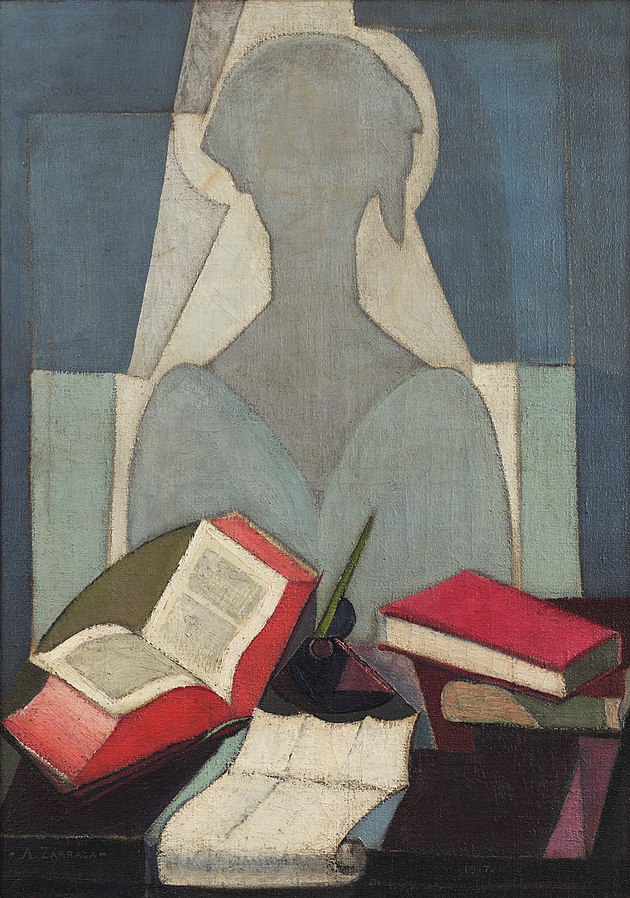

As a bookish only child who came of age in the ’90s, I got ideas about how I might become lovely—and as a result, I hoped, passionately loved—not from the style sites, beauty blogs, YouTube tutorials, Instagram videos, and Pinterest pages that are now ubiquitous, but from the novels and stories in which my nose was perpetually buried. My innate interest in beauty—spiritual, sartorial, skinwise, and otherwise—was stoked by 20th-century literature and the captivating female characters who populate it. Books I read between the spongy ages of 12 and 20 were especially potent. They inspired me to become a writer and invent fictional characters of my own, but I didn’t only long to write; I also longed to be written, like the heroines of these books—to be regarded with the kind of affection, interest, and attention to detail that infuses so many of the satisfying sentences their authors used to describe them. Inevitably, many of my choices and rituals concerning beauty and adornment, several of which persist, resulted from the images that bloomed in my imagination while I read.

In junior high, my hair—thanks to hormonal changes, no doubt—transformed of its own accord from fairly straight to extravagantly curly. I struggled to accept the sudden ringlets, which required an entirely new way of washing, combing, and styling. I also agonized over what I was sure was the near-fluorescent ruddiness of my cheeks; it betrayed, I thought, the awkward bashfulness with which I was often battling, and I tried to mask it with powder as soon as I was allowed to wear a bit of makeup. Then I met Ántonia Shimerda, the 14-year-old Bohemian immigrant to Nebraska in Willa Cather’s My Ántonia. She was a character whose vitality, spirit, and earthiness I admired. And she had curly hair. And red cheeks. Ántonia’s “curly and wild-looking” locks make an ideal if temporary dwelling for a grasshopper she brings home to show her father. She “carefully put the green insect in her hair,” Cather writes, “tying her big handkerchief down loosely over her curls…,” and her cheeks “had a glow of rich, dark color” that Cather likens to “red plums.” Because of Ántonia, who was a role model of mine due to the indomitable strength of her personality and warmth of her heart, I embraced my curls and put down the face powder.

In junior high, my hair—thanks to hormonal changes, no doubt—transformed of its own accord from fairly straight to extravagantly curly. I struggled to accept the sudden ringlets, which required an entirely new way of washing, combing, and styling. I also agonized over what I was sure was the near-fluorescent ruddiness of my cheeks; it betrayed, I thought, the awkward bashfulness with which I was often battling, and I tried to mask it with powder as soon as I was allowed to wear a bit of makeup. Then I met Ántonia Shimerda, the 14-year-old Bohemian immigrant to Nebraska in Willa Cather’s My Ántonia. She was a character whose vitality, spirit, and earthiness I admired. And she had curly hair. And red cheeks. Ántonia’s “curly and wild-looking” locks make an ideal if temporary dwelling for a grasshopper she brings home to show her father. She “carefully put the green insect in her hair,” Cather writes, “tying her big handkerchief down loosely over her curls…,” and her cheeks “had a glow of rich, dark color” that Cather likens to “red plums.” Because of Ántonia, who was a role model of mine due to the indomitable strength of her personality and warmth of her heart, I embraced my curls and put down the face powder.

Eschewing makeup, however, demands vigilant skin care, and I’m grateful for potions that lend the face a lit-up look. One of Leopold Bloom’s errands on the eventful day of June 16th in the first part of James Joyce’s Ulysses is to have the neighborhood chemist make up a batch of the face lotion favored by his lush wife, Molly. Bloom marvels at the quality of Molly’s skin, which he deems “so delicate, like white wax.” At the chemist’s, he recites most of the lotion’s ingredients—”Sweet almond oil and tincture of benzoin…and then orangeflower water…and white wax also”—so I’ve been able to concoct an approximation at home with supplies sourced from the local health food store. Playing apothecary is fun, and I share Bloom’s sentiment that “homely recipes are often the best: strawberries for the teeth: nettles and rainwater: oatmeal they say steeped in buttermilk. Skinfood.”

Eschewing makeup, however, demands vigilant skin care, and I’m grateful for potions that lend the face a lit-up look. One of Leopold Bloom’s errands on the eventful day of June 16th in the first part of James Joyce’s Ulysses is to have the neighborhood chemist make up a batch of the face lotion favored by his lush wife, Molly. Bloom marvels at the quality of Molly’s skin, which he deems “so delicate, like white wax.” At the chemist’s, he recites most of the lotion’s ingredients—”Sweet almond oil and tincture of benzoin…and then orangeflower water…and white wax also”—so I’ve been able to concoct an approximation at home with supplies sourced from the local health food store. Playing apothecary is fun, and I share Bloom’s sentiment that “homely recipes are often the best: strawberries for the teeth: nettles and rainwater: oatmeal they say steeped in buttermilk. Skinfood.”

Of course fastidiousness is crucial to both inner and outer beauty, and the skin of one’s body must not be forgotten in the effort to maintain a luminous face. Following in the footprints of the ever-fresh Komako, the lonesome young woman living at a hot springs resort town in the mountains of Japan in Yasunari Kawabata’s Snow Country, I take frequent baths. Komako always seems to be coming from or heading to the bath: “[T]he impression she gave was above all one of cleanliness,” Kawabata writes. “Every day she had a bath in the hot spring, famous for its lingering warmth.” While my own bathwater doesn’t spurt from a mineral-rich spring, it’s usually infused with what I hope are similarly healing salts, plus drops of pine oil to evoke the conifers of Kawabata’s icy landscape. Just as I imagine Komako does, I like to do plenty of scrubbing to detoxify and promote good circulation.

Of course fastidiousness is crucial to both inner and outer beauty, and the skin of one’s body must not be forgotten in the effort to maintain a luminous face. Following in the footprints of the ever-fresh Komako, the lonesome young woman living at a hot springs resort town in the mountains of Japan in Yasunari Kawabata’s Snow Country, I take frequent baths. Komako always seems to be coming from or heading to the bath: “[T]he impression she gave was above all one of cleanliness,” Kawabata writes. “Every day she had a bath in the hot spring, famous for its lingering warmth.” While my own bathwater doesn’t spurt from a mineral-rich spring, it’s usually infused with what I hope are similarly healing salts, plus drops of pine oil to evoke the conifers of Kawabata’s icy landscape. Just as I imagine Komako does, I like to do plenty of scrubbing to detoxify and promote good circulation.

Nicole Diver, the charismatic blonde with a sad secret in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Tender Is the Night, also takes a bath before beginning a love affair that will shift the trajectory of her life. “She bathed and anointed herself and covered her body with a layer of powder, while her toes crunched another pile on a bath towel…She put on the first ankle-length day dress that she had owned for many years, and crossed herself reverently with Chanel Sixteen.” This passage not only impressed upon me the degree to which literature can provoke an exquisite sensory experience, but also the importance of perfume application as an everyday ceremonial rite. Fitzgerald invented Chanel Sixteen—there never was such a thing—but the first fragrance I bought for myself was a Chanel, the softly shimmering eau de toilette version of No. 5. Then I caught it: the perfume bug, an ongoing fascination with odor as a kind of olfactory language that both makes and unearths memories. My obsession has not only inspired me to write a book’s worth of as-yet unpublished perfume essays, each one devoted to a different scent, but has also driven me quite happily from costly bottles of obscure niche fragrances to tiny vials of cheap but pleasing oils and everywhere in between. I don’t discriminate. I just want to smell like someone about whom stories could be written.

Nicole Diver, the charismatic blonde with a sad secret in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Tender Is the Night, also takes a bath before beginning a love affair that will shift the trajectory of her life. “She bathed and anointed herself and covered her body with a layer of powder, while her toes crunched another pile on a bath towel…She put on the first ankle-length day dress that she had owned for many years, and crossed herself reverently with Chanel Sixteen.” This passage not only impressed upon me the degree to which literature can provoke an exquisite sensory experience, but also the importance of perfume application as an everyday ceremonial rite. Fitzgerald invented Chanel Sixteen—there never was such a thing—but the first fragrance I bought for myself was a Chanel, the softly shimmering eau de toilette version of No. 5. Then I caught it: the perfume bug, an ongoing fascination with odor as a kind of olfactory language that both makes and unearths memories. My obsession has not only inspired me to write a book’s worth of as-yet unpublished perfume essays, each one devoted to a different scent, but has also driven me quite happily from costly bottles of obscure niche fragrances to tiny vials of cheap but pleasing oils and everywhere in between. I don’t discriminate. I just want to smell like someone about whom stories could be written.

After bathing comes dressing. In D.H. Lawrence’s Women in Love, the cooler of the two titular women, Gudrun, is an artist blessed with an enviable sang-froid that remains unruffled even when she is catcalled by local miners—”What price the stockings?”—while stepping out in her signature boldly-colored tights. She has them in a kaleidoscopic array of shades and fabrics: “…grass-green stockings…pink silk stockings…woolen yellow stockings…” Because of Gudrun, I went through a brightly-tinted-tights phase, partly because of the aesthetic pleasure it gave me, and partly because I wanted some of her blithe attitude to seep into mine, though in actuality I was much more like her hypersensitive sister, Ursula, who dons no stockings of remarkable color but instead has practically got her heart sewn onto her sleeve.

After bathing comes dressing. In D.H. Lawrence’s Women in Love, the cooler of the two titular women, Gudrun, is an artist blessed with an enviable sang-froid that remains unruffled even when she is catcalled by local miners—”What price the stockings?”—while stepping out in her signature boldly-colored tights. She has them in a kaleidoscopic array of shades and fabrics: “…grass-green stockings…pink silk stockings…woolen yellow stockings…” Because of Gudrun, I went through a brightly-tinted-tights phase, partly because of the aesthetic pleasure it gave me, and partly because I wanted some of her blithe attitude to seep into mine, though in actuality I was much more like her hypersensitive sister, Ursula, who dons no stockings of remarkable color but instead has practically got her heart sewn onto her sleeve.

Little finishing touches that complete a look come in many forms, including nail polish—an adornment about which I’ve always had mixed feelings. I sometimes put it on, but invariably remove it within hours. I love it on others the same way I love other people’s tattoos, but on me it feels somehow wrong, artificial. Maybe it makes me uneasy because I can’t help but associate it with Muriel, the shallow wife of the brilliant and sensitive seer, Seymour Glass, who figures in J.D. Salinger’s “A Perfect Day for Bananafish” and other stories. When Muriel first appears, she is in the process of “putting lacquer on the nails of her left hand.” Growing up, I—like his younger siblings Franny and Zooey—was heavily influenced by and devoted to Seymour, and it was clear the hopelessly mainstream Muriel just didn’t get him. “With her little lacquer brush…she went over the nail of her little finger, accentuating the line of the moon. She then replaced the cap on the bottle of lacquer and, standing up, passed her left—the wet—hand back and forth through the air.” This insouciant gesture seemed to embody all the spiritual poverty and bourgeois materialism of which I was sure Muriel was guilty.

Other finishing touches, however, feel the opposite of artificial, but rather like external reflections of one’s inner self. I’m never without my two little gold bracelets—one on each wrist. There is something about adorning my wrists—the gateways to my hands—in this way that makes sense. I like to write and make jewelry; my hands accomplish the tasks at the heart of my life. But I first got the idea to do this while reading my favorite of Jack Kerouac’s novels, the autobiographical chronicle of once-in-a-lifetime adolescent love, Maggie Cassidy. The book’s title character accessorizes similarly. “Tonight,” Kerouac writes of Maggie, “she is more beautiful than ever, she has…little bracelets on both wrists; hands crossed, sweet white fingers I eye with immortal longing to hold in mine…”

Other finishing touches, however, feel the opposite of artificial, but rather like external reflections of one’s inner self. I’m never without my two little gold bracelets—one on each wrist. There is something about adorning my wrists—the gateways to my hands—in this way that makes sense. I like to write and make jewelry; my hands accomplish the tasks at the heart of my life. But I first got the idea to do this while reading my favorite of Jack Kerouac’s novels, the autobiographical chronicle of once-in-a-lifetime adolescent love, Maggie Cassidy. The book’s title character accessorizes similarly. “Tonight,” Kerouac writes of Maggie, “she is more beautiful than ever, she has…little bracelets on both wrists; hands crossed, sweet white fingers I eye with immortal longing to hold in mine…”

I may feel complete with the bracelets, but there’s also sometimes a vaguely nagging sense of unfinished business: like many women, my thoughts often return to my hair, as they did in junior high. I may maintain its natural coiled texture, but what about the color? It’s a question over which I’m lately mulling, especially now that I’ve spotted and plucked a number of silvery strands. So far, though, I’ve done nothing about it. In Thomas Hardy’s The Return of the Native, witchy Eustacia Vye, fondly dubbed “Queen of Night” by Hardy, is a loner desperate for adventures beyond the bleak heath where she lives. She has inky hair—as dark as her eventual mood. “To see her hair,” Hardy writes, “was to fancy that a whole winter did not contain darkness enough to form its shadow.” The romantic portrait is partly why in the era of ombré, “sombre,” “tortoiseshell,” lowlights, “babylights,” and all the other enticing iterations of highlights, I continue to choose, sometimes uneasily, to let my locks remain their natural nearly-black hue.

I may feel complete with the bracelets, but there’s also sometimes a vaguely nagging sense of unfinished business: like many women, my thoughts often return to my hair, as they did in junior high. I may maintain its natural coiled texture, but what about the color? It’s a question over which I’m lately mulling, especially now that I’ve spotted and plucked a number of silvery strands. So far, though, I’ve done nothing about it. In Thomas Hardy’s The Return of the Native, witchy Eustacia Vye, fondly dubbed “Queen of Night” by Hardy, is a loner desperate for adventures beyond the bleak heath where she lives. She has inky hair—as dark as her eventual mood. “To see her hair,” Hardy writes, “was to fancy that a whole winter did not contain darkness enough to form its shadow.” The romantic portrait is partly why in the era of ombré, “sombre,” “tortoiseshell,” lowlights, “babylights,” and all the other enticing iterations of highlights, I continue to choose, sometimes uneasily, to let my locks remain their natural nearly-black hue.

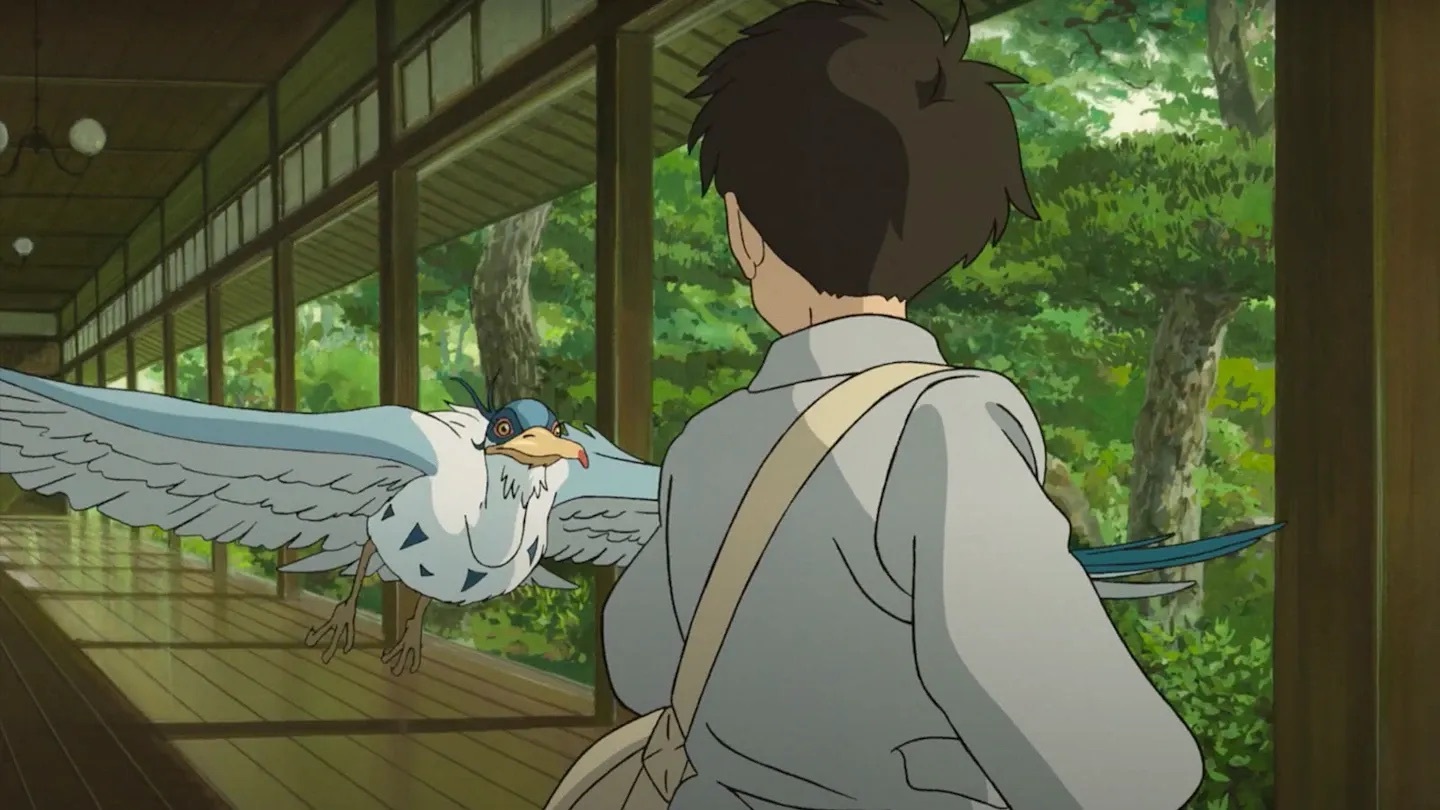

Consequently, not too long ago, an author of short stories and novels thrilled the bookish girl in me when he whispered that my hair was “so dark a seagull would love to die in it.” Oil-dark was what he meant. His statement, too, was dark—humorous, singularly strange and sweet, a compliment only a writer could give. For a few moments, I felt a little like a woman inside a novel. He answered the longing I’d felt when I first fell under the spell of fascinating feminine figures bound between pages and rendered only with words. I was no longer exclusively the reader or the writer; sometimes, I would be the one who is written, the one who is read.

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons.