Maybe we should scrap “minimalism” as part of the literary taxonomy. Generally taken, it refers to a type of short story in which the style is succinct, suggestive and unsentimental. The movement reached critical mass in the 1980s and early ’90s, due largely to the editorial stewardship of Gordon Lish. Today we consider Raymond Carver our minimalist lodestar, though shining around him are Amy Hempel and Mary Robison, as well as the earlier work of Frederick Barthelme, Ann Beattie and Richard Ford.

As a club, however, these writers never asked to wear the minimalist badge. Carver rejected the term, preferring, as Tess Gallagher writes in her introduction to Carver Country, “the more accurate identification of his style as that of a ‘precisionist.’” And Robison, in a 2001 interview with BOMB, also rebuffed the label. “I detested it,” she says. “Subtractionist, I preferred. That at least implied a little effort. Minimalists sounded like we had tiny vocabularies and few ways to use the few words we knew. I thought the term was demeaning; reductive, clouded, misleading, lazily borrowed from painting.”

As a club, however, these writers never asked to wear the minimalist badge. Carver rejected the term, preferring, as Tess Gallagher writes in her introduction to Carver Country, “the more accurate identification of his style as that of a ‘precisionist.’” And Robison, in a 2001 interview with BOMB, also rebuffed the label. “I detested it,” she says. “Subtractionist, I preferred. That at least implied a little effort. Minimalists sounded like we had tiny vocabularies and few ways to use the few words we knew. I thought the term was demeaning; reductive, clouded, misleading, lazily borrowed from painting.”

Regardless, “minimalism” has stuck as a literary descriptor. Its ethos contends that dramatic power can be achieved through intensity. That is, it’s not just the chemicals that produce an explosion, but how tightly they’re compressed. This idea of compression, however, seems a hallmark of all powerful writing. Story writers of all stripes achieve dramatic effect by reducing exposition, eliding superfluous detail, rejecting peripheral plot points. That’s what keeps their stories short; thus, all writers of short fiction are, if not minimalists, miniaturists.

In regards to narrative, the stories considered minimalist often begin in medias res; they often focus intently on a single scene, time frame or physical setting; and they often eschew the traditional arc of conflict, complication, climax. So tightly wound, these stories can at times seem claustrophobic, leaving a reader gasping for air in pockets of subtext. To sustain such a narrative over the course of a longer work, like a novel, seems a grand ambition.

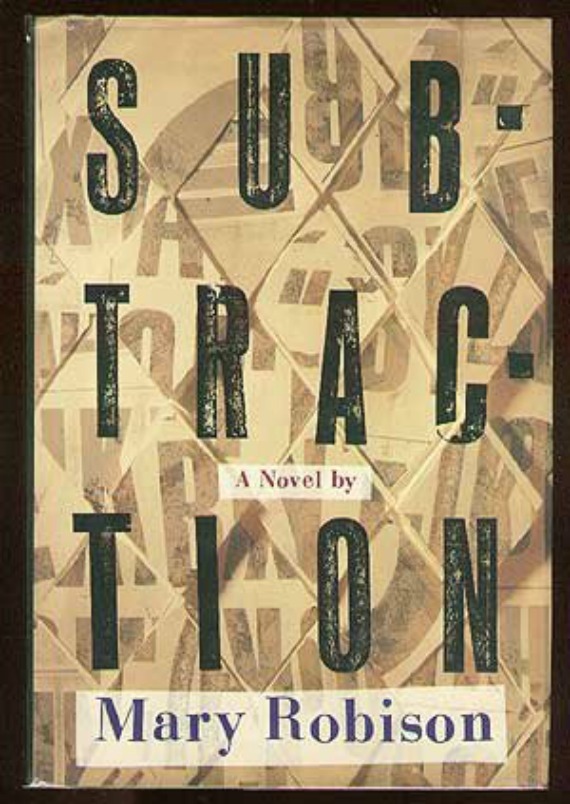

Which brings me to Mary Robison’s Subtraction. Her second novel, it was published in 1991 to mixed reviews. While one reviewer stated that “Robison raises sitcom wit to the level of real emotional situations, real comedy and real art,” another concluded, “Subtraction does not manage to add up to much at all.” Alas, the novel never appeared in paperback. Today, however, 25 years after its release, Subtraction stands out as a high-wire act of the novel form — taut in expression yet rich with humanity, expertly crafted and unfairly neglected.

Which brings me to Mary Robison’s Subtraction. Her second novel, it was published in 1991 to mixed reviews. While one reviewer stated that “Robison raises sitcom wit to the level of real emotional situations, real comedy and real art,” another concluded, “Subtraction does not manage to add up to much at all.” Alas, the novel never appeared in paperback. Today, however, 25 years after its release, Subtraction stands out as a high-wire act of the novel form — taut in expression yet rich with humanity, expertly crafted and unfairly neglected.

Subtraction is narrated by Paige, a poet and Harvard professor in pursuit of her husband, Raf, a blackout drunk who’s disappeared from their home in Brookline. As the novel begins, Paige tracks Raf to Houston and they rent a house while Raf attempts sobriety. They’re joined by Raymond, himself a recovering alcoholic, and Pru, a free-thinking exotic dancer. Things go well until Raf falls off the wagon — falls, as Paige says, “off the earth.”

The term “subtraction” suggests Robison’s narrative, thematic and stylistic concerns. First, it refers to the desertion of a romantic partner and the diminishment of memory from alcoholic blackout. Next, it alludes to the depreciation of self that attends a broken relationship. But perhaps most importantly, “subtraction” describes Robison’s lean, selective prose style. Over the course of 215 pages it’s perfected, endowing the narrative with subtle comedy and electric tension. Not long after Raf disappears again halfway through the novel, Paige receives an enigmatic postcard:

Paige,

They ought to change the fucking symbol for infinity. Instead of an eight on its side, it should be 0 – Zero (Nothing).

Its postmark leads Paige back to Massachusetts on the heels of a nor’easter. There she finds a note tacked to the door of her and Raf’s Brookline house, in which Raf explains his situation — he’s been eluding “the poleeze” and now “I got to go away for three days or a week” — and proposes he and Paige reunite shortly at Paige’s mom’s seaside resort. Thus the suspense that propels the final quarter of the novel: How determined is Raf? Determined enough to overcome his demons as well as the encroaching, historic blizzard? A reader is led to conclude that if he and Paige can reconcile, it will be an ultimate show of love, compassion, redemption.

Subtraction seems uniquely successful in its construction of sympathetic characters. Admittedly, minimalistic stories, in their quest for economy, often reduce characters to types. But in the expanse of Robison’s novel, these characters are allowed to show their complexity. Raf’s a cad, sure, but he’s also a former foundry worker, smoke jumper and lobsterman, Princeton alumnus and Rhodes scholar. After he sets up a borrowed keyboard on his lap and eases “into intense musical scores,” Paige says, “I never knew you could play… You are the mystery man” — this after five years of marriage!

Had all Raf’s attributes been provided in plain old exposition, they might seem implausible. But as they occur organically over many scenes, they show Raf as charismatic, dynamic, magnetic. He’s intense, and he evokes intensity in others. That’s not to say Paige is as intoxicated with him as he is with booze; often the rope of her patience seems worn to its final thread. The two of them feel no institutional obligation to marriage, but rather a karmic, psychic connection. At its core, Subtraction is a romantic novel.

And it’s an immersive novel, its settings vivid and even its bit players distinct. The verbs astound with their precision: a car “jounces” over train tracks, Paige “drips” change into a soda machine, Raf “flumps” an armload of paperbacks onto a counter. Robison is most concerned with the immediate — the moment itself, its textures, its dramatic foreground. Her characters are observant, intelligent and honest. They possess wit free from both ennui and condescension. Each line of dialogue rings with familiarity, each gesture with intimacy.

Early in Subtraction, Paige lingers beside the pool of her Houston hotel, eavesdropping on a group of foreign scholars. Their conversation turns from film, to the origin of ideas, to the creation of art: “‘Selection, no?’ someone said. ‘What it means to be an artist.’”

So call it what you will: “minimalism,” “precisionism,” “subtractionism,” even “selectionism.” Let’s forget the -isms. In Subtraction Mary Robison creates a poignant, forceful tale of lovers in limbo. Her writing is rich with detail, lean with implication. When the tedium, the drudgery, the ephemera are sifted out, we’re left with the intense. Each word pulls its weight. Nothing is wasted.