In certain bus stops around Paris, there’s an ad up for for Sex and the City 2: a glittery stiletto heel crushes a soccer ball, while the caption reads: “In theaters during the World Cup.”

With slight modification it could have been the poster for the fourth biannual Shakespeare and Company literary festival, which also took place in Paris this weekend during the World Cup, except instead of watching the game we were listening to Martin Amis declare himself a “millenarian feminist.” Always on the periphery of the festival, the Cup provided the ambient background (cars driving by on the quai, honking and flag-waving; crowds cheering in front of Notre Dame and in nearby bars) as well as a ready metaphor for many of the panels. The theme of the festival was “Storytelling and Politics,” and over three days, 6,000 people gathered in a tent in a small park across the river from Notre Dame to hear writers like Will Self, Martin Amis, Fatima Bhutto, Ian Jack, Breyten Breytenbach, Philip Pullman, Hanif Kureishi, Nam Le, Petina Gappah, and Jeanette Winterson talk through the relationship between the storyteller and his political context. But the World Cup was on everyone’s mind; in nearly every session I attended, someone tossed off a reference to it…

National literatures are like national teams

…an unstable notion in our cosmopolitan world, where half the Algerian team was born in France and half the French team was born in Algeria, as Breyten Breytenbach pointed out on a panel on the World Cup. “Our societies all over the world are far more complex and hybridized than they used to be,” he said. “A few years ago I saw an exhibit, Magiciens de la terre, at the Pompidou, and it was African artists doing African work, but many of them were actually living outside Africa, and some of them were even born outside Africa. The one point I’m trying to make is that while there has been far more movement from one continent to another, there is still something that endures. Why would someone of African descendance born in Britain define himself as an African artist, or an African soccer player?”

“My influences are transnational,” the Botswana poet TJ Dema said in an interview for the Festival and Co Gazette, a daily broadsheet circulated to catch festival-goers up on what they might have missed the previous day. “My generation has been accused of being heavily influenced by the American arts landscape, which is not wholly incorrect. But I feel you are a product of your environment. If you’re growing up not listening to your grandmother telling stories around the fireside, but instead in front of the television, and there are American people on that television, there is no way that isn’t going to be a part of your mindscape.”

“I’m a child of the universe,” she said. “Everywhere I go I pick and choose what I want to become part of my work.”

Except writers don’t play on teams

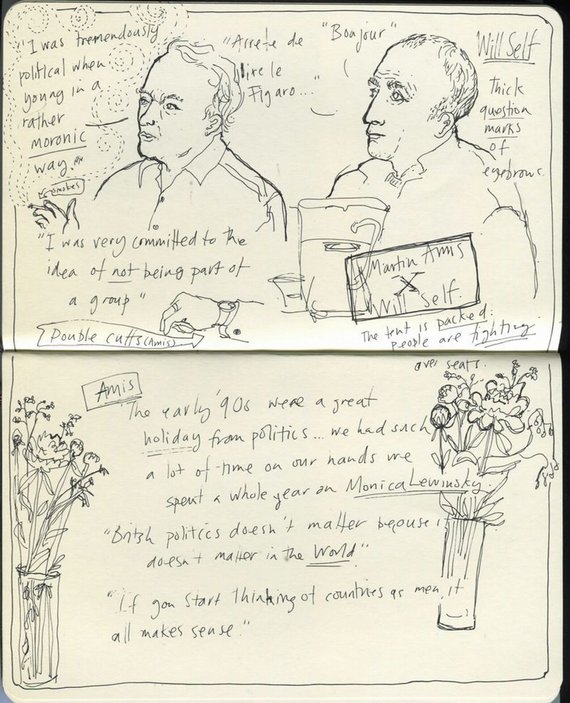

Repeatedly the writers at the festival sought to distance themselves from any kind of group identity. “I didn’t want to be a part of a communality,” Martin Amis said on foiling Christopher Hitchens’s attempts to get him to join the Trotskyists when they worked together at the New Statesman. “I was very committed to not being part of a group.”

The South African writer Njabulo Ndebele wore the yellow South African football jersey to his panel. “But I wouldn’t wear it at home,” he explained. “I have an inclination that when the crowd goes one way, I want to go another.”

Mark Gevisser, another South African writer, commented that one of the things that has struck him about the World Cup is the tension between the ways people are making their own national identities and they way they are decided for them — “how they choose to put a flag on their car — how you pimp your vehicle, by flying flags, or those funny little socks that people put on their rearview mirrors in South Africa, or those amazing hats that are a feature of South Africa football — and how on the other hand you might become subject to the flag that’s put in your hands by the leader. It seems they’re two different ways of belonging to a nation.” This idea was echoed throughout the festival by writers like Ian Jack, Nam Le, and Hanif Kureishi, who each discussed the complicated relationship they feel as writers to their own ethnic or national identities: “You don’t just play for one team,” someone might have said, but didn’t.

Sports bring people together, and can even help avoid civil wars, kind of like the rugby World Cup in that movie Invictus

Ndebele first spoke on a panel entitled “Biography as Political Storytelling in South Africa”; he read from his 2004 book The Cry of Winnie Mandela, which is an essayistic, fictionalized biography of the former first lady of South Africa — he explained that he chose to concentrate not on the drama of the relationship between the Mandelas, nor on their political moment, but on the everyday intimacy he imagines existed between them.

There is a subversiveness to writing about normality, he said; it “could be one of the most radical ways of fighting the system, because the system has to respond to complex individuals, rather than cardboard boxes.” But under apartheid, writing even about unspectacular things was “a very risky thing to do, because you could be accused of being blind to the suffering. […] reclaiming an experience of regular life. Even under apartheid, people still fell in love, they had uncles who visit.”

When asked about the possibilities of recuperating from apartheid, Ndebele evoked two great moments in South African sporting history: first, the 1995 Rugby World Cup, when Mandela appeared at the stadium wearing jersey number 6, the number of the team’s captain, Francois Pienaar. “Rugby was very much a white South African’s game, and for Mandela to actually stand there on that particular day was an extremely radical move, and of course, he made all those people who were in that stadium at that particular moment identify with him in a very special way.”

Second, Ndebele referred to a recent rugby match between Cape Town and Victoria, which couldn’t be held in the usual stadium because it’s currently occupied by the World Cup, and it worked out that the newly renovated stadium they were assigned to play in was in a mainly black area. “There was a lot of excitement about the fact that white South Africans — particularly the Afrikaaner kind — were going to play in a black township for the first time in a major game. Thousands of white fans went to see it. It was extraordinary, because for over the time of 80 or 90 minutes of the game, the fears that white South Africans had about black people (despite the fact that we’ve been all free since 1994) ceased operating. It was so good that many of them ended up having drinks afterward in [the neighborhood], in the places associated with violence and terror. Some of them forgot where they had parked their cars, and the locals took them to look for their cars. No one was molested, not a single car was stolen, and nothing disappeared, but the common memory was of a day of great fun an reconciliation.”

Ndebele stressed the fact that it is in the “unplanned interactions that in the end resonate much more deeply than political declarations. It is interesting that it is sporting events that do this, rather than the political rallies.”

Having the World Cup in South Africa promised redemption and recognition, kind of like the rugby World Cup in that movie Invictus, except this time for the entire African continent

Ndebele spoke again about this moment with Mandela the next day, on a panel with Breyten Breytenbach and Petina Gappah — “What the World Cup Means For Africa: Four Writers Kick the Ball Around.” The panel kicked off with Gappah’s son blowing the vuvuzela, and with a discussion of France’s shameful loss the previous evening, and Algeria’s win the evening before.

Mark Gevisser said that from what he had observed in the streets of Paris after the games, this dual defeat/win had prompted some feelings of rebellion amongst the Algerian population in France, that it provided at the very least “a moment of redemptive joy.”

“The possibility that the colonial masters are going to be sent home, and that Algeria and Ghana are going to make it to the next round on African soil I think is very exciting,” he said. “This world cup is not just about football. The former president, Thabo Mbeki, whose grand projet the World Cup was, said that it would be a moment when Africa would stand tall, and resolutely turn the tide of centuries of poverty and conflict.”

This seems a pretty tall order for a ball game, but we listen on:

“It has been called as important to Africa as the election of Obama was, and one of the most interesting moments of the last few days has been when the current president of South Africa Jacob Zulu went to wish the Bafana Bafana, which is the South African team, good luck (which didn’t do them any good), he was saying to them: bring home the cup, and he was very self-consciously imitating what Nelson Mandela did in 1995, with rugby, and as those of you who saw the Clint Eastwood movie know, that 1995 rugby cup was something of a redemptive moment when the Springboks, an all-white team, won the World Cup and South Africa was saved from civil war, because Nelson Mandela managed to seduce white Afrikaaners.

“And I think that the current World Cup holds a similar redemptive quality. Will this current World Cup do for South Africa and Africa economically, spiritually, psychologically, what the 1995 World Cup did?”

Ndebele and Gappah lamented the shortcomings of South Africa’s performance in the cup. Ndebele said this is linked to the social reality in South Africa, which is still being created. “Bafana Bafana,” on the other hand, “represent the story of South Africa, which is still in the process of being made.”

Petina Gappah confessed to being “a lot more pessimistic because the only reason the World Cup is being held in South Africa is because South Africa has become a brand — it’s something very specific, the rainbow nation, Mandela, and so on. I’m not sure that any other African country would have the same success of bidding for the World Cup. And so to me, the World Cup being held in South Africa is […] a story of South African’s inclusion in this moment of globalization. South Africa is part of the machine now, like it or not.” Gappah, being from Zimbabwe, lamented her own country’s exclusion, in spirit because of the human rights abuses of the country’s long-term leader, Robert Mugabe, and in practice because, well — they lost in the qualifying rounds.

Finally, Gappah concluded, if the World Cup will not ultimately do much for South Africa, much less the entirety of African, it is “because Bafana Bafana are not very good, they’re not the team that’s going to inspire South Africa and bring the country together in some kind of happy momentum.”

Sports are like books: they bring people together through a common idea… except no one ever said “the sporting industry is in crisis.”

André Schiffrin, Philip Pullman, and Olivier Postel-Vinay, editor-in-chief of the French magazine Books (yes that’s what it’s called in French, too) gathered for a panel led by Ian Jack called “Do Books Change Things? Are Things Changing Books?” Philip Pullman took the anti-technology stance, on the grounds that e-books and the Internet are not “self-sufficient, you can’t do them on your own. It depends on an enormous infrastructure that you can’t see in order to get it done at all.” You could make a book if you really wanted to, but it takes Amazon to make a Kindle.

“Books as books will survive until the last leaf of paper decays on the last book on the last shelf,” he asserted. “Books will decay, as do all human inventions, but the idea of the narrative of some length will last as long as human beings themselves do.”

Andre Schiffrin took a broader view. “There’s nothing wrong with the technology,” he said; it’s the way it limits what’s available to the reading public. “The problem is the conflict between form and content, there is the question of whether the new forms will change the content, and in what way.”

The changes in the publishing landscape, he said, “came more in the structure than in the technology — it changed by the fact of ownership, by the fact that large conglomerates recently bought up all the publishing and determined that it should be much more profitable than it had been, historically.”

“How can we afford to allow these monopolies to be established? Because of course once you have a monopoly, you can determine what’s going to be available, and a lot of what is being written will not be available on these machines. The idea that if you have a Kindle or an iPad you can get anything in the world is mythology. The books that are going to be available are the very same books that are on the bestseller list or the classics that can be had for free, but they’re not going to include the wide choice that you need. I say ‘need’ because in any democracy the ideas that come in books are an essential part of any debate.”

The point Shiffrin was making is that a bottom-line driven publishing industry means that the books that are most widely available are the ones with the most economic potential. Which, he argued, limits the field of options for readers; moreover, the conglomeration of the publishing houses leads to less editorial variety. Of course, more publishers would lead to more competition, but only if they’re each getting an equal shot at a share of the market; the larger publishers with more money have more of a chance at getting their books into things like the Kindle under the most favorable terms and onto the front tables of Barnes and Noble than a small independent publisher. A bottom-line oriented publishing industry ends up narrowing down the field, rather than becoming more inclusive; what readers want to read may not be available to them on their new electronic readers. It’s a little like if you’re a Zimbabawe fan but your team didn’t make it through the qualifying rounds so you have to content yourself with rooting for South Africa.

Countries are like people. Male people. But they should be run by female people. This idea = Amisian feminism

Countries are like people, Martin Amis proclaimed in his talk with Will Self, “and not very nice people. Very touchy, vain, obsessed by appearances, by face. There’s a tremendous anomaly in historiography, at least in Anglophone historiography, and that is countries used to be referred to as ‘she.’ [But] if we change it to ‘he’ then it all makes sense.the aggression, the unappeasable nature of state leaders is highly masculine.”

“Uh-oh,” the friend I came with said. “Here we go. Women are gentle, they are never violent…”

“I now am a millenarian feminist in that I believe what we have to evolve towards with some urgency is women heads of state who bring feminine qualities to government.”

At this, a few confused people applauded. “Stop clapping!” I hissed.

“The trouble with feminism as I see it now is that it’s founded on this idea that pole-dancing is empowering, and empowers women. What feminism has to do is not think that it’s emerging from Victorian values, it has to go back much further than that. Patriarchy [at this point I can’t understand what he said on my recorder as I am laughing too hard and a siren is going by]… for five million years. The idea that you could rise above that and really change things in a generation is an illusion. You’ve got to feel the weight of the past. But we have to be able to envisage a future — science has shown that there are certain basic differences between a male brain and a female brain; there are massive differences in acculturation, that women are kinder and gentler, and less close to violence than men, and this idea has to be reflected on the international scale.”

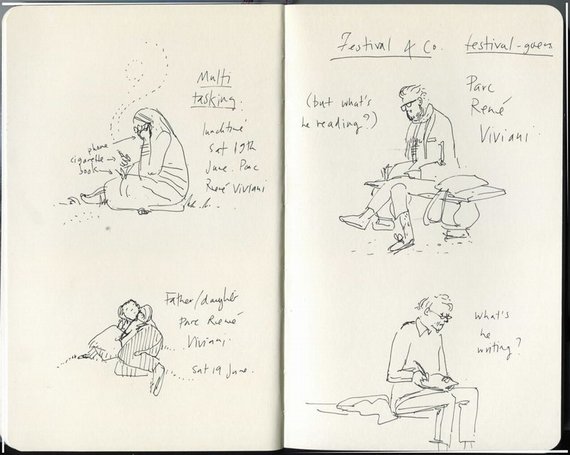

My friend the illustrator Joanna Walsh, who did all the drawings for the festival, sketched three journalists sitting in the front row grimacing. But the crowd is pleased. It has been told many funny jokes. And we all know what feminism really is — who cares if Amis has it a bit convoluted? We’re here to enjoy ourselves, not to theorize.

Still. For the rest of the festival Amis’s remarks were a touchstone of every conversation between female attendees.

While half the world goes nuts over a soccer ball, we sit under a tent talking about books.

Jeanette Winterson took the stage while the sound system blasted Pink’s single “Please Don’t Leave Me” and the audience — a full house spilling into the park on all sides — went nuts, as if they actually were at a rock concert.

She began. “So Europe’s in economic crisis, and the Third World is in poverty, the Middle East’s a warzone, the USA is dealing with political unrest and a huge environmental disaster, and China is set to become the world’s leading trade nation, and will do so at the expense of the environment. So the human race on planet Earth could easily manage a Gotterdammerung of a meltdown, and here we are, you me, at a literary festival. [Big laughs from the audience.] So. Are we crazy? What on earth have books and art got to do with the present state of the world? The money’s run out and nobody’s got time to do anything except survive! But Shakespeare and Company has got up a tent to celebrate books and ideas.”

The impact of the work of art, she maintained, is that it makes us “conscious and awake, frees up our own energy so that we can think clearly and feel honestly and act accordingly. There’s nothing passive about a work of art. And when we engage with it we throw off our own passivity. We realize that there’s always something that we can do, always someone that we can be, and we move, probably diagonally, like a chess piece, a little bit closer to being a human being, instead of a by-product of consumer culture.” She quoted Sontag’s Against Interpretation, reminding us that a work of art is not about something, it is something.

The impact of the work of art, she maintained, is that it makes us “conscious and awake, frees up our own energy so that we can think clearly and feel honestly and act accordingly. There’s nothing passive about a work of art. And when we engage with it we throw off our own passivity. We realize that there’s always something that we can do, always someone that we can be, and we move, probably diagonally, like a chess piece, a little bit closer to being a human being, instead of a by-product of consumer culture.” She quoted Sontag’s Against Interpretation, reminding us that a work of art is not about something, it is something.

“I believe that artists should be politically engaged,” she said. “This is our world, and we have to fight for our values. But if the only art that’s important is the art that deals directly with contemporary issues, then we could have no relationship with the art of the past. […]Art doesn’t have to struggle to be up to date with its subject matter. Because its real subject is humanity. Its territory is us, now, and in the past, and in the future. To remember Calvino’s first novel, it was a political novel. And after that he wanted to write very differently. And his friends in the Communist Party thought that he was betraying the cause. But he had the courage to honor his imagination, and that’s why we still read him. Because anyone who will follow their imagination helps the rest of us to follow ours.”

Where would a World Cup be without death threats?

Nigerian midfielder Sani Kaita received death threats on Sunday after receiving a red card, which led to his team’s loss to Greece.

Meanwhile here in Paris, there were rumors that Fatima Bhutto and Emma Larkin had both received death threats. For Bhutto, niece of Benazir, whose uncles, aunt, grandfather, and father were all assassinated, this is nothing new. She doesn’t even have a bodyguard; she tells the audience she doesn’t want one. Security is beefed up anyway.

Emma Larkin writes about Burma from inside Burma and apparently that isn’t allowed in Burma. She’s the only writer in the program not to have a sexy black and white author photo; instead there’s a photo of her book. Emma Larkin is an assumed name, too.

No one did any tailgating, but there was plenty of champagne

On Friday night after the last panel, over at the at the Refectoire des Cordeliers near Odéon, Paper Cinema presented their curious storytelling project: drawings projected onto a screen, wordless stories told to music. There are people actually moving the drawings around in front of a camera to create the story on the screen. Joanna is transfixed. But the music is foreboding and the drawings kind of macabre and freaky, so I don’t stay for it. There is food and champagne and lovely weather outside in the courtyard. I get so wrapped up in conversation out there I almost miss the Beth Orton concert which follows the freaky puppet show.[1]

Saturday night, we headed to the very exclusive private party at an hotel particulier in the 7th. Kristin Scott Thomas is there, in sky-high Louboutins. Jeanette Winterson wears a dress. All the big writers and big sponsors are here. We underlings are thrilled to be at this kind of event: everyone is nervous; everyone is on their best behavior. Some of us congregate outside in spite of the unseasonable chill.

“What is this place?” Nam Le asked, fresh off a plane from Italy, looking up at the house.

The girl who fetched him from the airport took this as a sign of Nam’s unfamiliarity with Parisian geography, and launched into an explanation. “Well you see if someone were to frown” — she frowned — “then the frown is the Seine, it goes like this, see?” and she began to point out all the monuments of Paris on her face. “So we’re here,” she said, indicating a point right under the middle of her frown.

“Oh,” Nam said. “I was actually wondering about the history of the mansion.”

Kristin Scott Thomas sat on the floor while Natalie Clein gave a transcendental cello performance; meanwhile the kids in the crowd passed around a piece of wood on which someone had painted the words “post-cello dance party!” Natalie eventually finished playing but no one danced.

11:30 rolled around and we were bodily kicked out of the space. We lingered in the courtyard until we were chased from there too. Half of us headed to an after-party at the flat of one of the people who work in the shop. The other half (my half) went home.

Sunday night was the closing party on the patio in front of the shop. There were piles of crushed lavender on the ground outside in front of the champagne station. It looked, and smelled, like an aromatherapy litter box. Storyteller Jack Lynch climbed up on a bench and launched into a story about a Scottish giant.

The party inside the shop was private, while the one on the patio was public. I was not aware of this until I wandered into the shop, where I had heard there was more champagne, and was stopped at the door and looked over. “You look familiar. You know someone or something. Come on in.” I went in and found various friends who also knew someone. We are a group of “know someones.” At least it’s a step up from “know nobodies.”

George Whitman, the 94 year-old founder of the bookshop, came down to the party around 9:30 and was given a special blue felt chair. His daughter Sylvia, who now runs the bookshop, sat with him for awhile, Tumbleweeds[2] gathering at their feet.

Dozens of people milled around until after midnight, while the staff closed up the shop for the night — they’re the only ones who are waiting for the party to end, as they have to have the shop open as usual at 11am the next day. The alcohol was finished and rumors of an extra bottle of champagne forgotten by Jeanette Winterson were dashed when the empty bottle was found in the green room, along with a couple of Tumbleweeds holding plastic cups of champagne in their hands, looking abashed, but happy.

Back | 1. To be fair this is one woman’s narrow-minded opinion. Everyone else really did love Paper Cinema.

Back | 2. Shakespeare and Company slang for the writers who stay at the shop for free in exchange for an hour of work per day (they have to read one book a day in addition to their bookselling duties).

[Image credits: Badaude]