This month marks the 125th anniversary of The Picture of Dorian Gray’s publication. A delicious scandal from the first day it appeared in Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine up to the present, Oscar Wilde’s only novel is so good it has withstood the two deadliest kinds of critical reaction: absolute censure and total adoration. The censure began when a reviewer from the Scots Observer, admitting that Wilde had “brains, art, and style,” venomously dismissed Dorian Gray as a book written only for “outlawed noblemen and perverted telegraph boys.”

That reference to a then-prominent British homosexuality scandal focused the public eye on protagonist Dorian Gray’s relationship with the man who made his portrait, Basil Hallward. In the second edition, Hallward claims to have been “dominated, brain, soul, and power” by Dorian, a sentence that in the Lippincott’s text read “I adored you madly, extravagantly, absurdly.” The implication of a connection between the two men that went beyond the intellectual was not unjustified, and though Wilde prudently played it down in subsequent printings, the damage had been done. Ward, Lock, and Co., Lippincott’s publisher, removed the issue that contained the novel from sale because the press had cried sodomy. Passages from that version were later used to vilify Wilde during his famous indictment for “gross indecency,” a trial that withered his reputation and lead to his irretrievable exile from London.

That reference to a then-prominent British homosexuality scandal focused the public eye on protagonist Dorian Gray’s relationship with the man who made his portrait, Basil Hallward. In the second edition, Hallward claims to have been “dominated, brain, soul, and power” by Dorian, a sentence that in the Lippincott’s text read “I adored you madly, extravagantly, absurdly.” The implication of a connection between the two men that went beyond the intellectual was not unjustified, and though Wilde prudently played it down in subsequent printings, the damage had been done. Ward, Lock, and Co., Lippincott’s publisher, removed the issue that contained the novel from sale because the press had cried sodomy. Passages from that version were later used to vilify Wilde during his famous indictment for “gross indecency,” a trial that withered his reputation and lead to his irretrievable exile from London.

But copies of the book lingered on the shelves of the avant-garde, and when Wilde’s society plays began gathering momentum again after his death, a lavish reprinting of the novel was not far behind. The Picture of Dorian Gray’s trajectory has been upward ever since, and it would amuse Wilde to know that it is now the public who adores him, rather than his detractors, who are committing what he called “the absolutely unpardonable crime of trying to confuse the artist with the subject-matter.” The kisses custodians from Paris’s Père Lachaise Cemetery routinely had to wipe from Wilde’s tomb grew so numerous that in 2011, his estate installed a seven-foot deep plate glass barrier to keep admirers at bay.

I went to the site myself in 2010, when you could still walk up and read the notes Wilde’s fans had left for him. Few referenced his work, but most cast him as a champion of LGBTQ rights. Whether or not he ever played that role, Wilde would be quick to ask what it had to do with the quality of his prose. “There is no such thing as a moral or immoral book,” he wrote in Dorian Gray’s introduction, and the fact that it has survived his moral crucifixion as well as his sainthood is proof that the claim might be true. Think what we will of the man, the book is luminous, terrifying, wonderful.

Understandably, not all critics interested in Wilde’s sexuality are invested in his biography — there is plenty of it in his books. Apart from the impeccable apartments and the clothes, intricate tensions between Eros, art, self-interest, and violence are what make The Picture of Dorian Gray’s great scenes memorable. And the early chapter where Dorian’s portrait is first painted outstrips the rest, because while it blends melodrama and sophistication as well as any scene in William Shakespeare, it also makes the novel a test-kitchen for Wilde’s aesthetic theories.

Wilde wanted to believe that no book could be moral: that to judge art, our sense of good aesthetics (by which he meant unity of form, deep characters, and a roller-coaster plot) should suffice. When he took the stand at his own trial, he asked Victorian London to believe it too. But he took an even bigger risk by allowing the book itself to pose the question. The bravery of The Picture of Dorian Gray is that Wilde was letting his moral and aesthetic theories work out their own implications in his characters. With it, he earned his qualification as a great explorer of the dusky territory between art and ethics.

As Wilde pointed out himself, the portrait-painting scene in chapter two is a modern retelling of Faust, the make-a-deal-with-the-devil scene. Dorian Gray, an arrestingly handsome man of about 20, is having his portrait made by Hallward, one of London’s preeminent artists. In the previous chapter, Hallward begged his friend, the jaded dandy Lord Henry Wotton, not to “spoil” his newfound friendship with Dorian, a man who was bound to “dominate” the rest of his life. Hallward is right to be cautions: Lord Henry is a fast-talker whose only hobby is psychologically “vivisecting” the weaker-minded.

As Wilde pointed out himself, the portrait-painting scene in chapter two is a modern retelling of Faust, the make-a-deal-with-the-devil scene. Dorian Gray, an arrestingly handsome man of about 20, is having his portrait made by Hallward, one of London’s preeminent artists. In the previous chapter, Hallward begged his friend, the jaded dandy Lord Henry Wotton, not to “spoil” his newfound friendship with Dorian, a man who was bound to “dominate” the rest of his life. Hallward is right to be cautions: Lord Henry is a fast-talker whose only hobby is psychologically “vivisecting” the weaker-minded.

As Dorian mounts the dais for the last phase of Hallward’s work, Henry starts a homily for hedonism that leaves Dorian starstruck: “I believe,” Henry coos, “that if one man were to live out his life fully and completely, were to give form to every feeling, expression to every thought…that the world would gain…a fresh impulse of joy.” Seeing a “curious new expression” come into Dorian’s face, Hallward meanwhile paints like mad, oblivious to Henry’s tirade, or the effect it has on Dorian, who drinks down Wotton’s vintage to the dregs: “He [Dorian] was dimly conscious that entirely fresh influences were at work within him. Yet they seemed to have come really from himself. The few words that Basil’s friend had said to him…had touched some secret chord…”

It is these influences that lead to the famous moment several pages later when Dorian barters his soul to stay as timeless as the picture. He gets eternal youth as the result, and starts on a trajectory toward infamy and murder. But it is the portrait’s creation that is most interesting, because it occurs at precisely the moment when Dorian’s innocence, the original source of his charm and the reason for his being there, is punctured. Basil’s painting gets is pathos from capturing the instant of his friend’s unmaking, at the hands of his mentor, elevated by his own erotic longing. “I have caught the effect I wanted,” Hallward tells them, “– the half-parted lips, and the bright look in the eyes.”

Dorian’s “most wonderful expression” is the face of Eve biting the apple. Hallward is Adam, lead astray by worshipping Eve too much. Lord Henry, of course, plays the serpent, who shakes the fruit off the tree for Eve not in an act of Miltonic revenge, but out of pure puerile recklessness: I “merely shot an arrow into the air,” Henry thinks privately, “Had it hit the mark?” It had indeed, and Henry can be sure of it once Dorian points to the young face on the canvas and cries “I would give my soul for that!”

That this moment leads Dorian to a hideous downfall should interest us much, because with his hedonistic tirade, Henry was giving the young man an aesthetic exemption from the ethical; the same pass Wilde requested from his critics during his trial, and was tartly refused. In an act of literary bravery, Wilde allowed his art to cannibalize his credibility, and he paid the price, as he knew he would. “There is no such thing as an immoral work of art,” he insisted in trial as well as his novel’s preface, but he learned to be afraid of moral art critics. They were the ones who fed excerpts from Dorian Gray’s first edition to Wilde’s prosecutors, who, with the full weight of the state behind them, hammered him to dust.

The portrait-painting scene distills the creativity that laid him on the anvil: it is art being made at a moment of moral suspension. It captures a man mentally replacing goodness with beauty. And Wilde not only allowed his art to savor such moments of suspended moral judgment, he formulated his whole theory of art on a permanent suspension of it. Another way of saying this is that Wilde was far more interested in letting mankind have its way in a drama than he was in expressing cohesive opinions — or moral systems — through it. He shared this quality with other great aphorists, and with Shakespeare. It is what John Keats called “negative capability,” which a writer has when he is “capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.” An author with negative capability can transcend his context. He can let characters have their way with the world and each other, without interceding on behalf of his own assumptions.

Though he disliked it, Wilde was not always able to avoid writing critical prose, just as he was not able to avoid going to trial. So he couched his writings in negative capability by inverting the fundamental Romantic premise: rather than seeing art as the expression of the artist’s personality a la William Wordsworth, he claimed that “art existed to conceal the artist.” Not to mention being incredibly entertaining at dinner parties, this theory allowed Wilde to free himself from the Victorian moral imperative and focus on the alternately shoddy and magnificent fireworks of the human drama, even if that meant his characters might do something the audience didn’t like. In fact he stuck to his guns even if it meant watching Henry Wotton bilk and manipulate Dorian Gray into a monster using Wilde’s very theories.

That is the last proof of his dramatic talent: it isn’t Victorian moralism which brings Dorian Gray down, but Wilde’s own counterargument to it. When Basil Hallward finally sees the hideous soul trapped in the portrait, and begs Dorian to pray for forgiveness, to have his “sins washed white as snow,” we side with Hallward, not Dorian’s petulant reply that “those words mean nothing to me now.” Dorian’s appeal to the beauty of his sins does nothing to safe him from the guilt of eventually murdering Basil, or the alienation of selfishness: he dies miserably alone, and his household feels no pity.

That Wilde allowed the novel to reach such a conclusion wasn’t pandering to his audience, it was bowing to what he knew, as a brilliant dramatist, to be a fact of human nature: that those who enshrine themselves will soon find the pedestal a prison. As the borders of Dorian’s world shrink, they are increasingly defined in lines of blood, Hallward’s among the rest. That an amoral theory of art and life could have such very real moral consequences was not a convenient conclusion for Wilde’s work to reach: it was the same one reached by his prosecutors, though they took a crude and slanderous road to get there. Wilde knew that with Dorian Gray, he’d given them the perfect ammunition; he just hoped they would be enlightened enough not to consider the lavishness of Dorian’s sin an endorsement of vice. That was his mistake — readers of tragedies have always found it hard to draw the line.

Wilde was so invested in the arts he thought he could build a defense of his honor on an aesthetic theory, but was soon reminded he was talking to a culture more like bankers then his ideal aesthete aristocrats: their fingers twitched to find the bottom line, and Dorian’s fall from grace wasn’t nearly as colorful as his flight from virtue. In the end, Wilde was sentenced to two years of hard labor, and died, discredited and unproductive, in Paris. But it was disappointment, not disgrace, that silenced him: the reality that no one could look past Dorian and Basil’s vaguely sexualized friendship, to the unity and poise with which their story was expressed, was more of a strain on him than years of pounding rocks: he came out of his sentence a wreck, and in French brothels briefly became the man London had made him out to be.

But it was his willingness to reach inconvenient conclusions (and many progressive fans find his supposed deathbed conversion to Catholicism a very inconvenient one) that set Wilde apart: capable of transcending everything to make the characters ring true, he let The Picture of Dorian Gray take on a life of its own. Preaching art for art’s sake in his lectures and at London parties, he still let Dorian reap the obscene harvest of a life lived for art’s sake alone. Wilde’s best work lives at that moment where it bucks the status quo in the name of beauty. In that sense it is a portrait of its author, and thankfully, since its only curse was to be brilliant, it could not share his fate.

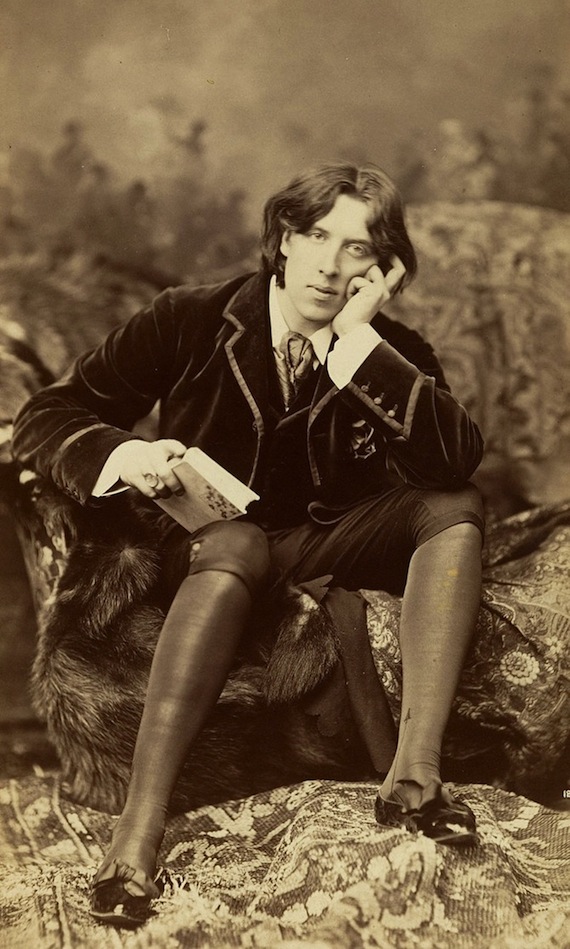

Image Credit: Wikipedia.