The first thing I did after I received a copy of New American Stories was compare its table of contents to that of its predecessor, The Anchor Book of New American Short Stories, published some 11 years earlier[i].

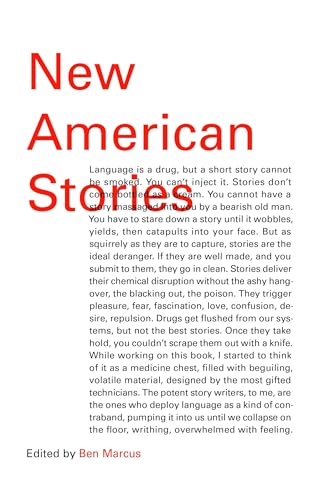

Unlike anthologies that cover a particular theme, region[ii], or narrow window of time, both New American Stories and The Anchor Book of New American Short Stories have been linked only by the fancy of their editor, Ben Marcus. Marcus is known for experimental work, but his taste ranges widely — for example, Deborah Eisenberg appears in both editions, as does George Saunders. (In fact, a quarter of the stories in New American Stories are by authors who also were published in the previous Anchor edition.[iii])

Unlike anthologies that cover a particular theme, region[ii], or narrow window of time, both New American Stories and The Anchor Book of New American Short Stories have been linked only by the fancy of their editor, Ben Marcus. Marcus is known for experimental work, but his taste ranges widely — for example, Deborah Eisenberg appears in both editions, as does George Saunders. (In fact, a quarter of the stories in New American Stories are by authors who also were published in the previous Anchor edition.[iii])

The second thing I did after I received a copy of New American Stories was read “Standard Loneliness Package” by Charles Yu. Yu is one of those guys who I’d heard of through the book review sections of newspapers, whose books I’d always meant to pick up. I follow him on Twitter. Here is a real benefit provided by anthologies like NAS: the opportunity to read work by authors who are, to varying extents, new. And so, below are my favorite three stories from the collection, all by new-to-me authors.

1.

Yu, who occupies a place somewhere between science fiction and literary fiction, does not disappoint. “Standard Loneliness Package” is about a futuristic call center where the wealthy can outsource their discomfort — physical or otherwise. It’s a clever concept, but the magic here is in Yu’s application. The story starts off with a droll description of life at the firm, a workplace filled with familiar office banter and the know-it-all colleague in the cubicle next door. But as the main character continues to toil at his job, everyone’s displaced pain takes its toll on him. He returns home at the end of each day, shaken, and cries real tears at the funeral of someone else’s grandfather. He attends another funeral and recognizes, behind the eyes of the bereaved, his coworkers. At one point, about halfway through the story, he demonstrates the anguishing monotony of grief:

I am in a hospital.

My lungs burn.

My heart aches.

I’m on a bridge.

My heart aches on a bridge.

My heart aches on a cruise ship.

My heart aches on an airplane, taking off at night.

There is a love interest, and there is real world grief. And then, just as it seems like you’ve got a handle on the story, the ground shifts again in a weird and wonderful way.

2.

And then there is “Paranoia,” a brilliant story by Saïd Sayrafiezadeh, whose memoirish essays I’d read but whose fiction was entirely unfamiliar to me. Dean, the first-person narrator of “Paranoia,” is plagued with not only with paranoia but with also its twin: confusion.

At the story’s outset, America is embarking on an unnamed war when “some line had been crossed, something said or done, something irrevocable on our said or on the enemy’s,” but the narrator is more concerned with the May heat as he rides a bus across town to visit his friend Roberto at the hospital. As he rides by “homes display[ing] the MIA and POW flags from some bygone wars, and every so often a window that said peace or no war or something to that effect,” he muses on how lucky Roberto is to have him. Dean regards Roberto as “a strange man in a strange land, hoping one day to magically transform into an American and have a real life.”

As his bus moves into “the infamous Maple Tree Heights,” fear overcomes Dean. “Every week there was a report on the news of some unfortunate event, many involving white people who had lost their way.” He gets off the bus for his transfer and thinks of taking shelter at an American-flag draped Arby’s. But then fear takes root as “three black guys about my age came out of the restaurants with their roast-beef-sandwich bags and big boots and baseball caps.” His first thought is of the violence he’s sure lurks around every corner there: “I thought about running, but running implied terror. Or capitulation.”

His fear is disrupted, somewhat, when he realizes that the group is comprised mostly of his old classmates. Dean bums a cigarette from one, which sets off what will become a series of quasi-financial transactions in the story — the lending of money, the acquisition of electronics, and the commodification of humans as soldiers and prisoners.

The story manages is funny and chilling and, somehow, a spot-on characterization of an entirely empty character.

3.

And finally, there is Mathias Svalina. Who is this guy? A poet! And it makes sense, given the lyric, absurdist group of vignettes that make up his story, “Play.” The piece itself is not a story so much as it is a rule book for a dozen absurdist children’s games, with narratives folded in. I read most of “Play” aloud to my husband, and it will be difficult not to quote each section, in its entirety, here.

“Drop the Handkerchief” imagines a complicated game that is part duck-duck-goose, part public shaming. A child is born It, and then chooses another child to join him. The other five children stand in a circle and “hold hands & refuse to allow either the It-child or the chosen child to stop running. These two continue running for the rest of their lives.”

There is also a child born inside the circle. He, too, has a handkerchief, left for him by his estranged father, who “drives a bright blue car & can be seen working at the candle factory five nights a week.”

In “Pop Goes the Weasel,” designed for four children “and an audience of voters,” a child is designated It.

The It child walks into a crowd of thousands, shaking hands with all the men & kissing the cheeks of all the women & rubbing perfumed oils on the foreheads of all the babies. He must appear on TV & pretend like there is no camera in the room.

Later, when the It child is assassinated, the other children write books about him or her.

The games are united by motifs of masculinity and competition, with a decided emphasis on losing. They also often feature children engaging in pretend commerce, as with “Hide-&-Go-Seek” and “Everything Costs $20.” Of course, much of child’s play is actually about engaging in pretend commerce. This is another way Svalina’s piece succeeds — the story, in its absurdity, still manages to tread in the familiar.

Marcus recently said, in an interview with Flavorwire, that he does not want New American Stories to feel like a declaration of what is worthwhile as much as he wants it be experienced like a literary mixtape. But the book is, in fact, a reflection of what many American writers are thinking about today — the limitations of late capitalism, the rush to quantify and app=ify every human need, the constant thrum of American interventions. Like the previous edition, here is a snapshot of our time, grim and funny and unreal.

[i]. The new edition is published by Vintage; both Vintage and Anchor are imprints of Penguin Random House.

[ii]. Even “American” is very loosely defined. Zadie Smith, for instance, is English, although she has made New York City her part-time home.

[iii]. Lydia Davis, Anthony Doerr, Deborah Eisenberg, Mary Gaitskill, Sam Lipsyte, George Saunders, Christine Schutt, Wells Tower.