Tom Nissley’s column A Reader’s Book of Days is adapted from his book of the same name.

Did Dickens invent Christmas? It’s sometimes said he did, recreating the holiday as we know it out of the neglect that had been imposed on it by Puritanism, Utilitarianism, and the Scrooge-like forces of the Industrial Revolution. But Dickens himself would hardly have said he invented the traditions he celebrated: the mission of his Ghost of Christmas Present, after all, is to show the spirit and customs of the holiday are authentic and alive among the people, not just humbug. But A Christmas Carol did appear alongside the arrival in Victorian England of some of the modern traditions of the holiday. It was published in 1843, the same year the first commercial Christmas cards were printed in England, and two years after Prince Albert brought the German custom of the Christmas tree with him to England after his marriage to Queen Victoria.

Did Dickens invent Christmas? It’s sometimes said he did, recreating the holiday as we know it out of the neglect that had been imposed on it by Puritanism, Utilitarianism, and the Scrooge-like forces of the Industrial Revolution. But Dickens himself would hardly have said he invented the traditions he celebrated: the mission of his Ghost of Christmas Present, after all, is to show the spirit and customs of the holiday are authentic and alive among the people, not just humbug. But A Christmas Carol did appear alongside the arrival in Victorian England of some of the modern traditions of the holiday. It was published in 1843, the same year the first commercial Christmas cards were printed in England, and two years after Prince Albert brought the German custom of the Christmas tree with him to England after his marriage to Queen Victoria.

Christmas was undoubtedly Dickens’s favorite holiday, and he made it a tradition of his own. A Christmas Carol was the first of his five almost-annual Christmas books (he regretted skipping a year in 1847 while working on Dombey and Son; he was “very loath to lose the money,” he said. “And still more so to leave any gap at Christmas firesides which I ought to fill”), and then for eighteen more years he published Christmas editions of his magazines Household Words and All the Year Round. And the popular and exhausting activity that nearly took over the last decades of his career, his public reading of his own works, began with his Christmas stories. For years they remained his favorite texts to perform, whether it was December or not.

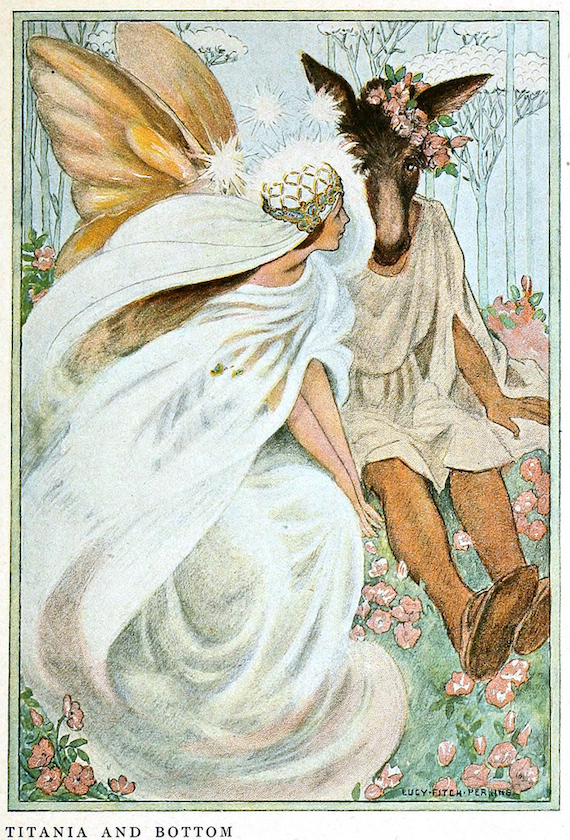

One of the Christmas traditions Dickens most wanted to celebrate is one mostly forgotten now: storytelling. The early Christmas numbers of Household Words were imagined as stories told around the fireplace, often ghost stories like A Christmas Carol. It’s an easily forgotten detail that the classic American ghost tale, Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw, is also told around the Christmas hearth. James begins his tale with the mention of a story told among friends “round the fire,” about which we learn little except that it was “gruesome, as, on Christmas Eve in an old house, a strange tale should essentially be,” and that it involved a child. Three nights later that story inspires another, even stranger and more unsettling and involving not one child but two, a ratcheting of dread that gave James the title for his tale.

Telling ghost stories around the hearth might have declined since Dickens’s and James’s times, but it’s striking how important the voice of the storyteller remains in more recent Christmas traditions: Dylan Thomas, nostalgic for the winters of his childhood in “A Child’s Christmas in Wales”; Jean Shepherd, nostalgic for the Red Ryder air rifles of his own childhood in In God We Trust, All Others Pay Cash, later adapted, with Shepherd’s own narration, into the cable TV staple A Christmas Story; and David Sedaris, nostalgic for absolutely nothing from his years as an underpaid elf in the “SantaLand Diaries,” the NPR monologue that launched his storytelling career.

Gather round the fire with these December tales:

Rock Crystal by Adalbert Stifter (1845)

Rock Crystal by Adalbert Stifter (1845)

In a Christmas tale of sparkling simplicity, a small brother and sister, heading home from grandmother’s house on Christmas Eve across a mountain pass, find their familiar path made strange and spend a wakeful night in an ice cave on a glacier as the Northern Lights–which the girl takes as a visit from the Holy Child–flood the dark skies above them.

The Chemical History of a Candle by Michael Faraday (1861)

Dickens was not the only Victorian with a taste for public speaking: Faraday created the still-ongoing series of Christmastime scientific lectures for young people at the Royal Institution, the best known of which remains his own, a classic of scientific explanation for readers of any age.

Little Women by Louisa May Alcott (1868)

Little Women by Louisa May Alcott (1868)

If you were one of the March girls, you’d read the copies of The Pilgrim’s Progress you found under your pillow on Christmas morning, but we’ll excuse you if you prefer to read about the Marches themselves instead.

Appointment in Samarra by John O’Hara (1934)

Julian English’s three-day spiral to a lonely end, burning every bridge he can in Gibbsville, Pennsylvania, from the day before Christmas to the day after, is inexplicable, inevitable, and compelling, the inexplicability of his self-destruction only adding to his isolation.

“The Birds” by Daphne du Maurier (1952)

Hitchcock transplanted the unsettling idea of mass avian malevolence in du Maurier’s story from the blustery December coast of England to the Technicolor brightness of California, but the original, told with the terse modesty of postwar austerity, still carries a greater horror.

The Catcher in the Rye by J. D. Salinger (1951)

The Catcher in the Rye by J. D. Salinger (1951)

Holden’s not supposed to be back from Pencey Prep for Christmas vacation until Wednesday, but since he’s been kicked out anyway, he figures he might as well head to the city early and take it easy in some inexpensive hotel before going home all rested up and feeling swell.

Instead of a Letter by Diana Athill (1963)

The “twenty years of unhappiness” recounted in Athill’s memoir, after her fiancé wrote to say he was marrying someone else just before being killed in the war, ended on her forty-first birthday with the news she had won the Observer‘s Christmas story competition (the same prize that launched Muriel Spark’s career seven years before).

Tape for the Turn of the Year by A. R. Ammons (1965)

Tape for the Turn of the Year by A. R. Ammons (1965)

The long poem was a form made for Ammons, with its space to wander around, contradict himself, and turn equally to matters quotidian and cosmic, as he does in this lovely experiment that, in a sort of serious joke on Kerouac, he composed on a single piece of adding machine tape from December 1963 to early January 1964.

Chilly Scenes of Winter by Ann Beattie (1976)

Want to extend The Catcher in the Rye’s feeling of unrequited holiday ennui well into your twenties? Spend the days before New Year’s with Charles, impatient, blunt, and love-struck over a married woman whom he kept giving Salinger books until she couldn’t bear it anymore.

The Ghost Writer by Philip Roth (1979)

The Ghost Writer by Philip Roth (1979)

The brash and eventful fictional life of Nathan Zuckerman, which Roth extended in another eight books, starts quietly in this short novel (one of Roth’s best), with his abashed arrival on a December afternoon at the country retreat of his idol, the reclusive novelist E. I. Lonoff.

The Orchid Thief by Susan Orlean (1998)

Head south with the snowbirds to the humid swamps of Florida as Orlean investigates the December theft of over two hundred orchids from state swampland and becomes fascinated by its strangely charismatic primary perpetrator, John Laroche.

Stalingrad by Antony Beevor (1999)

Stalingrad by Antony Beevor (1999)

Or perhaps your December isn’t cold enough. Beevor’s authoritative account of the siege of Stalingrad, the wintry graveyard of Hitler’s plans to conquer Russia, captures the nearly incomprehensible human drama that changed the course of the war at a cost of a million lives.

The Year of Magical Thinking by Joan Didion (2005)

Didion’s year of grief, recorded in this clear-eyed memoir, began with her husband’s sudden death on December 30, 2003, and ended on the last day of 2004, the first day, as she realized to her sorrow, that he hadn’t seen the year before.

Last Day at the Lobster by Stewart O’Nan (2007)

Last Day at the Lobster by Stewart O’Nan (2007)

Manny DeLeon will be all right—he has a transfer to a nearby Olive Garden set up—but in his last shift as manager of a Connecticut Red Lobster, shutting down for good with a blizzard on the way, he becomes a sort of saint of the corporate service economy in O’Nan’s modest marvel of a novel.

December by Alexander Kluge and Gerhard Richter (2012)

Two German artists reinvent the calendar book, with Richter’s photographs of snowy, implacable winter and Kluge’s enigmatic anecdotes from Decembers past, drawing from 21,999 b.c. to 2009 a.d. but circling back obsessively to the two empires, Nazi and Soviet, that met at Stalingrad.