Learn about our newest title, The Pioneer Detectives

The Millions turns 10 years old this year, and to celebrate, we’re trying something new. The Millions Originals will give our talented writers a platform to publish as ebooks longer, magazine-quality pieces that will explore a variety of unusual and interesting topics. They cost just $1.99 and provide a jolt of entertainment that we hope will be worth much more than the price. Our ebooks will generally run about 15,000 words (a good deal longer than most magazine articles, but not nearly as long as a book). So please, hop on over here to learn a bit more about our first title and to buy it from the ebookstore of your choice. Or, read on for an excerpt, if you still need convincing.

The Millions turns 10 years old this year, and to celebrate, we’re trying something new. The Millions Originals will give our talented writers a platform to publish as ebooks longer, magazine-quality pieces that will explore a variety of unusual and interesting topics. They cost just $1.99 and provide a jolt of entertainment that we hope will be worth much more than the price. Our ebooks will generally run about 15,000 words (a good deal longer than most magazine articles, but not nearly as long as a book). So please, hop on over here to learn a bit more about our first title and to buy it from the ebookstore of your choice. Or, read on for an excerpt, if you still need convincing.

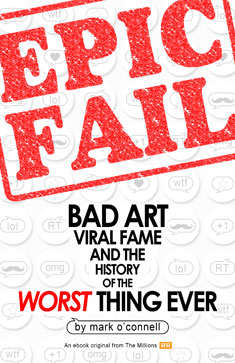

To kick off our new series, Dublin-based staff writer Mark O’Connell has penned an exploration of the Internet-era obsession with terrible art – bad YouTube pop songs, Tommy Wiseau’s The Room, and that endless stream of “Worst Things Ever” that invades your inboxes, newsfeeds, and Twitter streams. What, exactly, draws us to these futile attempts at making songs, movies, and art? What are the essential ingredients that render a ridiculous failure sublime? More importantly, what does our seemingly insatiable appetite say about our aesthetic impulses? In setting out to answer these questions, O’Connell uncovers the historical context for our affinity for terrible art, tracing it back to Shakespeare and discovering the early 20th-century novelist who was dinner-party fodder for C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien. Read on for the first chapter of The Millions‘ first ebook original, Epic Fail: Bad Art, Viral Fame, and the History of the Worst Thing Ever. – C. Max Magee, editor, The Millions

* * *

1. Behold the Monkey

In the Sanctuary of Mercy church in the town of Borja, in northern Spain, there used to be a fresco by the 19th-century painter Elías García Martínez. It was a fairly standard Ecce Homo scene, portraying the scourged Christ—the crown of thorns, the expression of serene forgiveness—in the moments before crucifixion. No one much cared about this fresco. It was the unremarkable work of a minor painter, of little or no interest to art historians, and the priests and parishioners of the Sanctuary of Mercy clearly didn’t hold it in especially high regard either. Until recently, Martínez’s fresco was in a state of severe decline, with most of the paint having rubbed off around the middle of Christ’s torso and some pretty serious chipping and flaking going on toward the right-hand side of His face. Because no one else had bothered to do anything about it, and because the church seemed uninterested in commissioning a professional restoration, an 81-year-old parishioner named Cecilia Giménez decided to take matters into her own hands. She had lived in Borja and worshiped at Sanctuary of Mercy all her life; even if the fresco was not a parish priority, she saw artistic and devotional value in it and was upset to see it fall into disrepair. She did her best with her limited talents, but the restoration attempt was not successful, and the fresco looked considerably worse by the time she was through. The attempt was so badly botched, in fact, that she wound up becoming internationally famous because of it. For a while there, Cecilia Giménez was probably the most talked-about artist in the world.

Chances are you’ve seen the result of her work, in which Martínez’s Christ is transfigured into what looks like a beady-eyed baboon wearing an ushanka. It very quickly became an iconic image; the Spanish took to calling it Ecce Mono (Behold the Monkey), while in the English-speaking world it became known simply as “the Jesus fresco.” For much of the late summer and early autumn of 2012, you couldn’t go online or open a newspaper without seeing it. People were obsessed not just with the aesthetic monstrosity of the restoration itself but with the idea of the devout and well-intentioned octogenarian who had created it. Twitter timelines filled with jokes about Giménez and links to articles about her, and tribute Tumblrs featured smudgily simian faces gimmicked onto the Mona Lisa, The Last Supper, Van Gogh’s self-portraits, Warhol’s Marilyn, Michelangelo’s David, Munch’s The Scream. The Financial Times, Der Spiegel, The New York Times, and Libération all covered the story of the restoration. The chief art critic for The New Statesman skittishly considered its supreme incompetence on Sky News. And here was the poor woman herself, grilled by television journalists, poignantly insisting that she had the full permission of the parish priest and that, anyway, she hadn’t finished the retouch yet; she had been called away mid-job to go on a trip with her son. (“When I got back, the whole village was there, and I couldn’t defend myself! I said, ‘Let me finish it,’ and they said not to touch it!”). More than 23,000 people signed an online petition to have the piece preserved in its current, profanely post-Giménez form. In a more or less textbook illustration of postmodern irony, the Church of the Face-palm Fresco became a site of tourist pilgrimage, a sacred location beyond the event horizon where ridicule becomes veneration. “The truth,” as one local small-business owner put it in a television-news interview, “is that we should be thanking her because of how much it has helped catering trade in the town. We were having economic problems, and now, thanks to this woman, we are recovering.”

Anyone who had read Don DeLillo’s novel White Noise would have found it difficult not to think of the famous scene in which Jack Gladney (professor of Hitler Studies) and his colleague Murray Siskind drive out into the New England countryside to visit a tourist attraction known as “the Most Photographed Barn in America.” They stand back from the crowd of tourists, observing them as they take photographs of a building that is noteworthy solely for the frequency with which people like themselves take photographs of it. In the epigrammatically deadpan idiom of DeLillo’s characters, Murray refers to the scene as “a religious experience in a way, like all tourism.” They are, as he puts it, “taking pictures of taking pictures.”

What was being enacted here, in the little town of Borja, was a kind of exponentially ironic pilgrimage. The object of fetishization was not so much the icon as the very act of fetishization itself—of participating in, and contributing to, the fame of the thing being venerated. More troubling, though, was the fact that this involuted self-regard was also characteristic of the precise way in which Cecilia Giménez herself had become famous. The consideration of her fame, in other words, was itself a major element of that fame. The woman herself became caught up in the seething vortex of our cultural self-fascination.

* * *

The Face-palm Fresco Affair is a definitive example of our obsession with a particular kind of bad art. Its watchword is “Epic Fail”—the collective cry of elated online schadenfreude that greets each new disastrous attempt to create art or entertainment. The success, through captivating dreadfulness, of R. Kelly’s R&B opera buffa Trapped in the Closet. The brief but intense fame of the impressively atrocious American Idol contestant William Hung. The meme mother lode that was Insane Clown Posse’s attempt to illuminate the wonder of everyday “Miracles” (“Fuckin’ magnets: how do they work?”). The Irish mother-daughter-and-son country trio Crystal Swing, whose viral success with their transcendently lame and somehow insidiously creepy video for “He Drinks Tequila” saw them appear on The Ellen DeGeneres Show without any apparent awareness that they were an object of fun. Every day brings some new fantastic artistic outrage, some new Greatest Worst Thing Ever. There is now an entire echelon of viral celebrity populated by people—your Crystal Swings, your Giménezes—who have become known for their resounding failures.

I suspect that had the Spanish fresco simply been the anonymous work of an unknown guerrilla retoucher—if there wasn’t a body to be seen to undergo the indignity of the slapstick—the story would not have been nearly as compelling to nearly as many people. The personal element is crucial, and this is what accounts for the paradoxically humanistic and cruel constitution of the Epic Fail. It is predicated not just on the appreciation of the failed artwork but also on the aesthetic fetish for a particular misalignment of confidence and competence. We insist, in our judgments, on a sort of cultural habeas corpus. We don’t just want to look at the horribly disfigured Jesus fresco or listen to the horribly misfired effort at a pop song; we want to look at the person who thought they were talented enough to pull these things off in the first place. And I think part of our perverse attraction to these people and to the bad art they make is a particular sort of authenticity. Vigilant self-consciousness is both a primary component and a primary product of our online culture; an entire generation of Westerners (i.e., mine) has become preoccupied with the curation of permanent exhibitions of the self. We hate ourselves for the inauthenticity of these exhibitions, even if we wouldn’t have it any other way. And so the Epic Fail is, among other things, a paradoxical ritual whereby a pure strain of un-self-consciousness is globally venerated and ridiculed.

To watch an interview with Cecilia Giménez is to glimpse the strange and flamboyant cruelty of this phenomenon. The scale, the intensity, and the bewildering modernity of the attention that has been imposed upon her is something by which she is very clearly mortified—an essentially Catholic term, this. Soon after the restoration attempt went viral, she retreated behind closed doors and took to her bed, in the grip of a sustained anxiety attack. According to her family, they were having trouble getting her to eat anything. Perhaps, then, it’s worth thinking about what is truly emblematic of our contemporary culture here—and where the real Epic Fail actually is. Is it the smudged, monkey-faced Jesus and the exultantly amused response it provoked, or is it the debilitating case of viral celebrity now afflicting a frail old lady who just wanted to do some small good deed for her church?

Special thanks to our pals at Byliner who helped us turn our idea into an ebook.

Click here to buy the book from the ebookstore of your choice for $1.99.