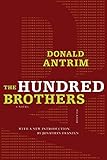

Donald Antrim is perhaps the master of the novel in which men are crammed into confined spaces — a group of psychotherapists in a pancake joint (The Verificationist) or 100 brothers in a library (The Hundred Brothers). Chris Bachelder contributes a gem to the genre with The Throwback Special, in which a football team’s worth of men descend upon a hotel to conduct an annual ritual based on a football game that occurred 30 years ago.

The men loiter in “concentric arcs” around the hotel’s lobby fountain as they wait to check in, “not unlike the standard model of the atom;” they gather to eat pizza in a cramped room smelling of “sweet tomato sauce and warm meat;” and when they find another group of hotel guests descending on the continental breakfast station, they “[lurk] at the boundaries of the dining area, anxious about resources.” All this clustering is a prelude to the formation of a football huddle, “a perfect and intimate order, elemental and domestic, like a log cabin in the wilderness…they could perhaps sense in the huddle the origins of civilization.” (Zog, you go deep while Durc and Plarf sneak up on the mammoth from the blind side.)

The men loiter in “concentric arcs” around the hotel’s lobby fountain as they wait to check in, “not unlike the standard model of the atom;” they gather to eat pizza in a cramped room smelling of “sweet tomato sauce and warm meat;” and when they find another group of hotel guests descending on the continental breakfast station, they “[lurk] at the boundaries of the dining area, anxious about resources.” All this clustering is a prelude to the formation of a football huddle, “a perfect and intimate order, elemental and domestic, like a log cabin in the wilderness…they could perhaps sense in the huddle the origins of civilization.” (Zog, you go deep while Durc and Plarf sneak up on the mammoth from the blind side.)

Bachelder’s portrait of middle-class, middle-aged males revolves around football, in which we find a unique combination of brute force, obsessive strategic organization, and improvisation. Full disclosure: In my version of hell, scowling football coaches pace up and down the River Styx, their steady barking of martial commands only interrupted to consult their laminated sheets on which every possible variation on the off-tackle running play is written. My distaste for the sport’s phony militarism notwithstanding, Bachelder’s “football” novel is an eerie, witty work dissecting a modern-day sacrificial (sack-rificial?) ritual. Though the curious rite described herein takes place in a “two-and-a-half-star chain” hotel off of I-95, it taps into our ancestral roots; the novel’s epigraph is taken from Johan Huizinga’s Homo Ludens, a treatise on the “primacy” and “sacred earnestness” of play across cultures.

The group of men meet to recreate a famously disastrous, and violent, football play. (Bachelder’s first novel, Bear v. Shark, was structured around a more absurdist agon.) During a 1985 game against the New York Giants, the Washington Redskins attempted a flea flicker — quarterback hands ball to running back, running back tosses ball back to quarterback, who looks to pass the ball downfield. The trick was clumsily executed, the defense wasn’t fooled, and quarterback Joe Theismann was carted off with a career-ending compound fracture courtesy of the Giants’ Lawrence Taylor, the fearsome outside linebacker who seemed shaken by the bone-crushing damage he has inflicted. The TV commentator Frank Gifford warns his audience before cutting to the replay: “And I’ll suggest if your stomach is weak, just don’t watch.”

The group of men meet to recreate a famously disastrous, and violent, football play. (Bachelder’s first novel, Bear v. Shark, was structured around a more absurdist agon.) During a 1985 game against the New York Giants, the Washington Redskins attempted a flea flicker — quarterback hands ball to running back, running back tosses ball back to quarterback, who looks to pass the ball downfield. The trick was clumsily executed, the defense wasn’t fooled, and quarterback Joe Theismann was carted off with a career-ending compound fracture courtesy of the Giants’ Lawrence Taylor, the fearsome outside linebacker who seemed shaken by the bone-crushing damage he has inflicted. The TV commentator Frank Gifford warns his audience before cutting to the replay: “And I’ll suggest if your stomach is weak, just don’t watch.”

These men did watch as boys, and something about the play’s cataclysmic failure, the collapse of the best-laid plans of mice and offensive coordinators, lodged in their adolescent psyches. The novel opens on the 16th year of the men reenacting the snap. We don’t find out how these performers, who lead relatively humdrum lives devoid spectacular drama, established the group or found each other; illuminating the society’s origins, it seems, would dampen its mystery. The men are not really friends; socialization is confined to the reenactment weekend. Some of their familial or professional troubles are recounted, and Bachelder does flit in and out of their psyches, but in general the men, partly because there are so many of them, remain purposefully flat. It is the ritual that matters — the men’s role in it and their behavior leading up to it. The description of one man breaking in his new mouthguard tells you everything you need to know about him.

At times, The Throwback Special has the feel of Tom McCarthy’s Remainder, which itself explores the transporting thrill of re-creation. This pleasure lies in the chance to asymptotically “approach perfection” by getting closer and closer to the historical model; or in submitting to the play’s “choreography of chaos and ruin;” or in the suspense that all great drama, even when we know the outcome, generates: “He had liked the sense that anything at all might happen, even though only one thing could happen.”

At times, The Throwback Special has the feel of Tom McCarthy’s Remainder, which itself explores the transporting thrill of re-creation. This pleasure lies in the chance to asymptotically “approach perfection” by getting closer and closer to the historical model; or in submitting to the play’s “choreography of chaos and ruin;” or in the suspense that all great drama, even when we know the outcome, generates: “He had liked the sense that anything at all might happen, even though only one thing could happen.”

A blend of comfort and tension lies at the heart of this ritual, faith in its power and anxiety about its stability. In Homo Ludens, Huizinga mentions the fragility of play, the ease with which its sustaining illusion can be shattered or its cordoned-off space violated. Though the men have at it for nearly two decades, one worrywart has the “anxious sensation that the ritual, seemingly so entrenched, was in fact precarious.” The conference room in which they usually conduct the lottery has been usurped by a vaguely-named company, Prestige Vista Solutions. (“They just despoil the environment and establish tax havens and seize conference rooms,” gripes one of the deposed reenactors.) The hotel fountain is initially dry. A jersey, and a player, is missing. There are murmurs that this will be the last year, which opens up the “ancient wound of seclusion” in some of the more insecure men. Each wrinkle contributes to a disturbing sense of impermanence, the fear that the mythic ceremony they have devised is not eternal.

One of the most interesting aspects of the novel is how the ritual at once reveals and promises to assuage male neuroses. Nowhere is this more evident than in the lottery scene, in which the men draw lottery numbers from a giant drum to determine the order in which they will select their roles. Bachelder shrewdly anatomizes the various psychological types: those who find “nobility in ruinous failure” tend to choose a Washington player who is “essential to the calamity,” a member of the crumbling offensive line for example; others are drawn to the Washington offense “out of a keen, if unrecognized, identification with disappointment and culpability and bumbling malfunction;” the “aesthetes” opt for players based on some aspect of some sartorial accessory or distinctive posture; men who “craved the familiar comfort of anonymity and insignificance” yearn to play an insignificant role in the recreation — a retreating Giants cornerback for instance — but “overcompensate for their shameful desire by choosing the most significant player available.”

Regardless of one’s temperament or build, it would be almost sacrilegious not to pick Lawrence Taylor first. Derek, the one black man in the group, simultaneously yearns for and dreads the prospect of winning this first selection, which would force him to “[wade] into the psycho-racial thicket” of picking the star linebacker. In past reenactments, men have played him as a “with a kind of wild-eyed, watch-your-daughters primitivism,” profiting from the reenactment to indulge in a “transgressive racial thrill ride.” Derek wonders how his pick will be interpreted by the other men, and whether or not he could change things by adding some depth to the character:

Selecting Taylor — it was so clear — would not be an opportunity for racial healing and gentle instruction, but an outright act of hostility and aggression. He, Derek, would not control the meaning and significance of Lawrence Taylor’s sack. Centuries of American history would control the meaning and significance of Taylor’s sack.

(That one of the teams still clings to its offensive name adds another element to the “charged racial allegory.”) Derek’s ethical dilemma vanishes when another man wins the first pick and selects L.T., “beating his chest with his fists” and thereby signaling the kind of nuanced portrayal he is likely to produce.

Taylor’s partner and antagonist in the consummating sack is Joe Theismann: “By tradition the man playing Theismann and the man playing Taylor stayed away from each other, like a bride and groom before a wedding.” While failing to pick Taylor would signal weakness, no player is allowed to pick Theismann; the honor falls to the man with the lowest number. The quarterback is a kind of pharmakos, a sacrificial victim at once polluted and holy. While the other men share beds, “it was customary for the man playing Theismann to sleep alone…[a] mildly punitive…form of exile or symbolic estrangement.” Theismann himself, we are told, described his injury in Christ-like terms, his shattered leg bearing the sins of his bumbling linemen; the men who have played him all testify to the intensity of voluntarily offering up themselves to the rushing horde.

Theismann submits to the group’s channeled violence, which is a concentrated form of the scattershot, hostile humor that defines certain kind of male relationship and the “typical masculine joke, a crude homemade weapon that indiscriminately sprayed hostility and insecurity in a 360-degree radius, targeting everyone within hearing range, including the speaker.” One man arrives to the hotel and circles the parking lot in his car, “blasting his horn and shouting community-sustaining threats and maledictions.” This aggressive bantering masks an underlying sincerity: to insult is to love. As Bachelder writes,

…each man…was the plant manager of a sophisticated psychological refinery, capable of converting vast quantities of crude ridicule into tiny, glittering nuggets of sentiment. And vice versa, as necessary.

That this passage happens to refer to the men’s feelings for an inanimate object — the much-maligned lottery drum — makes the men at once more ridiculous and more poignant.

If describing the admittedly silly ritual in such elevated ways seems bombastic, that is partly the point. Serious play depends on a complete adherence to the arbitrary nature of its established rules. Therefore, the reenactment seems puerile to anyone looking in from the outside, including the several Prestige Vista Solutions employees who witness it. These outsiders adopt an ironic stance, but their irony, along with the reader’s, fades when we finally witness the men’s solemn play.