1. The non-fictional part

My father returned to British Columbia last week. He’d been in New York City for three years, the only three years of my adult life when I’d had a blood relative within three thousand miles; there’s absolutely no reason, in other words, why I shouldn’t be accustomed to living on the other side of a continent and across an international border from my family by now, but it’s hard to describe the wistfulness that overcame me when he left. Words scrawled in a notebook on the subway last week: All my family’s by the opposite ocean tonight. I love New York so deeply, but I am so far away.

Immigration has been on my mind lately. A grandmother’s family is of aristocratic lineage, which means absolutely nothing except that it makes genealogical research really easy; our ancestors can be traced back to the year 800, a Viking king, but that was four countries ago now. From Denmark to France, a sea crossing to England at the time of the conquest, several centuries of lives and deaths and high-stakes political maneuverings before a magnificently-named great-grandfather set out for the New World: Newell St. Andrew St. John, eighteen years old, the recipient of a beautiful classical education, known all his life for his warmth and kindness, boards a ship out of England and boldly notes his occupation as Farmer on the manifest.

It’s less than certain that he’d ever wielded a shovel before he wrote that word. The prairie farm that followed was of course a disaster. But what spirit, what evidence of the will for self-creation, of the possibilities the new continent offered! It was possible, at least on paper, to come here and be an entirely new person. I wish I could have known him. I imagine him on the Canadian prairies, gazing out at the bafflingly endless land, thinking Now what?

There were a number of slow journeys over oceans in my great-grandparents’ generation, but their children had the sense to stay put. My grandparents’ lives were played out in Canada (my mother’s side) and the United States (my father’s); Victoria and the Canadian prairies, small California towns. But my father moved from California to Canada as a young man and has switched countries three or four times since. I moved from Toronto to New York City, back up to Montreal, back to New York. I acquired a second passport.

It occurred to me, arriving in New York City by train for the second time in a year, that it would be perfectly possible to go on like this forever. City to city, country to country, endless mundane interchangeable jobs, a permanently unsettled life. I got a novel out of this realization, but the thought gave me a chill.

2. The reading list.

(I’ve left out the obvious ones, because you’ve probably all heard of Brooklyn and The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by now.)

Migration in its various forms is at the heart of a great many of my favorite plots in fiction. But beyond that it seems to me that migration, as an idea of motion, is inextricable from good fiction. Your characters must change—they must move, psychically at least, from point A to point B—and the plot must move forward.

Drowning in Darkness, by Peter Oliva: I found this slim paperback in my grandparents’ living room when I was fourteen or so, and have carried it with me ever since. An exquisitely-written novel that takes place mostly in a grim little mining town in Canada’s Crowsnest Pass. A coalminer named Pep Rogolino imported a bride, Sera, from southern Italy; she came dreaming of a spectacular new life, sank under the weight of the life she found in Canada, and eventually disappeared. Did she flee the town? Did she walk into the coalmine, where deadly gasses move silently through the dark? The narrative cuts back and forth between Pep and Sera’s lives, together and apart, and a single night in the coal mine: a young miner, trapped by an explosion, tells stories to someone who may or may not be there with him in the absolute darkness while he waits to Pep to arrive with the morning shift.

The Mistress of Nothing, by Kate Pullinger: Sally Naldrett is a maid at the service of Lady Duff Gordon, an effervescent (and consumptive) member of Victorian-era British high society. When Lady Duff Gordon’s worsening health forces her to flee damp England for hotter, drier climes, Sally travels with her, into a new life in Egypt that she never could have imagined. I rarely read historical fiction, but found this book absolutely captivating.

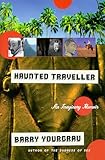

Haunted Traveller by Barry Yourgrau: Haunted Traveller is billed as a fictional memoir. It’s made up of episodic little sections, connected loosely or not at all, concerning travels in countries that might almost be real. The elements are fantastical, but the underlying theme—the disconnection and alienation of solo travel—rings absolutely true.

The Brief History of the Dead by Kevin Brockmeier: Death is another country, or in Brockmeier’s novel, another city. The City is populated by the recently deceased; its origins and exact nature are unclear, but it’s clear to the inhabitants that it’s something akin to a way station. The last migration you take is to The City, where you remain for weeks or years or decades, until the death of the last person on earth who remembers you. But the living world has become increasingly chaotic, with warfare and plagues spreading over the continents; new arrivals in the city bring ever more desperate accounts of a new and unstoppable virus. As the human race nears extinction, The City begins to empty out. Back on earth, a lone researcher named Laura Byrd is trapped by bad weather in an Antarctic research station. As her supplies dwindle and she struggles for survival, the citizens of the shrinking City realize that Laura Byrd, the one person they all seem to have in common, is very likely the last person alive on earth.