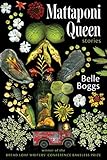

In his preface to Mattaponi Queen, the recipient of the 2010 Bakeless Fiction Prize awarded by the Breadloaf Writers Conference, Percival Everrett states, “It is always good to hear new voices, but the newness of a voice alone carries no literary value.” This is a telling statement in regards to Belle Boggs, for though the stories contained in Mattaponi Queen comprise Boggs’ debut, they give the impression of a writer who has been lingering in our midst for many years.

In his preface to Mattaponi Queen, the recipient of the 2010 Bakeless Fiction Prize awarded by the Breadloaf Writers Conference, Percival Everrett states, “It is always good to hear new voices, but the newness of a voice alone carries no literary value.” This is a telling statement in regards to Belle Boggs, for though the stories contained in Mattaponi Queen comprise Boggs’ debut, they give the impression of a writer who has been lingering in our midst for many years.

Often reviews will cite passages, lines and turns that encompass the greater themes of a work as a whole, Boggs’ writing is not the type that necessarily lends itself to quotation. She is not a stylist whose isolated sentences will jump off of the page, but when taken as a whole the reader learns to appreciate them in the same manner one might marvel at the individual thread so as to fully understand the tapestry it helps to create, and her writing possesses a gravitas and earnestness that belies her youth.

Mattaponi Queen takes as its subject matter the plethora of characters who inhabit the rural backwoods of King and Queen County, Virginia. Because of this, Boggs has and will invariably draw comparisons to Susan Straight and Victoria Patterson, other notable contemporary writers whose debut collections revolved around the notion of place and the “identity” afforded by it, but unlike her California compatriots, Boggs’ work is steeped in the idea and myth of the American South, and despite having spent time in Brooklyn and Irvine—where she earned her MFA—Boggs’s work is Faulknerian in its consistency. Still, whereas Faulkner’s verbosity proclaimed a writer tasked with penning into being a people displaced by the loss of a confederacy that never truly was, Boggs’ work quietly reminds us that they are still there, and her main skill is in showing us that although her residents are, by dint of their addresses, “Southern” they are more so citizens of a world that, like a town along Route 66, has been doomed by the approach of an interstate being constructed mere miles away. Far from being harbingers of good fortune, in Boggs’ world time and progress are the enemy, bringing with them more issues, problems and fears that will hang in dubiously in the air like the dense humidity commonly smothering the Virginia landscape.

Mattaponi Queen takes as its subject matter the plethora of characters who inhabit the rural backwoods of King and Queen County, Virginia. Because of this, Boggs has and will invariably draw comparisons to Susan Straight and Victoria Patterson, other notable contemporary writers whose debut collections revolved around the notion of place and the “identity” afforded by it, but unlike her California compatriots, Boggs’ work is steeped in the idea and myth of the American South, and despite having spent time in Brooklyn and Irvine—where she earned her MFA—Boggs’s work is Faulknerian in its consistency. Still, whereas Faulkner’s verbosity proclaimed a writer tasked with penning into being a people displaced by the loss of a confederacy that never truly was, Boggs’ work quietly reminds us that they are still there, and her main skill is in showing us that although her residents are, by dint of their addresses, “Southern” they are more so citizens of a world that, like a town along Route 66, has been doomed by the approach of an interstate being constructed mere miles away. Far from being harbingers of good fortune, in Boggs’ world time and progress are the enemy, bringing with them more issues, problems and fears that will hang in dubiously in the air like the dense humidity commonly smothering the Virginia landscape.

Still, while Boggs’ characters are rural, they are anything but folksy. They are cosmopolitan in their own way—people with dreams and ideas of betterment. People who, like George in Boggs’ penultimate story “Shelter,” lie in bed and imagine “Brick with dark shutters, a little green yard in front. Trees lining the street. Kids riding bicycles…” yet full-well knowing that this cartoon-like fantasy of suburbia is a place beyond them. It is something not allowed, for to live in the literal and figurative space of King and Queen County is to reside deep inside the many sinkholes that pock the country. The surface is a faraway place protected from their advances by steep and slick walls of dirt and limestone, and even should one be able to taste some semblance of life on the surface George understands that betterment often comes from trading in a view of a cornfield for one with a bus shelter. To survive in Boggs’ world one must learn quickly how to differentiate small victories from hollow ones.

The language of Mattaponi Queen is simple, but precise and skilled, as Boggs has a knack for capturing both the comedy and absurdity in all levels of human relationships that, in the hands of a lesser writer, would smack heavily of the melodramatic and the clichéd fables of the downtrodden, but the failures of her characters are active ones. They do not curse fate nor do they resign themselves to it, but gaze upon it with the unique perspective that allows a character who has recently attempted suicide to write to a friend that he will be returning home from the hospital soon. The assumption being that he is recovering, until Boggs concludes her paragraph with the darkly funny “as soon as his mom’s insurance money ran out.”

In Mattaponi Queen this gallows humor proves necessary, and often one is unclear whether the light at the end of the tunnel signals the brilliance of the sun or a rapidly approaching train. But her characters are more than snarky derelicts. They are questioning beings, ones often searching for meaning to an isolated existence or to recapture a moment, now gone forever, in which they believed themselves to be truly happy even as Boggs’ narration reveals to the reader how it is all self-delusion, an illusion born of nostalgia for anything but the present moment. They bend and twist and contort, but even if small fissures develop in the process, they remain unbreakable.

If one attempted to define the uniting theme behind Mattaponi Queen besides its geography, they would be left with a discourse on love in all its various unrequited and confused forms. For Ronnie, the pregnant wife of a maimed veteran, it is “Something you thought you should have until it was right there in front of you and you realized you were committed to it whole.” For Melinda it is the silent understanding that in accepting her husband’s sex change, she will forever destroy her relationship with her daughter. But through all of this Boggs never offers anything resembling answers, let alone truisms, for unlike her characters she knows the questions she poses to be unanswerable and their the discovery of anything will bring with it not knowledge and wisdom but more confusion and more catalysts for further confusion.

Of all of Boggs’ characters, though, it is Loretta, the black middle-aged caretaker of an elderly, somewhat aristocratic white widow Cutie (who will conjure in many Julian’s mother from Flannery O’Connor’s classic “Everything that Rises Must Converge”), who comes to dominate the book both through her reappearances and her stability in navigating multiple worlds, multiple relationships and multiple storylines. Thus it is not surprising that if anyone can escape King and Queen County, a place that “used to be more interesting than it is now,” it should be her, even if that escape is less physical than fantastical. But contained within Loretta is Boggs’ message en masse—hope and an understanding that it is precisely because of its stasis that King and Queen county and its people are interesting, and for Boggs an otherwise overlooked milieu in a forgotten part of a state that strives for sophistication even as it clings to its Confederate heart with compassion and tenderness needs a voice worthy of their station and confusion and resilience. And, as Everett overtly implied by his selection of Mattaponi Queen as the 2010 Bakeless Prize Winner, Boggs is this a new voice with a strong and profound value.