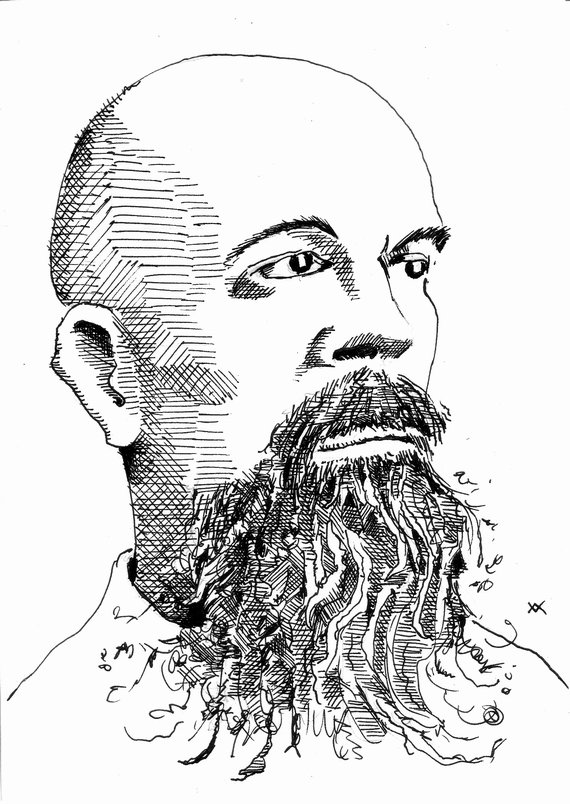

Neal Stephenson by Bill Morris. email Bill.

In his book, Extra Lives: Why Video Games Matter, Tom Bissell writes, “More than any other form of entertainment, video games tend to divide rooms into Us and Them. We are, in effect, admitting that we like to spend our time shooting monsters, and They are, not unreasonably, failing to find the value in that.” Bissell is an avid gamer whose collection of essays on the industry attempts to illuminate — and partially, he admits, to justify — the vast amounts of time he and his peers spend shooting monsters and saving the pixelated world.

In his book, Extra Lives: Why Video Games Matter, Tom Bissell writes, “More than any other form of entertainment, video games tend to divide rooms into Us and Them. We are, in effect, admitting that we like to spend our time shooting monsters, and They are, not unreasonably, failing to find the value in that.” Bissell is an avid gamer whose collection of essays on the industry attempts to illuminate — and partially, he admits, to justify — the vast amounts of time he and his peers spend shooting monsters and saving the pixelated world.

Bissell wrote an engaging, beginner-friendly book that I turned to with unanswered questions — questions that had been raised, and then ignored, by Neal Stephenson. Stephenson’s latest novel, Reamde, centers around T’Rain, a massively multi-player online role-playing game (MMORPG) that has (fictionally) surpassed World of Warcraft in innovation and popularity.

MMORPGs differ from other video games in that thousands of players all exist in the same virtual world. If you’re playing Grand Theft Auto, you’re up against the game as it was designed. But in a MMORPG like T’Rain, the details of the world you’re playing in are being determined by the other players online. It’s easy to see why this kind of game is even more addicting than its more confined peers. Grand Theft Auto lies dormant without you when turned off, but T’Rain is always changing. Richard Forthrast, the founder of T’Rain, describes it thus:

MMORPGs differ from other video games in that thousands of players all exist in the same virtual world. If you’re playing Grand Theft Auto, you’re up against the game as it was designed. But in a MMORPG like T’Rain, the details of the world you’re playing in are being determined by the other players online. It’s easy to see why this kind of game is even more addicting than its more confined peers. Grand Theft Auto lies dormant without you when turned off, but T’Rain is always changing. Richard Forthrast, the founder of T’Rain, describes it thus:

This was part of Corporation 9592’s strategy; they had hired psychologists, invested millions in a project to sabotage movies, yes, the entire medium of cinema—to get their customers/players/addicts into a state of mind where they simply could not focus on a two-hour-long chunk of filmed entertainment without alarm bells going off in their medullas telling them that they needed to log on to T’Rain and see what they were missing.

The main objective of T’Rain players is wealth, both virtual and actual. T’Rain characters can earn money in the game’s feudal system or steal it from those they vanquish. It’s designed to appeal both to casual players who want to log on and battle something periodically and to Chinese teenagers who make a living from playing it incessantly.

Forthrast was a big gamer before he founded T’Rain, and from the beginning the game was designed with massive worldwide popularity in mind. He hired a geology expert to create the planet T’Rain’s geography and climate. He hired two science-fiction writers—one a Cantabridgian Tolkien-like figure and the other a prolific producer of pulp—to write the history of T’Rain—it’s species, nations, ancient feuds, and continuing mythology. They spent years creating T’Rain, so that it was a complete universe and set of cultures before they invited the players in. Fast forward a few years, T’Rain is ubiquitous and Richard Forthrast is a multi-millionaire.

I liked Reamde right away. It begins at the Forthrast family reunion in Iowa, where we learn Richard’s backstory, how he came up with the idea for T’Rain and assembled its hodge-podge team of designers and writers. He talks about MMORPGs, their particularly enticing qualities and how the game company continues to shape the world the players play in without exerting obvious influence. Bissell writes that every video game has a guiding story. “PLUMBER’S GIRLFRIEND CAPTURED BY APE!”, as he says, was the original game story, and they have evolved from that into worlds of moral quandary.

In T’Rain, characters are either good or evil. T’Rains writers created a history of wars between the two, which new players take up as they join the game. However, as the players become more personally invested in the game’s world, the battle lines started to shift. T’Rain’s two writers — the Tolkien guy and the pulp guy — are public rivals, and the game’s players start taking sides, in what Richard calls the War of Realignmnet (Wor).

“So the Wor is our customers calling bullshit on our ‘Good/Evil’ branding strategy,” Richard says to one of his writers, who replies, “Not so much that as finding something that feels more real to them, more visceral.”

T’Rain’s players are so plugged in that they’re taking over the story. Meanwhile, a Chinese hacker creates a T’Rain virus, Reamde, that encrypts the infected computer’s files and holds the encryption key ransom. The ransom, of course, is to be paid within T’Rain. As Stephenson describes it, the world of T’Rain and the real world stop feeling distinct. T’Rain isn’t so much a hobby to its players, as a second way to live out their life. That distinction between the Us and Them that Bissell describes, and what makes the Us so crazy about gaming, is one I thought Stephenson was going to keep exploring.

And then, how do I say this, enter a pack of jihadists. Richard’s niece and her boyfriend, helping to track down the Chinese hacker, literally stumble upon an Islamic terrorist’s bomb factory. For the rest of the book, there are many many gunfights.

Stephenson, known for his supernatural themes, says he wanted to try something different by writing a thriller. This he did, and the final two-thirds of the book is a lively thriller, with Richard’s niece assigned the Kim Bauer role of the constantly handcuffed and espionage agents from Russia, England, and the U.S. all getting involved as the action hops from continent to continent. The problem is, Stephenson showed his hand too much at the beginning. He teased me with a thriller that took place within T’Rain, among its players and runners, visited upon by the limitations and consequences of two simultaneous worlds—real and virtual. I so wanted to read that book. But it was pushed to the background to make way for a shoot-em-up.

This is the first Stephenson I’ve read, and I now gather it was a bad place to start. From Reamde, I know him to be a thoughtful, meticulous, and very funny writer (of an MI6 agent going dark in British Columbia, “How could your cover be blown in Canada? Why even bother going dark there? How could you tell?”), but his talents were misplaced here. He continued to bring T’Rain into the plot. The characters use it to communicate with each other, and the Reamde virus scenario still plays out, although with nothing like the significance the title suggests. The T’Rain novel and the thriller feel like two separate books, the lesser of which gets more attention, sending me running for Tom Bissell to satisfy my new-found interest in gaming. If Stephenson ever decides to finish the T’Rain novel, I’m interested.