Japanese method, the composition begins with an honored guest writing the opening, followed by an accompaniment by the party’s host. Certain renga shifted from playful to serious, but those light-hearted poetic games still remain.

8. Tenson

In the 12th century, Provençal poets debated in verse battles. Each tenson “could take any metrical form, through the respondent was often challenged to reply in the same meter and rhyme scene used by the challenger.” If no literal combatant existed, poets sometimes created imaginary enemies. Yet contemporary poets likely would have no problem finding literary adversaries, and they could follow the model of Dante Alighieri and “his one-time friend Forese Donati,” who exchanged “six rancorous and insulting sonnets.”

9. Triolet

Eight-lined poem, with two rhymes and two refrains. The subject is introduced in the first two lines. The fourth line is repeated later; between those repetitions include lines that expand the original subject. The final lines “knit the conclusion.” Repeated lines evolve in meaning and connotation. Hirsch describes the form as “intricate, playful, and melodious,” — but notes the first English triolets were prayers by 17th-century Benedictine monk Patrick Carey. According to Edmund Gosse, “nothing can be more ingeniously mischievous, more playfully sly, than this tiny trill of epigrammatic melody, turning so simply on its own innocent axis.” Innocent, yes, but also sharp, as in the pen of Sandra McPherson: “She was in love with the same danger / everybody is. Dangerous / as it is to love a stranger, / she was in love.”

10. Villanelle

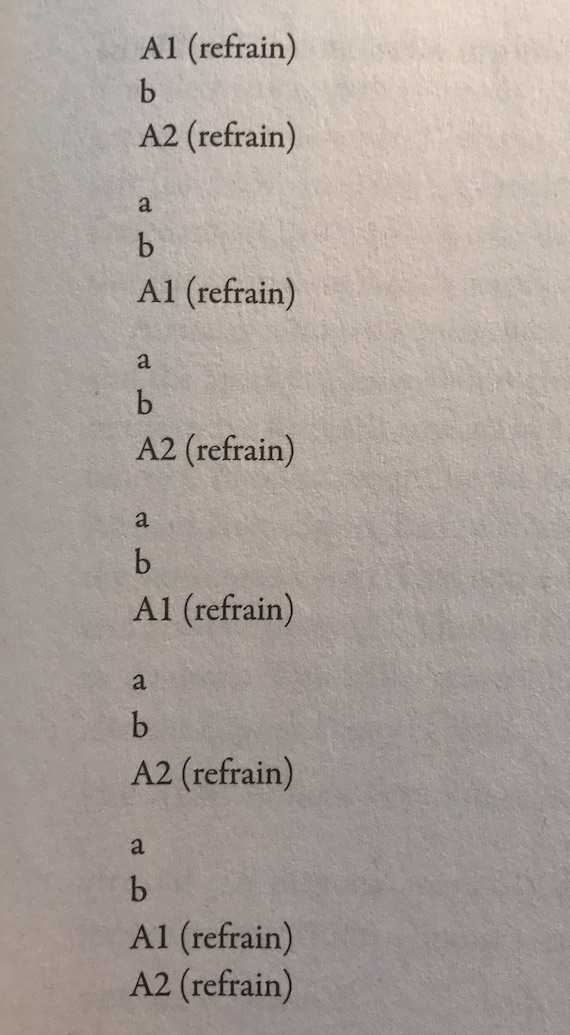

Hirsch includes common and tried forms like sonnets, and although I’ve leaned toward the more unique forms, I can’t ignore the beautiful appeal of the villanelle, a true test of poetic endurance and dexterity (one that tempted and strained Stephen Dedalus). A French form by way of Italian pastoral folk songs, the villanelle contains “nineteen lines divided into six stanza — five tercets and one quatrain.” The rhyme and repetition is as follows:

Elizabeth Bishop and other poets have realized the “compulsive returns” of the villanelle form speak to loss: “The art of losing isn’t hard to master.” Others, like Aimee Nezhukumatathil, have spun the form into fresh designs, as in “After the Auction, I Bid You Good-Bye:” “You elbow me with your corduroy jacket / when a box chock-full of antique marbles comes up. / I can’t hear your whispers above the auctioneer’s racket. / / The clipped speech of the auctioneer cracked / me up when you impersonated him in bed.” The best poets spring headlong into forms, and, faced with forced constraints and concision, make all things new.